Early Christians used the Greek concept of metanoia to describe the inner transformation people underwent while converting.

But hearts and minds weren't all the religion changed. Pagan temples and holy sites were radically transformed in a process called Christianization🧵

But hearts and minds weren't all the religion changed. Pagan temples and holy sites were radically transformed in a process called Christianization🧵

In the early centuries after Christ, Christianity rapidly expanded throughout the Roman empire. Paganism receded leaving temples unused and decrepit. Finally, Theodosius I closed them by decree at the end of the 4th century.

Christ had conquered Rome

Christ had conquered Rome

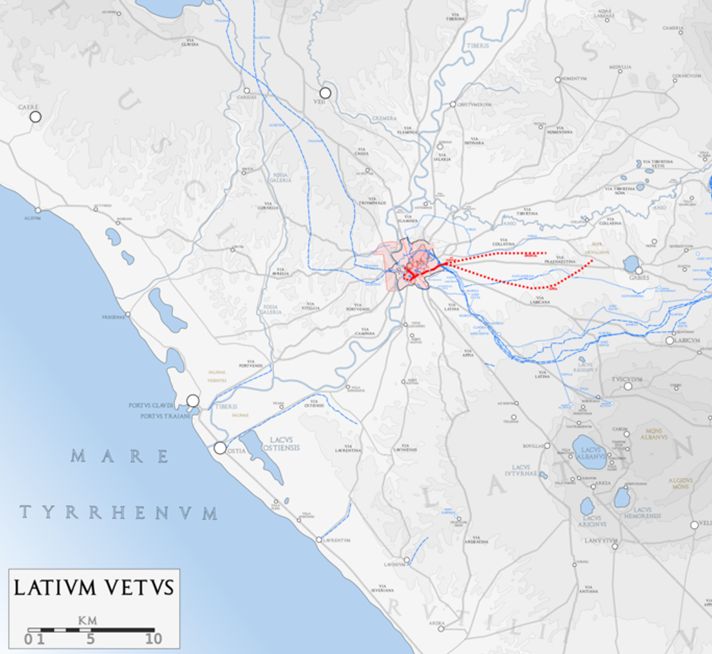

Though Christians often chose locations of martyrs’ deaths for their churches like "Saint Paul Outside the Walls," the empty temples of Rome’s defeated pantheon were prime real estate for prospective church builders.

Christians Initially shunned them because of their pagan ties, but eventually convenience won the day. It was easier to use existing buildings than construct new ones.

After all, Christianity was founded on the idea of resurrection—why couldn't this apply to buildings too?

After all, Christianity was founded on the idea of resurrection—why couldn't this apply to buildings too?

The most pronounced example of Christianization remains the Pantheon in Rome. Once housing idols to multiple Roman gods, the massive building was converted into a church called St. Mary and the Martyrs in 609 by Pope Boniface IV.

The pope declared a triumph over demonic forces:

“...the commemoration of the saints would take place henceforth where not gods but demons were formerly worshiped.”

“...the commemoration of the saints would take place henceforth where not gods but demons were formerly worshiped.”

After purifying the temple of any pagan artifacts, twenty-eight cartloads of martyrs’ relics were taken from the catacombs and placed under the altar—an instantiation of the concept that victory came through death in Christ.

Around the same time, the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina also became a church. Now called San Lorenzo in Miranda, the current 11th century structure is encased in the shell of the former pagan temple.

Greek temples were also converted. In Syracuse, the Temple of Athena was made into a cathedral by Bishop Zosimo in the 7th century. The original Doric columns are still visible and now support the structure of the cathedral.

The most famous Athenian temple, the Parthenon, was remodeled into a church at one point in the early 6th-century. It became the Church of the Theotokos, donning Christian iconography until the 15th century when the Ottomans conquered the area.

Like temples, administrative buildings were Christianized. Roman basilicas, which usually housed courts of law, were ideal prospects for Christian churches due to their size and shape.

It's why some churches are called “basilicas” even today.

It's why some churches are called “basilicas” even today.

The Roman senate house, the Curia Iulia, was transformed into Sant 'Adriano al Foro in 630 by Pope Honorius I. Its conversion served as a profound reminder of the power which now controlled Rome.

Greek and Roman buildings weren’t the only ones that were Christianized. At Montmartre, the church of Saint Pierre was established by Saint Denis atop a mercurii monte—a “high place” dedicated to Lugus, a major Celtic deity.

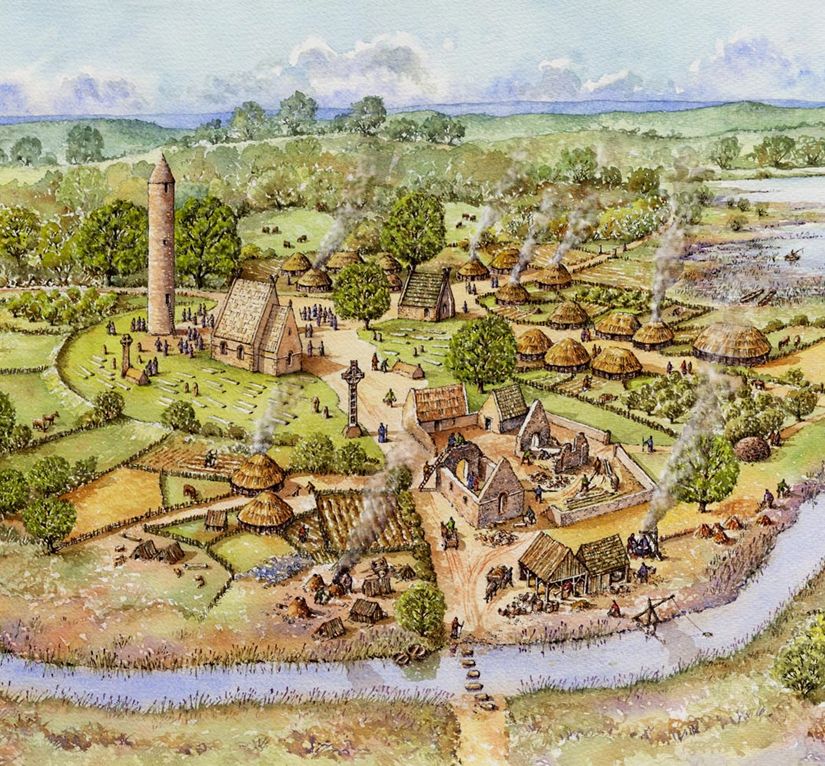

In northern Europe and Britain, crosses adorning menhirs (bronze age standing stones) or churches atop Neolithic burial mounds are not an uncommon sight.

Christians staked their claim over any reminder of an area's pagan past.

Christians staked their claim over any reminder of an area's pagan past.

A letter from Pope Gregory I to a priest in Britain at the start of the 7th century reveals that the conversion—rather than destruction—of existing pagan sites may have been a strategy to ease the transition from paganism to Christianity for the inhabitants of the region.

Pope Gregory wrote:

“the shrines of idols amongst that people should be destroyed as little as possible…in knowledge and adoration of the true God [the people] may gather at their accustomed places more readily.”

“the shrines of idols amongst that people should be destroyed as little as possible…in knowledge and adoration of the true God [the people] may gather at their accustomed places more readily.”

In the 16th century, Christianization continued in the New World. The Templo Mayor, the spiritual focal point of Tenochtitlan, was destroyed during the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs. The Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral now stands upon its rubble.

The Christianization of the pagan world displays Christians’ intent to transform not only souls, but the physical world as well. They were intent on building a ‘new creation’ from the remains of the old world, transfiguring the very earth and stone into conduits of the divine.

If you enjoyed this thread and would like to join the mission of promoting the beauty and goodness of the Western tradition, kindly repost the first post (linked below) and consider following: @thinkingwest

https://x.com/thinkingwest/status/1765764354710905011?s=20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh