Illuminated manuscripts embody the extraordinary union of beauty and knowledge.

Though the art of making them disappeared with the advent of the printing press, the most spectacular manuscripts survived the ages.

Here are 8 masterworks of medieval illumination🧵

Though the art of making them disappeared with the advent of the printing press, the most spectacular manuscripts survived the ages.

Here are 8 masterworks of medieval illumination🧵

1. The Morgan Crusader Bible, 13th century

Commissioned by French King Louis IX, the Morgan Crusader Bible depicts events from the Hebrew Bible set in the scenery and attire of 13th century France—it puts a medieval twist on Old Testament stories.

Commissioned by French King Louis IX, the Morgan Crusader Bible depicts events from the Hebrew Bible set in the scenery and attire of 13th century France—it puts a medieval twist on Old Testament stories.

Consisting of 46 folios, the manuscript displays illustrations accompanied by text written in either Latin, Persian, Arabic, or Hebrew. The vivid colors and attention to detail make it one of the most popular illuminated manuscripts.

2. The Black Hours, 15th century

The Black Hours is a book of hours (a type of prayer book) created in Bruges, Belgium. The style is in imitation of Wilhelm Vrelant, the most popular illuminator of the period, and constructed of vellum (calfskin) that’s been dyed pitch black.

The Black Hours is a book of hours (a type of prayer book) created in Bruges, Belgium. The style is in imitation of Wilhelm Vrelant, the most popular illuminator of the period, and constructed of vellum (calfskin) that’s been dyed pitch black.

Gold and blue paint overlay the dark background to create an almost otherworldly look. Written in silver and gold ink, the text lists the prayers to be said while depictions of Bible stories aid the reader in meditation.

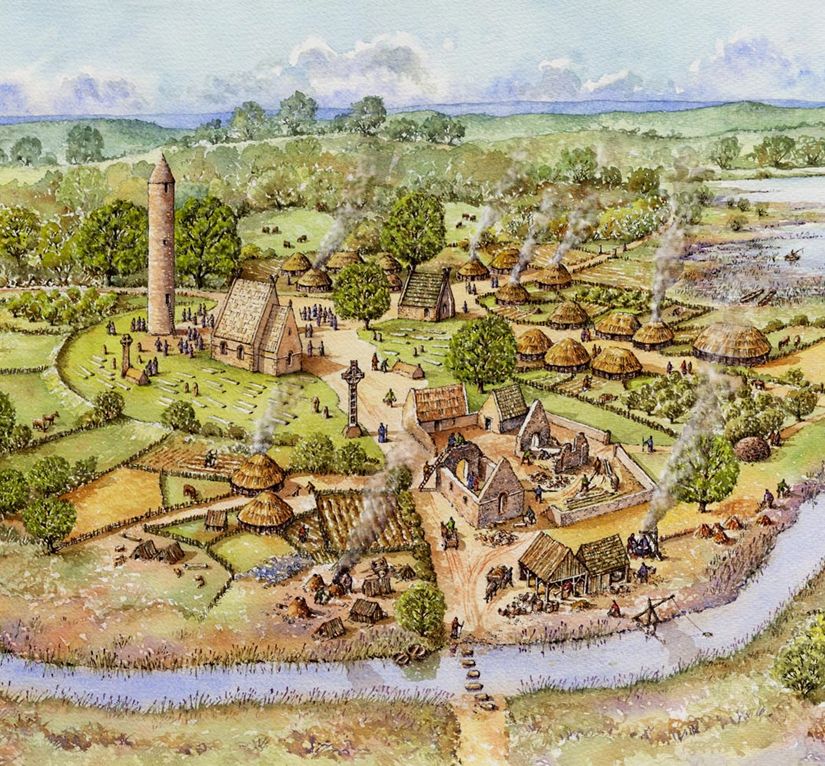

3. Book of Kells, 9th century

Among the most iconic medieval manuscripts is the Book of Kells. Created in a Columban monastery, the text is the pinnacle of early medieval calligraphy and illumination.

Among the most iconic medieval manuscripts is the Book of Kells. Created in a Columban monastery, the text is the pinnacle of early medieval calligraphy and illumination.

The graphics are a blend of insular art (the post-Roman era style of art popular in Irish monasteries) and traditional Christian iconography. Plants, animals, Celtic knots, and biblical figures decorate the 680 page volume to tell the story of Jesus’ life.

4. Codex Argenteus, 6th century

Latin for “Silver Book,” the Codex Argenteus contains the four gospels written in Gothic, making it one of the world’s foremost sources for the now-extinct language. The book was likely written as a gift for Ostrogothic king Theodoric the Great.

Latin for “Silver Book,” the Codex Argenteus contains the four gospels written in Gothic, making it one of the world’s foremost sources for the now-extinct language. The book was likely written as a gift for Ostrogothic king Theodoric the Great.

The work is particularly striking due to its purple-stained vellum pages, metallic ink, and silver binding. Looks almost Tolkienesque…

5. Acre Bible, 13th Century

Another work commissioned by Louis IX, the Acre Bible was compiled shortly after the king’s release from captivity during the disastrous 7th crusade. Upon returning to France, he deposited the masterwork in his newly built Sainte-Chapelle library.

Another work commissioned by Louis IX, the Acre Bible was compiled shortly after the king’s release from captivity during the disastrous 7th crusade. Upon returning to France, he deposited the masterwork in his newly built Sainte-Chapelle library.

It contains 19 books of the Old Testament, and its illustrations are considered masterpieces of crusader art.

6. The Aberdeen Bestiary, 12-13th century

A bestiary is essentially an encyclopedia of animals and mythical beasts. They gained popularity throughout the Middle Ages as readers could learn about exotic animals or mythical creatures.

A bestiary is essentially an encyclopedia of animals and mythical beasts. They gained popularity throughout the Middle Ages as readers could learn about exotic animals or mythical creatures.

This one was owned by Henry VIII, and features a retelling of the Genesis creation story with fantastical images of creatures both real and imagined.

7. The Very Rich Hours of the Duke of Berry, 15th century

The best surviving example of the International Gothic style of illumination, it’s one of the most lavishly designed late-medieval manuscripts and contains well over 100 illustrations.

The best surviving example of the International Gothic style of illumination, it’s one of the most lavishly designed late-medieval manuscripts and contains well over 100 illustrations.

8. The Berthold Sacramentary, 13th century

Commissioned by the abbot of Weingarten Abbey, this manuscript is a form of missal called a sacramentary used by priests for liturgical services.

Commissioned by the abbot of Weingarten Abbey, this manuscript is a form of missal called a sacramentary used by priests for liturgical services.

A sacramentary gives the priest's readings and prayers for the Mass. This one is a paragon of Romanesque art.

If you enjoyed this thread, kindly repost the first post, linked below:

https://x.com/thinkingwest/status/1759300518411657426?s=20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh