Art Deco is the incarnation of civilizational energy—the spirit of Achilles and Tesla in architectural form.

The ultimate style for high civilization...

The ultimate style for high civilization...

Kenneth Clarke said:

“Vigour, energy, vitality: all the civilizations—or civilizing epochs—have had a weight of energy behind them.”

Art Deco embodies this vitality.

“Vigour, energy, vitality: all the civilizations—or civilizing epochs—have had a weight of energy behind them.”

Art Deco embodies this vitality.

He claimed civilization had 3 enemies:

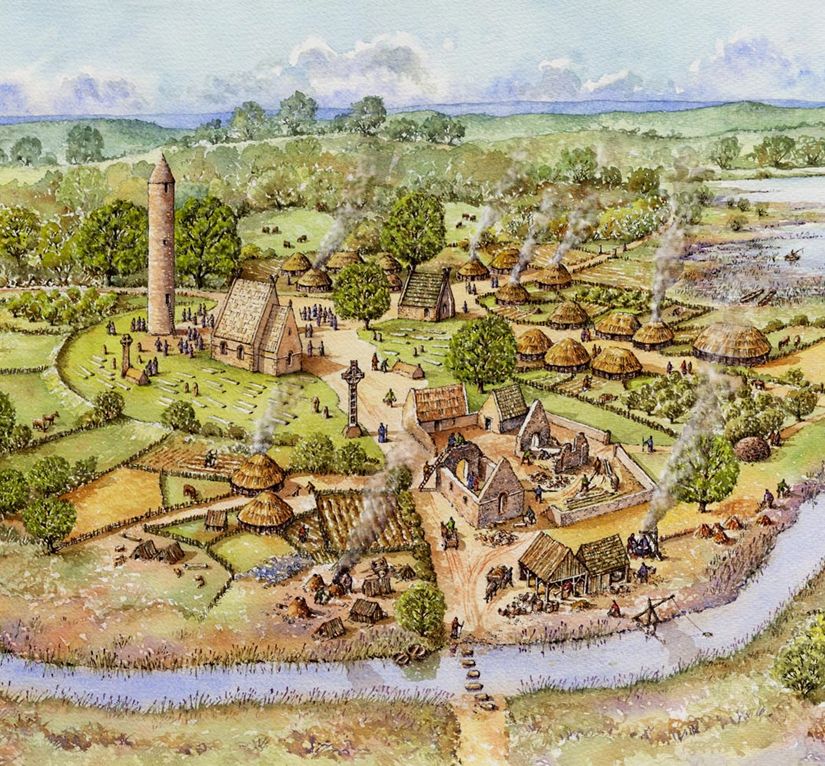

"First of all fear — fear of war, fear of invasion, fear of plague and famine, that make it simply not worthwhile constructing things, or planting trees or even planning next year’s crops."

Does this look fearful to you?

"First of all fear — fear of war, fear of invasion, fear of plague and famine, that make it simply not worthwhile constructing things, or planting trees or even planning next year’s crops."

Does this look fearful to you?

Art Deco often features exotic materials, such as ebony and ivory, and exquisite craftsmanship.

The fruits of a culture unafraid to try new things.

The fruits of a culture unafraid to try new things.

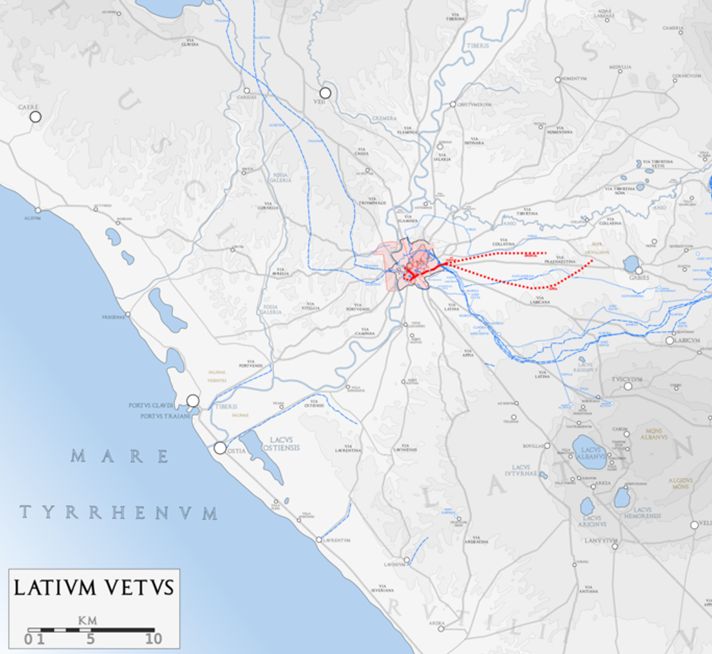

The next enemy is a lack of self-confidence. A culture regrets its past, stifling its ability to progress.

Art Deco's blocky, muscular designs show a civilization secure yet determined. Its aura is simultaneously ancient and futuristic.

A timeless spirit of crushing grandeur.

Art Deco's blocky, muscular designs show a civilization secure yet determined. Its aura is simultaneously ancient and futuristic.

A timeless spirit of crushing grandeur.

So many Art Deco designs look like they could be 5,000 years old. It's an artistic style that appreciates a civilization's past.

Finally Clarke warns against exhaustion:

"the feeling of hopelessness which can overtake people even with a high degree of material prosperity."

Art Deco's imagery is all about vitalism. God-like men, exalted maidens, mythical beasts—dreams of a civilization with a vision.

"the feeling of hopelessness which can overtake people even with a high degree of material prosperity."

Art Deco's imagery is all about vitalism. God-like men, exalted maidens, mythical beasts—dreams of a civilization with a vision.

Art Deco embodies faith in social and technological progress.

It fosters a belief that the best is yet to come.

It fosters a belief that the best is yet to come.

We need to be Art-Deco-maxing as a civilization.

It's the architectural style of a people who've triumphed—and aren't done yet.

It's the architectural style of a people who've triumphed—and aren't done yet.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh