UPDATE:

Last week, a Nepali doctor filed a class action lawsuit against the National Board of Medical Examiners, alleging discrimination based upon national origin and requesting that invalidated USMLE scores be restored while examinees appeal.

Today, the NBME responded.

(🧵)

Last week, a Nepali doctor filed a class action lawsuit against the National Board of Medical Examiners, alleging discrimination based upon national origin and requesting that invalidated USMLE scores be restored while examinees appeal.

Today, the NBME responded.

(🧵)

https://twitter.com/jbcarmody/status/1757965502968672748

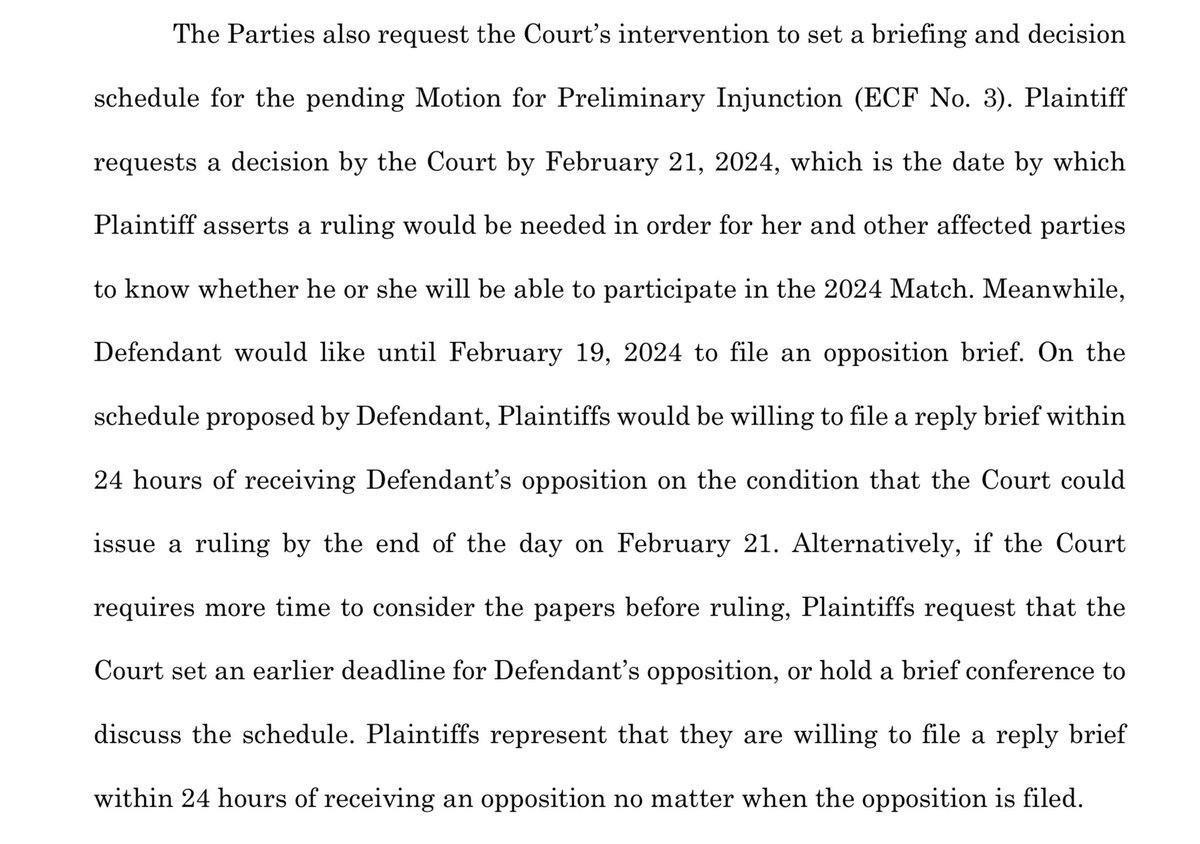

The court will issue a ruling by February 21 - so the outcome of the suit remains uncertain.

Still, the NBME’s filing provides additional details on the scope of the scandal, how the cheaters were caught, and what’s likely to happen in the future.

Still, the NBME’s filing provides additional details on the scope of the scandal, how the cheaters were caught, and what’s likely to happen in the future.

First, the NBME confirmed the number of examinees involved.

According to their filing, 832 examinees have had at least one of their USMLE scores invalidated… so far.

According to their filing, 832 examinees have had at least one of their USMLE scores invalidated… so far.

Second, the NBME confirmed that they found the cheaters not through any kind of routine monitoring for suspicious patterns, but only after receiving tips about cheating.

How did the cheating ring work?

Students who could show “a nexus to Nepal and a USMLE testing permit” were admitted to a Telegram group called “Arahmba.”

So once they became aware of it, “an individual acting on behalf of the USMLE” infiltrated the group.

Students who could show “a nexus to Nepal and a USMLE testing permit” were admitted to a Telegram group called “Arahmba.”

So once they became aware of it, “an individual acting on behalf of the USMLE” infiltrated the group.

The NBME also clarifies how they established that individual examinees cheated.

They used agreement analysis, examining the specific pattern of right - and wrong - answers chosen by examinees.

They used agreement analysis, examining the specific pattern of right - and wrong - answers chosen by examinees.

(If you watched my videos in the immediate aftermath of the scandal, I predicted this - start listening around 7:50 or so.)

MORE Emergency Mailbag: The USMLE Cheating Scandal, Part II

MORE Emergency Mailbag: The USMLE Cheating Scandal, Part II

They also identified cheaters by their very unusual response times and accuracy.

For instance, although USMLE questions typically require ~90 seconds to answer, the plaintiff answered many USMLE Step 1 questions in <20 seconds - and did so with 100% accuracy.

For instance, although USMLE questions typically require ~90 seconds to answer, the plaintiff answered many USMLE Step 1 questions in <20 seconds - and did so with 100% accuracy.

The NBME provided some screenshots from the Telegram group’s ringleaders admonishing users not to attract attention by finishing the USMLE too early.

(Here, “PQ” = previous questions.)

(Here, “PQ” = previous questions.)

The NBME also provided some explanation for why they singled out Nepal for their initial investigation.

Last year, examinees from Nepali medical schools scored significantly higher than those from ANY other country - including the United States.

Last year, examinees from Nepali medical schools scored significantly higher than those from ANY other country - including the United States.

The NBME also pointed out how, even as the average examinee from Nepal was scoring 259 on Step 2 CK, the number of USMLE test-takers from Nepal was increasing almost exponentially.

Previously, I compared this dramatic change and ridiculously high performance to the steroid era in baseball. (Start around 16:50 if you’re in the mood for an extended analogy.)

MORE Emergency Mailbag: The USMLE Cheating Scandal, Part II

MORE Emergency Mailbag: The USMLE Cheating Scandal, Part II

The plaintiff’s attorneys have nonetheless seized on the NBME’s focus on Nepal as impermissible under the Civil Rights Act, comparing it to racist policies like “stop and frisk.”

However, the most intriguing acknowledgement is that the USMLE isn’t only investigating Nepal.

In fact, using agreement analysis, they’ve **already found evidence of cheating** in examinees who took the USMLE in Jordan, Pakistan, and India.

Look for the other shoe to drop soon.

In fact, using agreement analysis, they’ve **already found evidence of cheating** in examinees who took the USMLE in Jordan, Pakistan, and India.

Look for the other shoe to drop soon.

However, the USMLE’s process isn’t especially rapid.

The first tips mentioned in the lawsuit were received in January 2023 - so it took over a year for them to invalidate anyone’s scores.

The first tips mentioned in the lawsuit were received in January 2023 - so it took over a year for them to invalidate anyone’s scores.

The court should announce its decision in the next couple of days, and when it does, I’ll add another update.

Stay tuned.

/end

Stay tuned.

/end

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh