Some thoughts on Q 9:30, which asserts that “Jews say ‘ʿUzayr [?] is the son of God’ & Christians say ‘Christ is the son of God’.”

Most scholars take ʿUzayr to be Ezra, but he is not known as a son of God in the Jewish tradition.

Can the noun refer to the Jewish Messiah?

1/11

Most scholars take ʿUzayr to be Ezra, but he is not known as a son of God in the Jewish tradition.

Can the noun refer to the Jewish Messiah?

1/11

This idea occurred to me last year in the light of Q 5:78, which claims: “the unbelievers from the Children of Israel were cursed on the tongue of 𝗗𝗮𝘃𝗶𝗱 and Jesus son of Mary.”

Why David?

An earlier verse that denounces those who divinized Jesus may furnish a clue.

2/11

Why David?

An earlier verse that denounces those who divinized Jesus may furnish a clue.

2/11

Jesus came to be considered the son of God or/and God partly because he was identified with the Davidic Messiah/King, who is described as the son of God or as divine in some biblical texts.

3/11

3/11

So, perhaps Q 5:78 mentions David to claim that he rejected those who considered him or a messiah/king from his descendants the son of God or divine.

But while Christians had a concrete messiah, Jews also hoped for one, and sometimes termed him the son of God.

4/11

But while Christians had a concrete messiah, Jews also hoped for one, and sometimes termed him the son of God.

4/11

So, perhaps Q 9:30 denounces both Jews and Christians for a similar claim, namely, that their respective messiah figures are “the son of God.”

But the name ʿUzayr is not a messianic title.

One solution is to opt for ʿ𝑎𝑧𝑖̄𝑧, which can mean prince/ruler.

5/11

But the name ʿUzayr is not a messianic title.

One solution is to opt for ʿ𝑎𝑧𝑖̄𝑧, which can mean prince/ruler.

5/11

Qur’an 12:78 uses ʿ𝑎𝑧𝑖̄𝑧 for Joseph as ruler of Egypt.

Similar titles are used for the Davidic king/messiah in the Bible & beyond (also hinted at: ).

Even the root ʿ-z-z is used in this context in Rabbinic literature (I owe this to a colleague)!

6/11

Similar titles are used for the Davidic king/messiah in the Bible & beyond (also hinted at: ).

Even the root ʿ-z-z is used in this context in Rabbinic literature (I owe this to a colleague)!

6/11

https://x.com/NaqadStudies/status/1767036279110131840?s=20

Also, the Qur’an associates David with strength (e.g., Q 38:17).

Yet ʿ𝑎𝑧𝑖̄𝑧 is not found in the readings or manuscripts (which is why I didn’t pursue the idea).

But 3 days ago a user pointed to 2 manuscript attestations!

Can ʿ𝑎𝑧𝑖̄𝑧 work?

7/11

Yet ʿ𝑎𝑧𝑖̄𝑧 is not found in the readings or manuscripts (which is why I didn’t pursue the idea).

But 3 days ago a user pointed to 2 manuscript attestations!

Can ʿ𝑎𝑧𝑖̄𝑧 work?

7/11

https://x.com/nyudim/status/1766433870054875329?s=20

Even the root ʿ-z-r itself can convey strength: ʿ𝑎𝑧𝑧𝑎𝑟𝑎 means “to strengthen/help” in Q 5:12, so it’s not impossible to read ʿ𝑢𝑧𝑎𝑦𝑟 in the sense of someone aided or strengthened by God (or promised strength/aid from God).

8/11

8/11

Maybe some Jews used ʿ𝑎𝑧𝑖̄𝑧 / ʿ𝑎𝑧𝑖̄𝑟 for the messiah—to avoid using 𝑚𝑎𝑠𝑖̄ℎ̣ b/c of its Christian associations?—and Qur’an chose its the diminutive form polemically?

But as a colleague pointed out, we would expect the definite 𝑎𝑙-ʿ𝑎𝑧𝑖̄𝑧, not ʿ𝑎𝑧𝑖̄𝑧.

9/11

But as a colleague pointed out, we would expect the definite 𝑎𝑙-ʿ𝑎𝑧𝑖̄𝑧, not ʿ𝑎𝑧𝑖̄𝑧.

9/11

Alternatively, one can perhaps still work with Ezra but consider Q 9:30 to reflect his hypothetical identification with Enoch and the latter’s identification as the Son of Man?

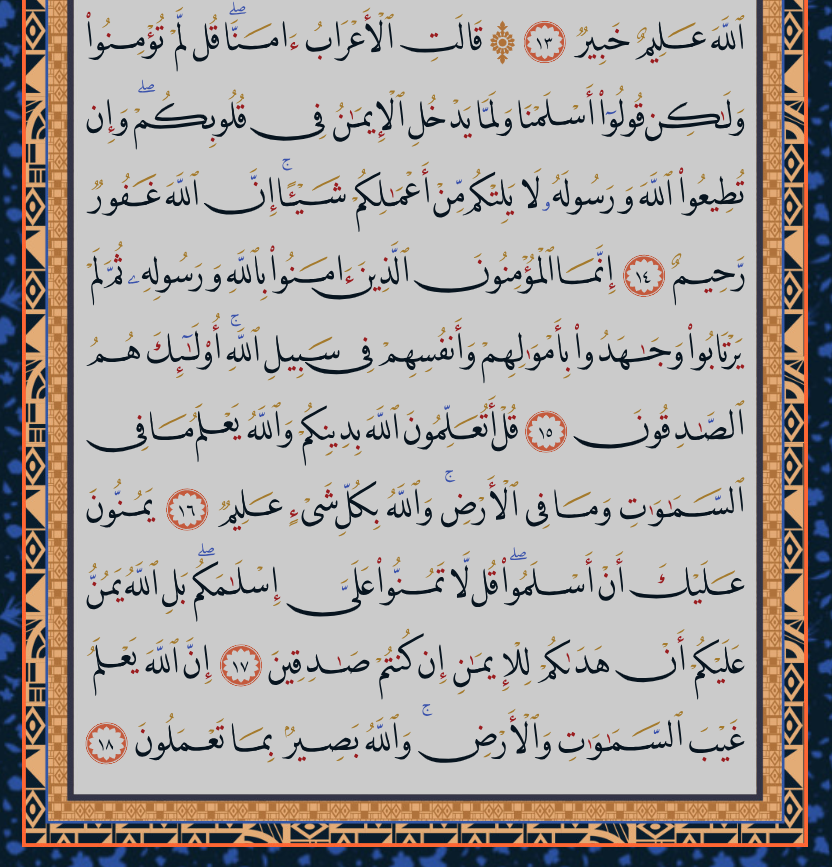

*Screenshots from Peter Schäfer’s Two Gods in Heaven

10/11

*Screenshots from Peter Schäfer’s Two Gods in Heaven

10/11

This is of course all very speculative.

But if the Qur’an consciously counter messianism (as argued skillfully by @GhaffarZishan), perhaps Q 9:30 is another part of that anti-messianic discourse--one that counters both Jewish and Christian messianism.

11/11

But if the Qur’an consciously counter messianism (as argued skillfully by @GhaffarZishan), perhaps Q 9:30 is another part of that anti-messianic discourse--one that counters both Jewish and Christian messianism.

11/11

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh