Why is Jesus of Nazareth the most painted man of all time?

A journey through depictions of Christ in art... 🧵

A journey through depictions of Christ in art... 🧵

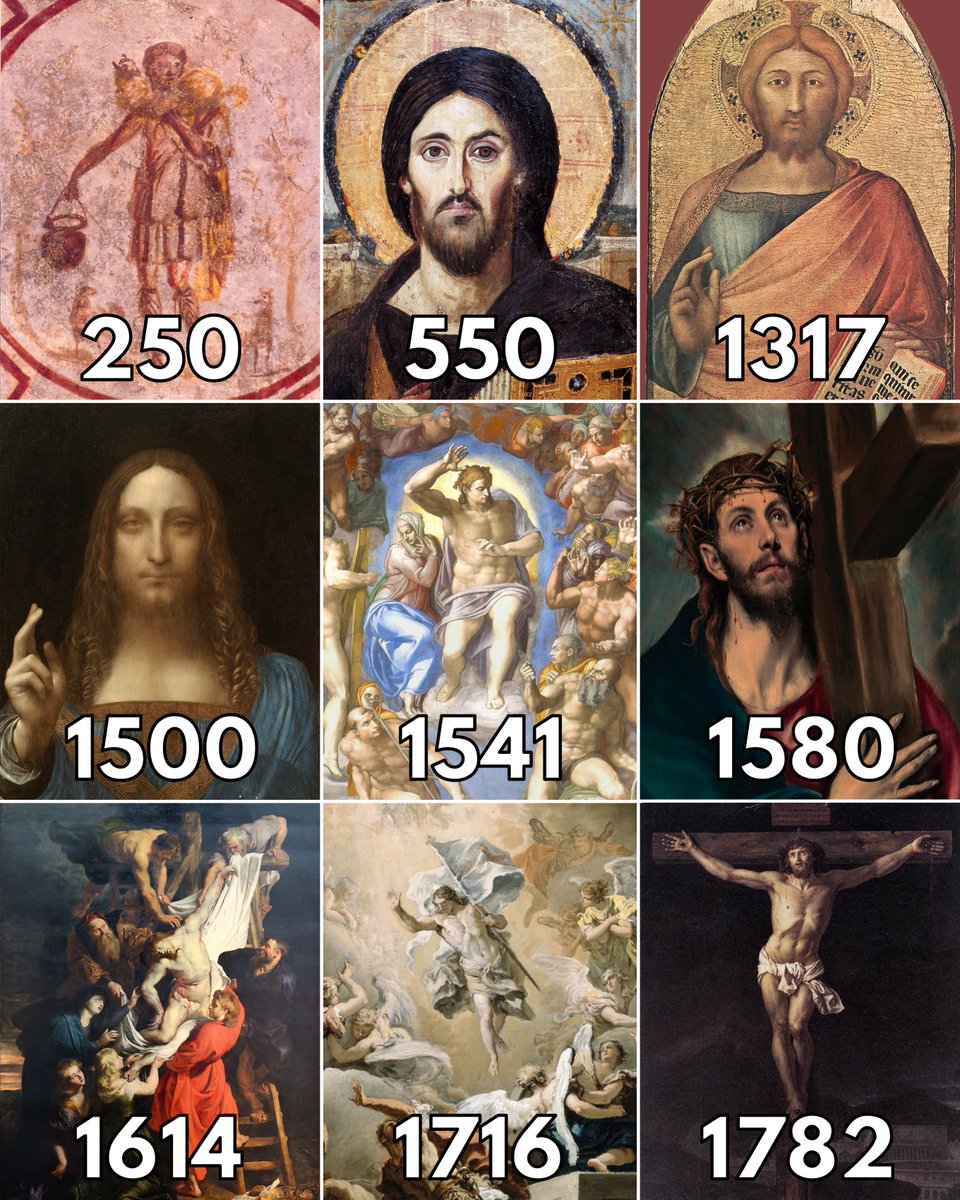

In Christianity's infancy, depictions of Jesus were scarce. Like other religions, early Christians were hesitant to be accused of idolatry.

Only once the Incarnation doctrine took hold, acknowledging that God had himself taken on finite, human form, did depictions flourish.

Only once the Incarnation doctrine took hold, acknowledging that God had himself taken on finite, human form, did depictions flourish.

Early icons like the Christ Pantocrator (right hand raised, Bible in the left) established his now-conventional appearance over time - bearded and long-haired.

One famous Byzantine example has lived in a small monastery on Mount Sinai since the 6th century:

One famous Byzantine example has lived in a small monastery on Mount Sinai since the 6th century:

The Church began to see art as a way to communicate the Gospel to illiterate congregations.

Catholic prelates across Europe advocated for the creation of art in all its forms, like this 12th century manuscript (Christ remained beardless for a few more centuries in the West):

Catholic prelates across Europe advocated for the creation of art in all its forms, like this 12th century manuscript (Christ remained beardless for a few more centuries in the West):

The Renaissance marked a major shift. Inspired by the lifelike accuracy of classical sculpture, artists like Leonardo Da Vinci pioneered a more naturalistic style.

Christ was shown not before golden backdrops, but grounded in human settings - like in The Last Supper (1498):

Christ was shown not before golden backdrops, but grounded in human settings - like in The Last Supper (1498):

But Michelangelo broke with pictorial tradition in The Last Judgment (1541).

He came under fire on several counts: painting Christ beardless, in a scene filled with nudity, mixing pagan mythology with Christian subject matter. He prioritized his artistic ambition over decorum.

He came under fire on several counts: painting Christ beardless, in a scene filled with nudity, mixing pagan mythology with Christian subject matter. He prioritized his artistic ambition over decorum.

A heightened emphasis on the naturalistic came with the Baroque era. Christ was now even more lifelike, with human expressions and deep emotion yielded by dramatic use of light and movement.

The Descent from the Cross by Peter Paul Rubens (1614):

The Descent from the Cross by Peter Paul Rubens (1614):

The Protestant Reformation came in the 16th century and objected to public religious images - many were destroyed.

Protestants eventually became more accepting of religious art, but it was smaller, usually confined to book illustrations, and rejected iconic elements like halos:

Protestants eventually became more accepting of religious art, but it was smaller, usually confined to book illustrations, and rejected iconic elements like halos:

After the 17th century, Christian art was produced in lesser quantities. But Biblical stories remained a key source of creative exploration for artists as art changed radically.

Rococo works showed him in bright, exuberant settings - The Resurrection by Sebastiano Ricci (1716):

Rococo works showed him in bright, exuberant settings - The Resurrection by Sebastiano Ricci (1716):

Then, the Neoclassical came back to the emphasis of his virtue and morality, with a more muted use of light and color.

Christ on the Cross by Jacques-Louis David (1782):

Christ on the Cross by Jacques-Louis David (1782):

Over the centuries, Jesus (often with Mary) became by far the most painted person in history.

Why? Sheer popular demand.

Once unleashed by the Church, religious art was desired for all uses - both mighty church altarpieces and personal works of devotion.

Why? Sheer popular demand.

Once unleashed by the Church, religious art was desired for all uses - both mighty church altarpieces and personal works of devotion.

And of course, Christian art benefited from the support of great patrons. Wealthy banking families are responsible for commissioning some of the greatest paintings in history, like Botticelli's Adoration of the Magi (1475):

Like the great churches that housed them, Christian artworks became vehicles of evangelization.

Just as the early Church fathers intended.

Just as the early Church fathers intended.

If you enjoy threads like these, you'll definitely enjoy this (free) weekly newsletter:

culturecritic.beehiiv.com/subscribe

culturecritic.beehiiv.com/subscribe

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh