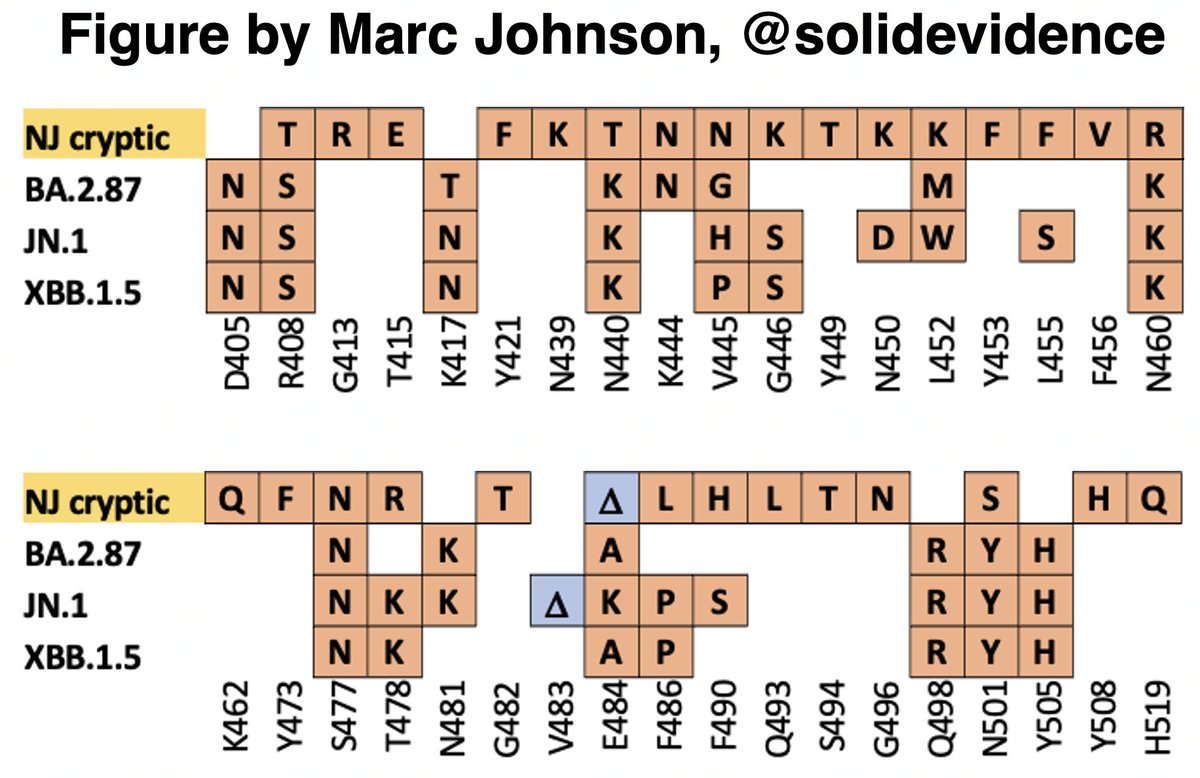

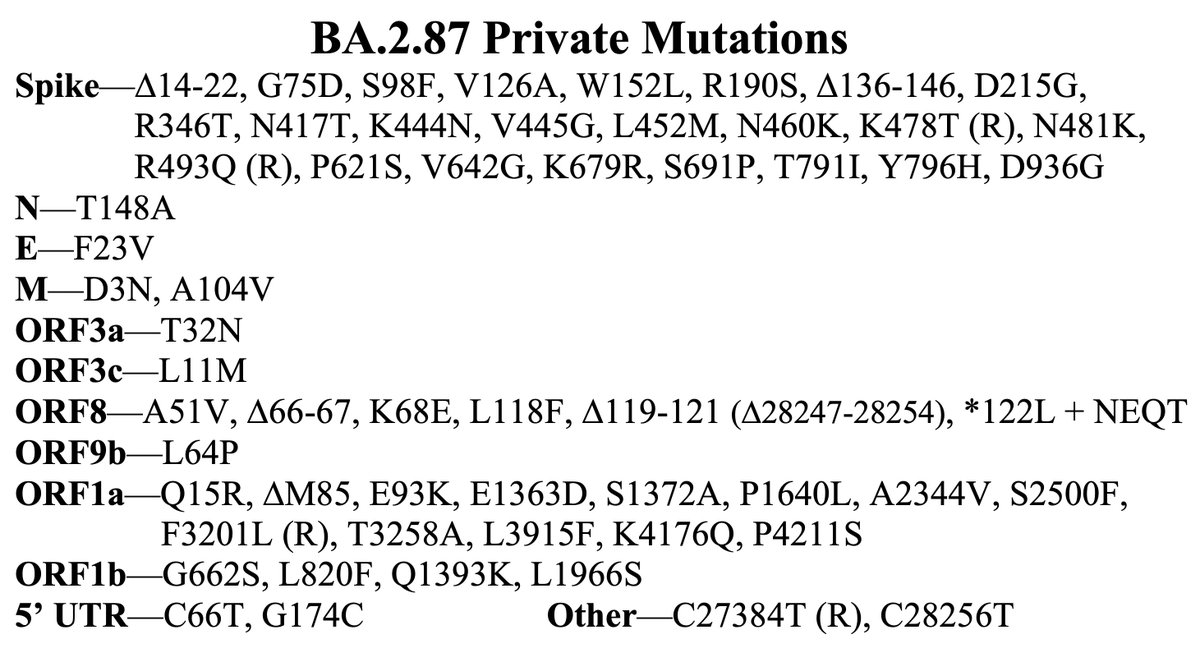

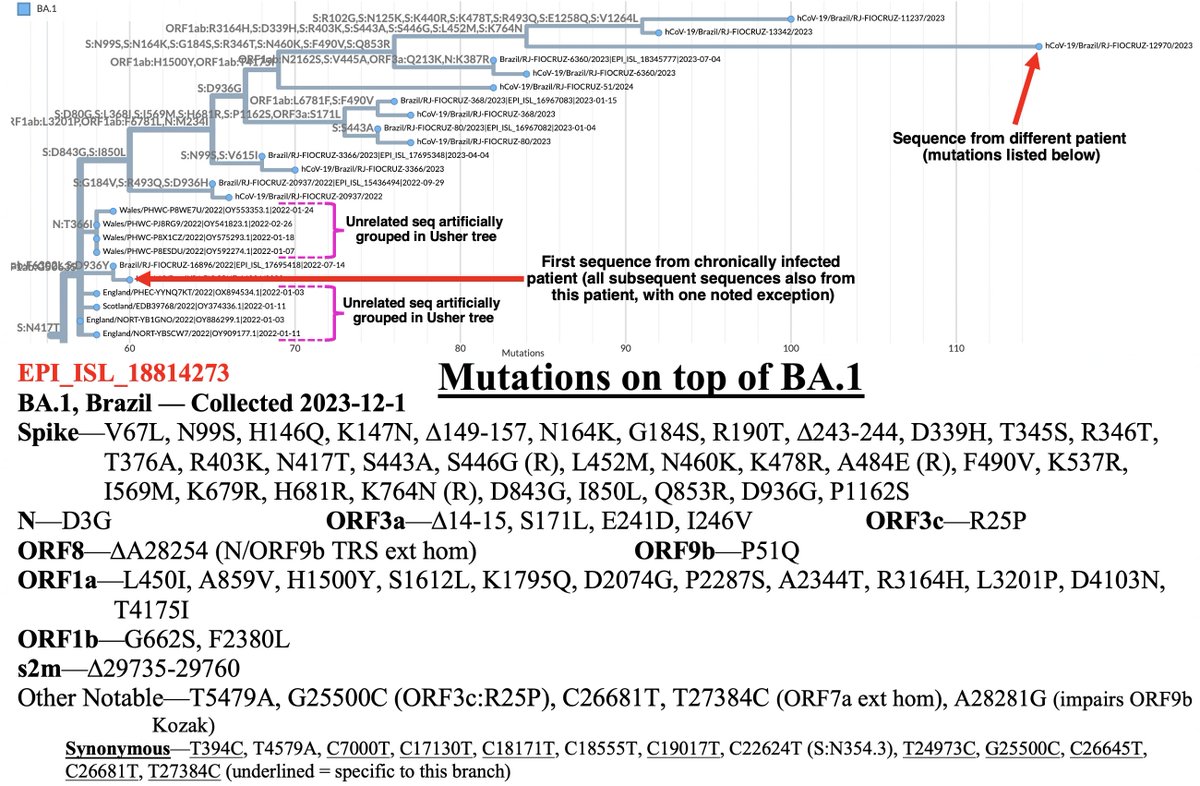

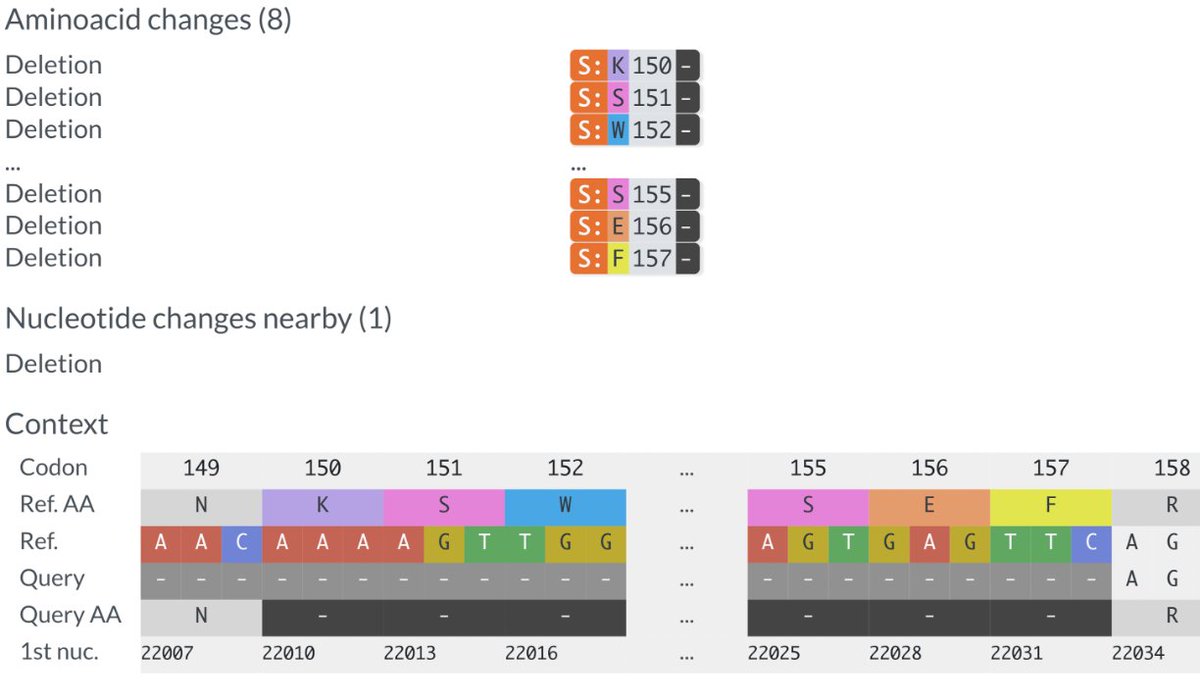

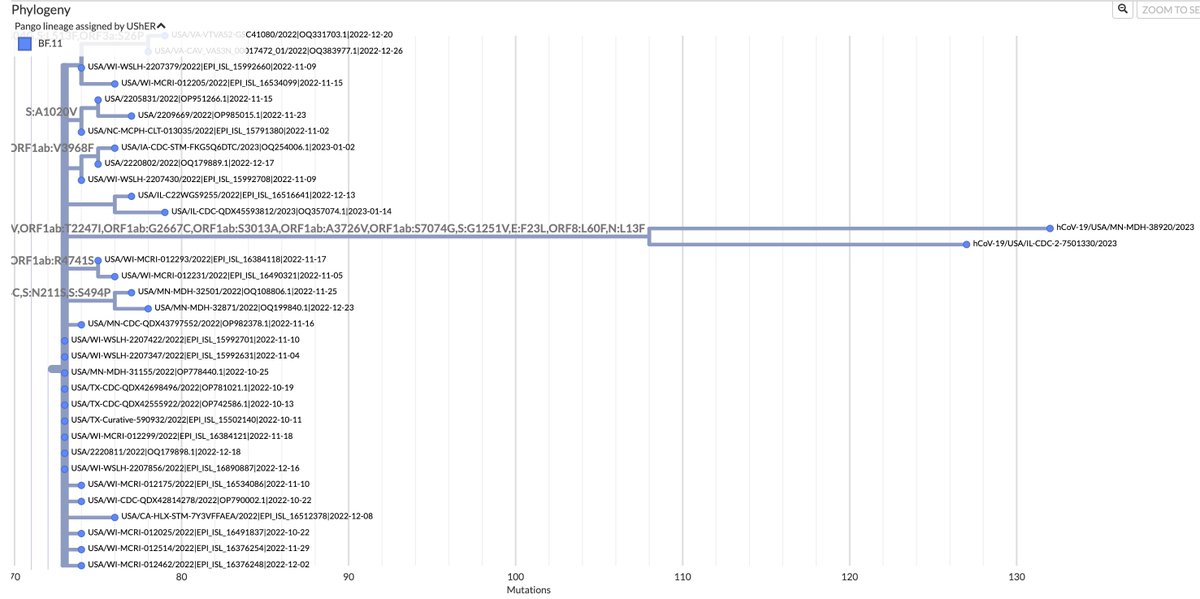

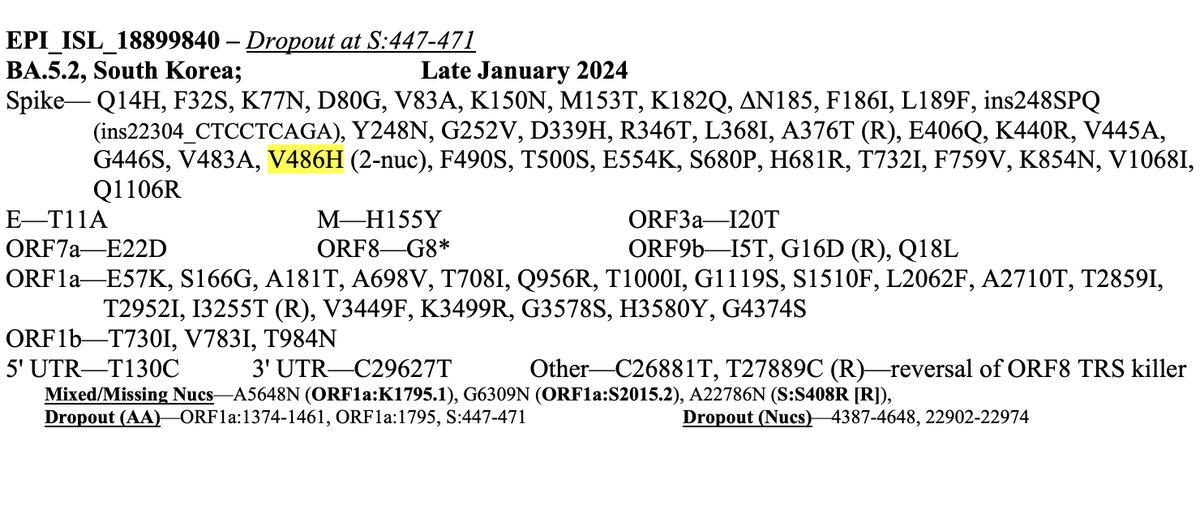

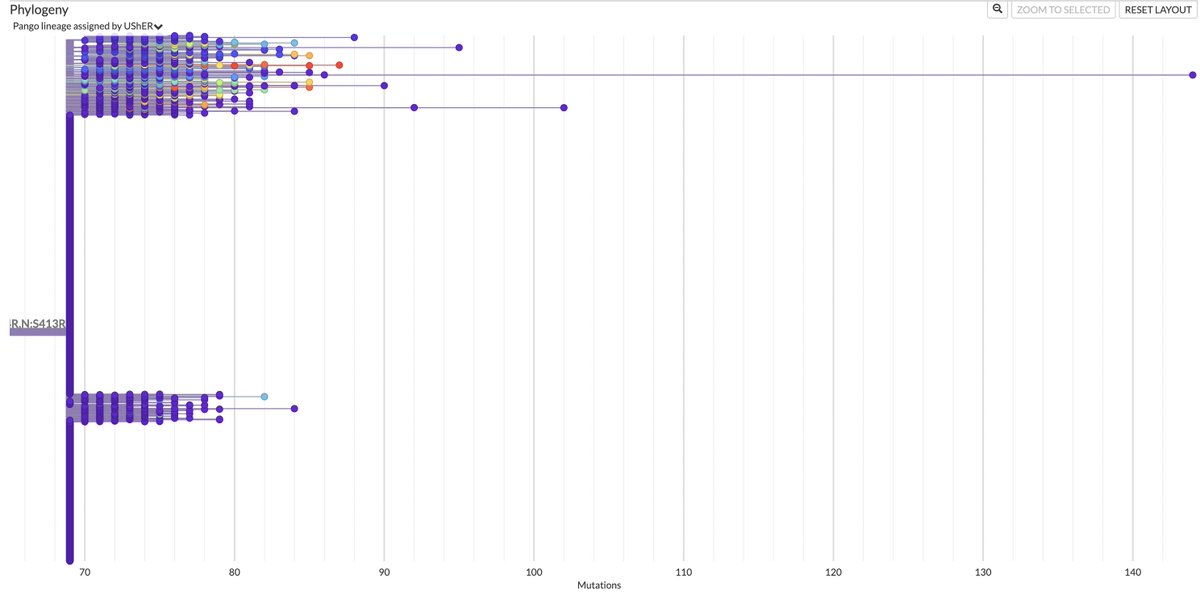

This could have the record for private spike mutations, surpassing even BA.1 & BA.2.86. ~35 spike AA mutations—& likely many others hiding behind dropout at S:447-471. Singlet in a country w/good surveillance, so unlikely to transmit. I'm super busy, so a few short remarks. 1/15

First, of the nucleotide mutations in amino acid (AA) coding regions, 61/71, or 85.9%, are non-synonymous, i.e. they cause a change in the AA. This is extraordinarily high and indicates strong positive selection—i.e. selection for advantageous mutations. 2/15

This sort of positive selection is a hallmark of chronic infections.

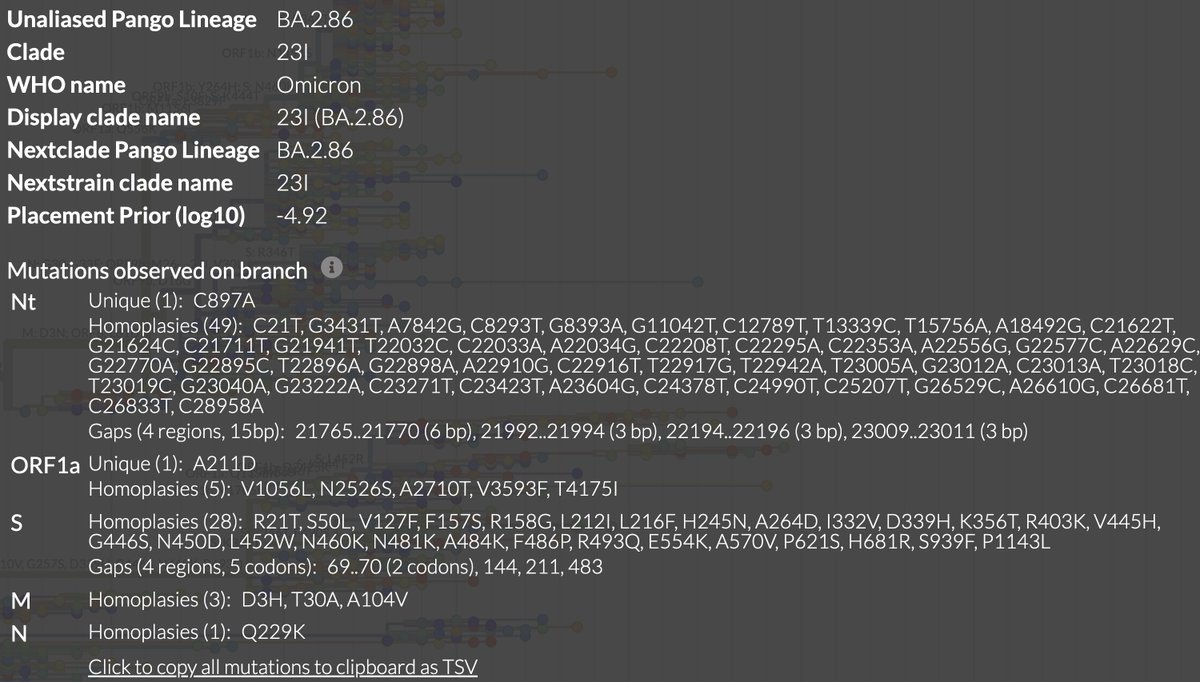

• Glycans—These are a type of sugar molecule that can hide exposed parts of the virus. S:F32S is somewhat convergent in chronics, & this is likely because it creates the N-X-[S/T] that can add a glycan. 3/15

• Glycans—These are a type of sugar molecule that can hide exposed parts of the virus. S:F32S is somewhat convergent in chronics, & this is likely because it creates the N-X-[S/T] that can add a glycan. 3/15

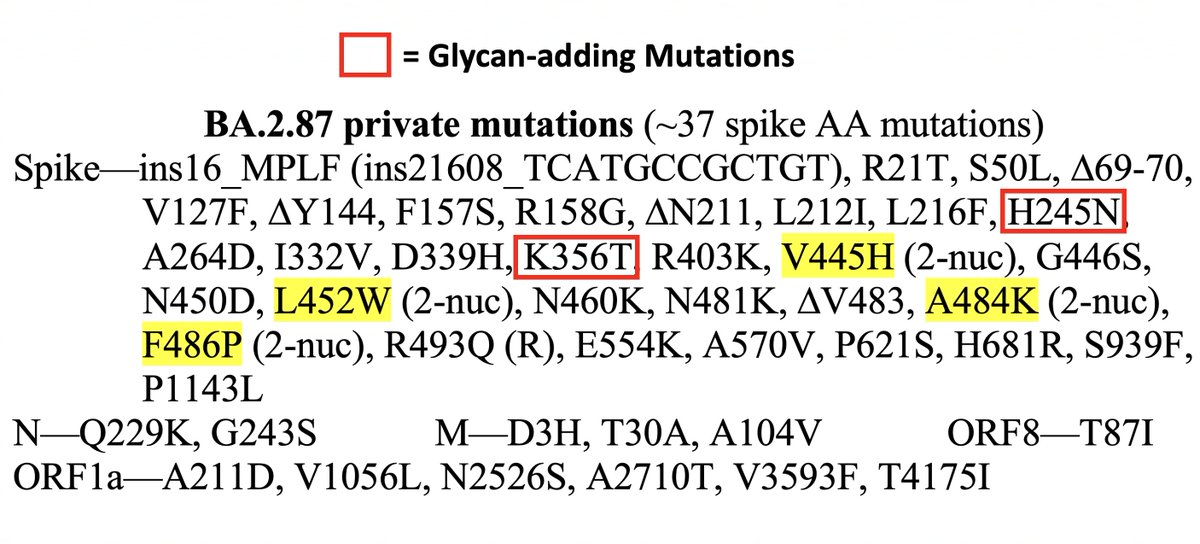

• Glycans (cont): S:Y248N also creates an N-X-[T/S] motif (where X is any AA but P) & so likely adds a glycan. We've seen Y248N before, notably in BA.2.76. BA.2.86 (JN.1 now) has S:H245N, which adds a glycan at a nearby N residue, as well as K356T—which also adds a glycan. 4/15

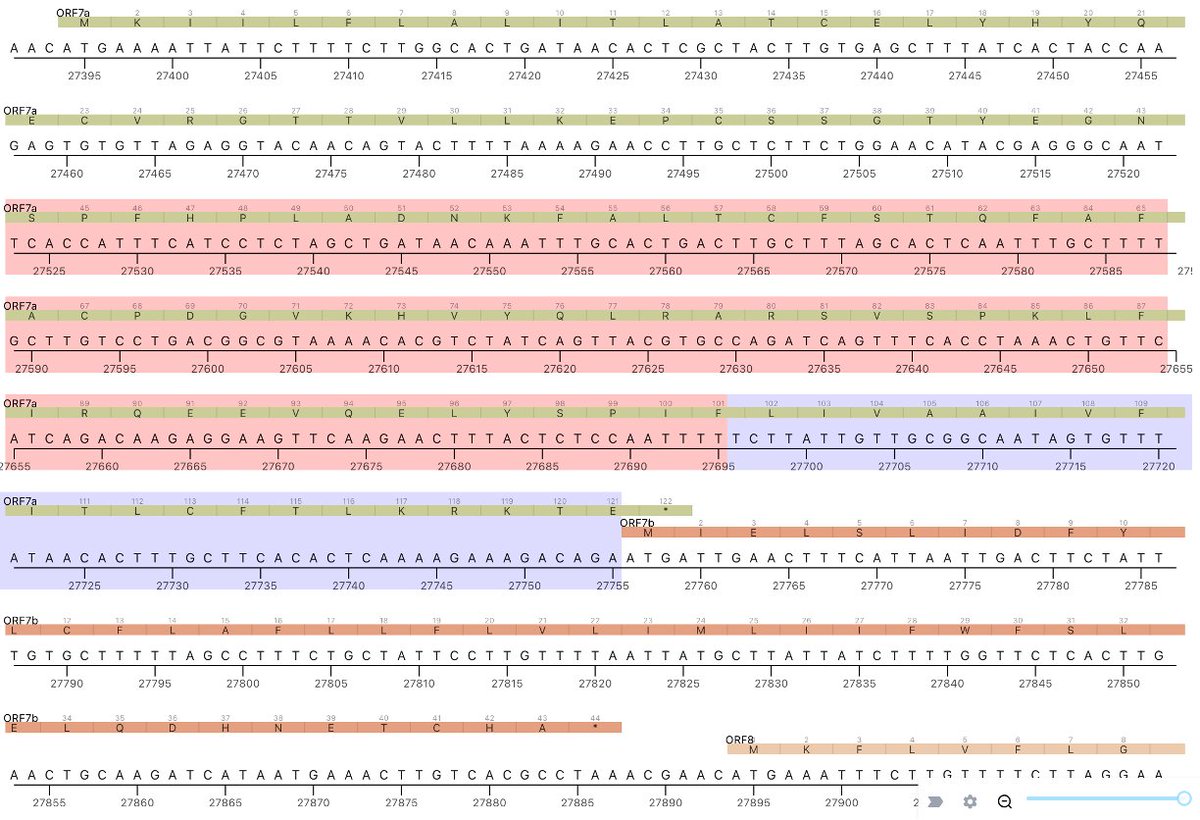

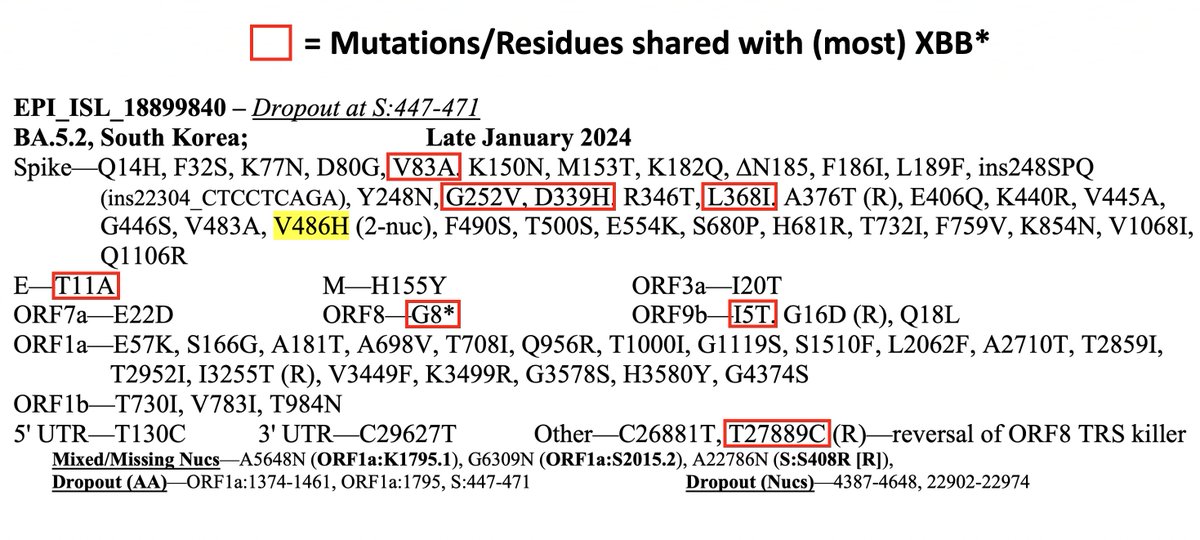

• XBB mutations—This seq shares an unusual number of mutations with XBB. Most are highly convergent in chronics & may have been added independently (S:D339H, S:L368I, E:T11A, ORF8:G8*, ORF9b:I5T). But others aren't so common (S:V83A, T27889C reversion). I'm not sure if... 5/15

...these resulted from a complex intrahost recombination process or were all acquired independently.

Normally, shared mutations w/another variant w/no clear breakpoint suggests a sequencing artifact, but there are too many chronic markers for this to be an artifact. 6/15

Normally, shared mutations w/another variant w/no clear breakpoint suggests a sequencing artifact, but there are too many chronic markers for this to be an artifact. 6/15

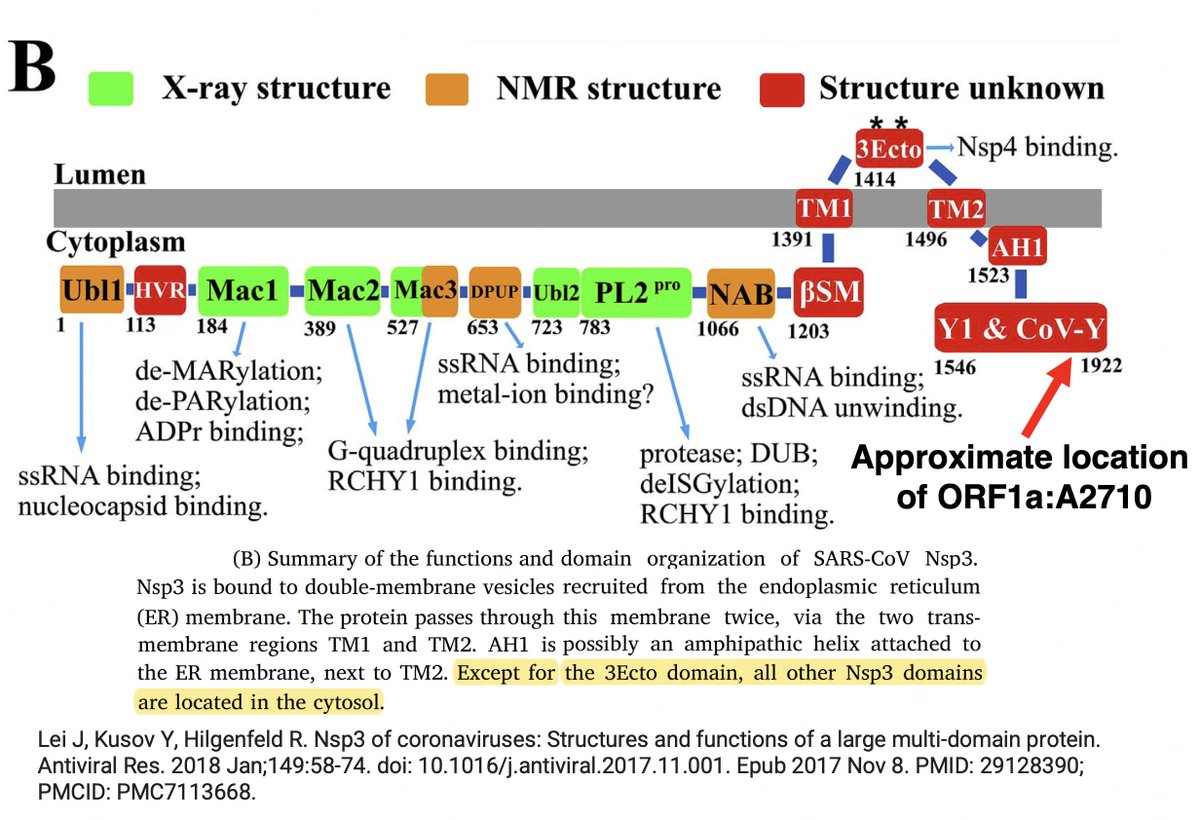

• ORF1a:A2710T—Also in BA.1 and BA.2.86. Outside those 2 lineages it's been extremely rare. Curiously, SARS-CoV-1 & most Bat-CoVs have ORF1a:2710S, a similar AA. Both form the glycan N-X-[S/T] pattern. However, most structures show this region of NSP3 region (NSP3_1892)... 7/15

...to be in the cytosol, in which glycans do not exist (as I understand it). Previously there had been predictions of >2 transmembrane regions of NSP3, but I do not know if those have been decisively refuted or not. 8/15

• C26881T—This is in BA.2.86 & is convergent in chronics. It was also in Epsilon (B.1.427/9) a variant that becomes more intriguing the more I learn about it.

It's synonymous, so it doesn't cause an AA change. What is it doing? I don't know. 9/15

It's synonymous, so it doesn't cause an AA change. What is it doing? I don't know. 9/15

Credit @shay_fleishon for calling attention to C26881T. C->T are by far the most common mut & are caused by a cell protein called APOBEC. But APOBEC favors certain nuc contexts. C26681T has an awful context & hence is less likely to occur by chance. 10/15

https://twitter.com/LongDesertTrain/status/1699196640534360358

C26881T could have something to do with the genome's secondary RNA structure, something I speculated about previously, but these things are poorly understood, so it's hard to come to any real conclusions on this front. 11/15

https://twitter.com/LongDesertTrain/status/1699196648130289685

• Unknown nucleotide at A5648 almost certainly forms ORF1a:K1795Q, perhaps the single most convergent mutation in chronic-infection sequences, as @SolidEvidence first pointed out.

And for once, we actually know what this mutation does. 12/15

And for once, we actually know what this mutation does. 12/15

https://twitter.com/SolidEvidence/status/1668995898943188995

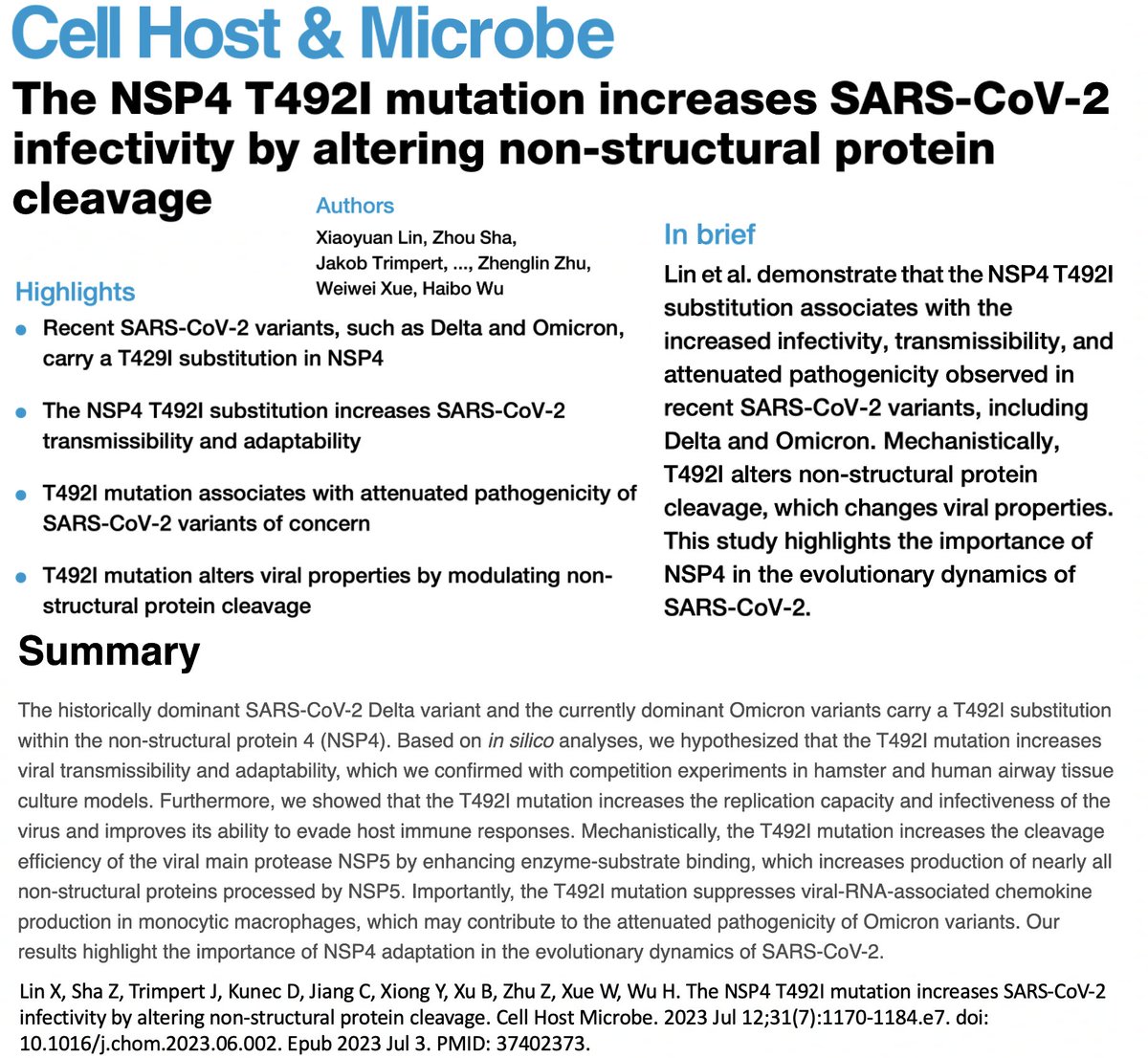

• ORF1a:I3255T (NSP4_I492T) reversion—Rare mutation but has shown up numerous highly mutated chronic-infection seqs. Any convergent reversion is undoubtedly purposeful. E.g., we know S:R493Q hugely increased ACE2 affinity. But most non-spike reversions remain mysterious. 13/15

One study found ORF1a:T3255I increases infectivity & immune evasion & reduces severity by improving the efficiency of NSP5 cleavage from the ORF1ab polyprotein. (All NSPs come in 1 big chunk & must be cut off to function properly.)

What purpose might its reversion serve? 14/15

What purpose might its reversion serve? 14/15

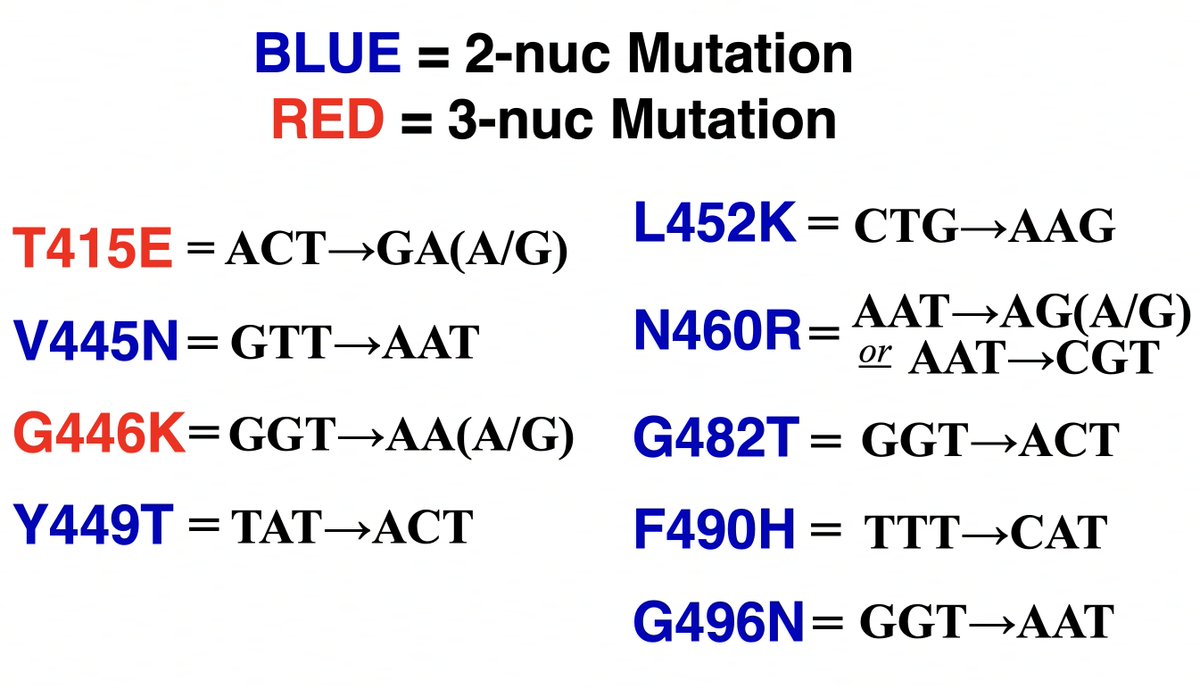

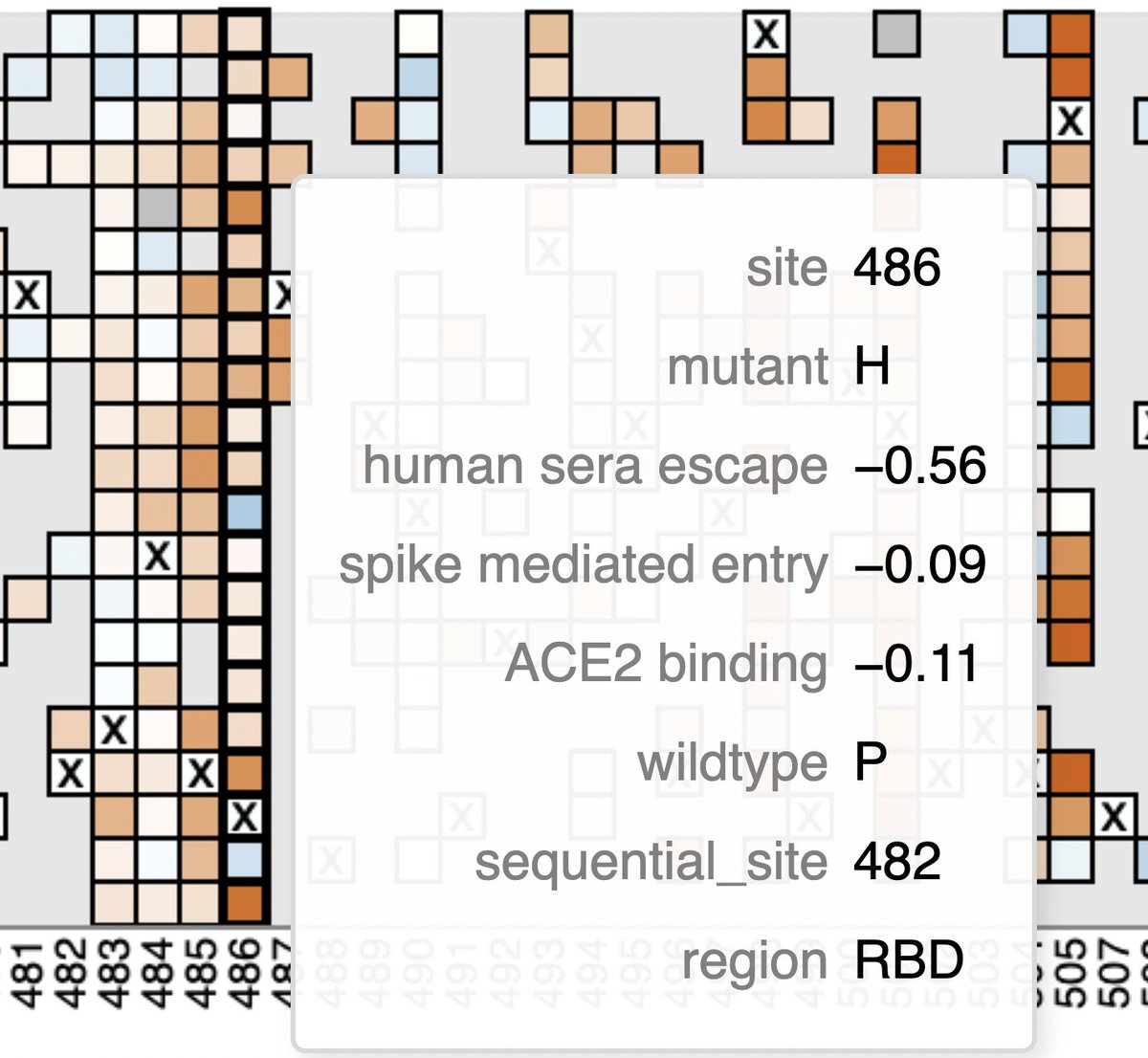

• S:V486H—Very rare 2-nuc mut. Looks un favorable on the @jbloom_lab/@bdadonaite spike-mutation tool in XBB background, but this spike is its own beast & it could act differently in this context.

I could go on forever, but I have too much else to do, so I'll end here. 15/15

I could go on forever, but I have too much else to do, so I'll end here. 15/15

One final note—S:F759V has only ever appeared in two previous sequences, making it (along with the insertion at S:248) the most distinctive mutation of all in this sequence.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh