How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

https://x.com/MohsenGT/status/1866123935269425450

2/12 This statement, allegedly about religion’s perfection, appears between a long list of dietary prohibitions (“carrion, blood, pork, …”) & their concession clause (“whoever is forced by hunger …”).

2/12 This statement, allegedly about religion’s perfection, appears between a long list of dietary prohibitions (“carrion, blood, pork, …”) & their concession clause (“whoever is forced by hunger …”).

2/11 In the Qur’an, islām’s basic meaning is “giving all” (not “submission”), namely, giving all of one’s worship to Allāh—AKA monotheistic worship.

2/11 In the Qur’an, islām’s basic meaning is “giving all” (not “submission”), namely, giving all of one’s worship to Allāh—AKA monotheistic worship.

2/10 As I have argued, in the Qur’an dīn generally means “worship” (instead of “religion”) and islām denotes “monotheistic worship” (literally, “complete devotion [of one’s worship & self to Allāh]”).

2/10 As I have argued, in the Qur’an dīn generally means “worship” (instead of “religion”) and islām denotes “monotheistic worship” (literally, “complete devotion [of one’s worship & self to Allāh]”).https://twitter.com/MohsenGT/status/1763641421800599775

2/15 For example, Q 3:79-80 asserts that a prophet (like Jesus) would never ask people to serve him or other beings instead of God. “Would he command you to disbelieve after you have been 𝘮𝘶𝘴𝘭𝘪𝘮?” The point is that Israelites were monotheists (𝘮𝘶𝘴𝘭𝘪𝘮) before Jesus ...

2/15 For example, Q 3:79-80 asserts that a prophet (like Jesus) would never ask people to serve him or other beings instead of God. “Would he command you to disbelieve after you have been 𝘮𝘶𝘴𝘭𝘪𝘮?” The point is that Israelites were monotheists (𝘮𝘶𝘴𝘭𝘪𝘮) before Jesus ...

2/14 I have argued that dīn in the Qur’an means “service” or “worship,” not “religion”

2/14 I have argued that dīn in the Qur’an means “service” or “worship,” not “religion”https://x.com/MohsenGT/status/1742232515673256096

https://x.com/MohsenGT/status/1655572610954981377?s=20

2/11 For example, Q 3:83 wonders if some Christians seek something other than “dīn Allāh.”

2/11 For example, Q 3:83 wonders if some Christians seek something other than “dīn Allāh.”

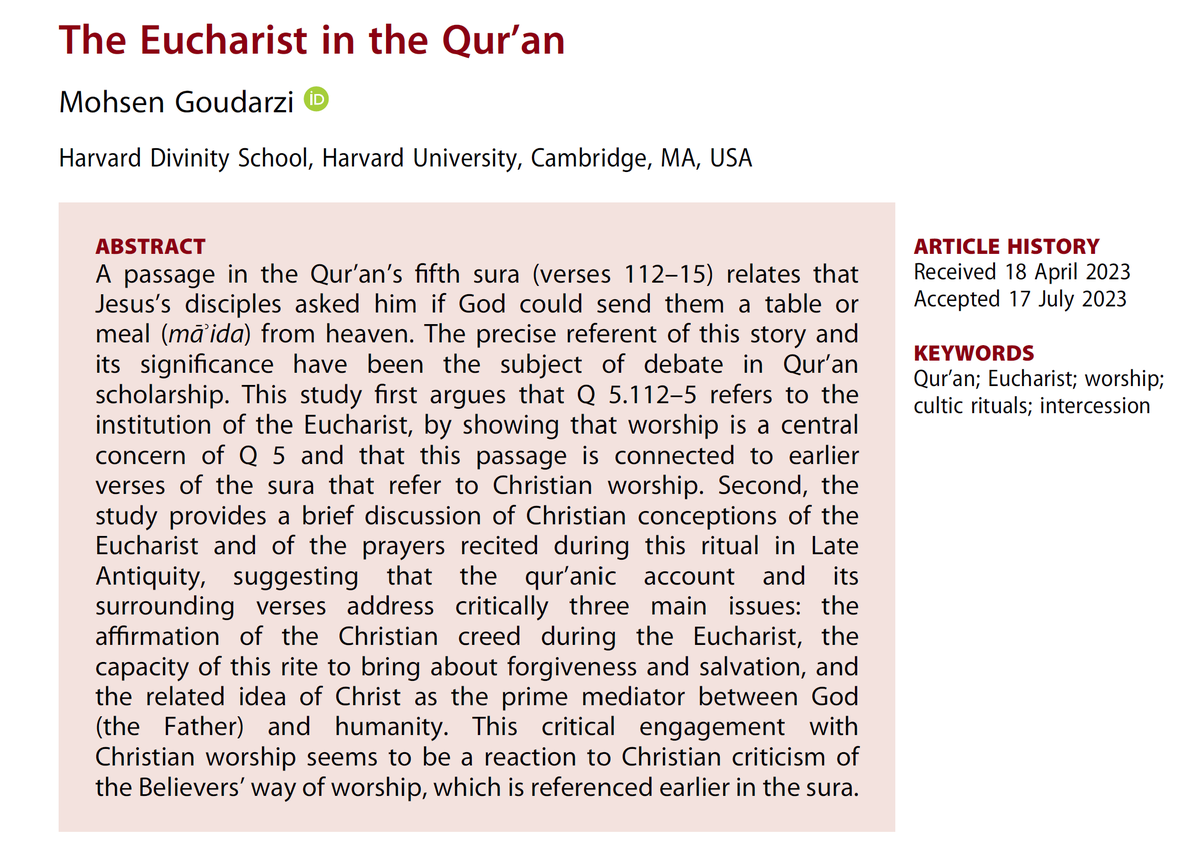

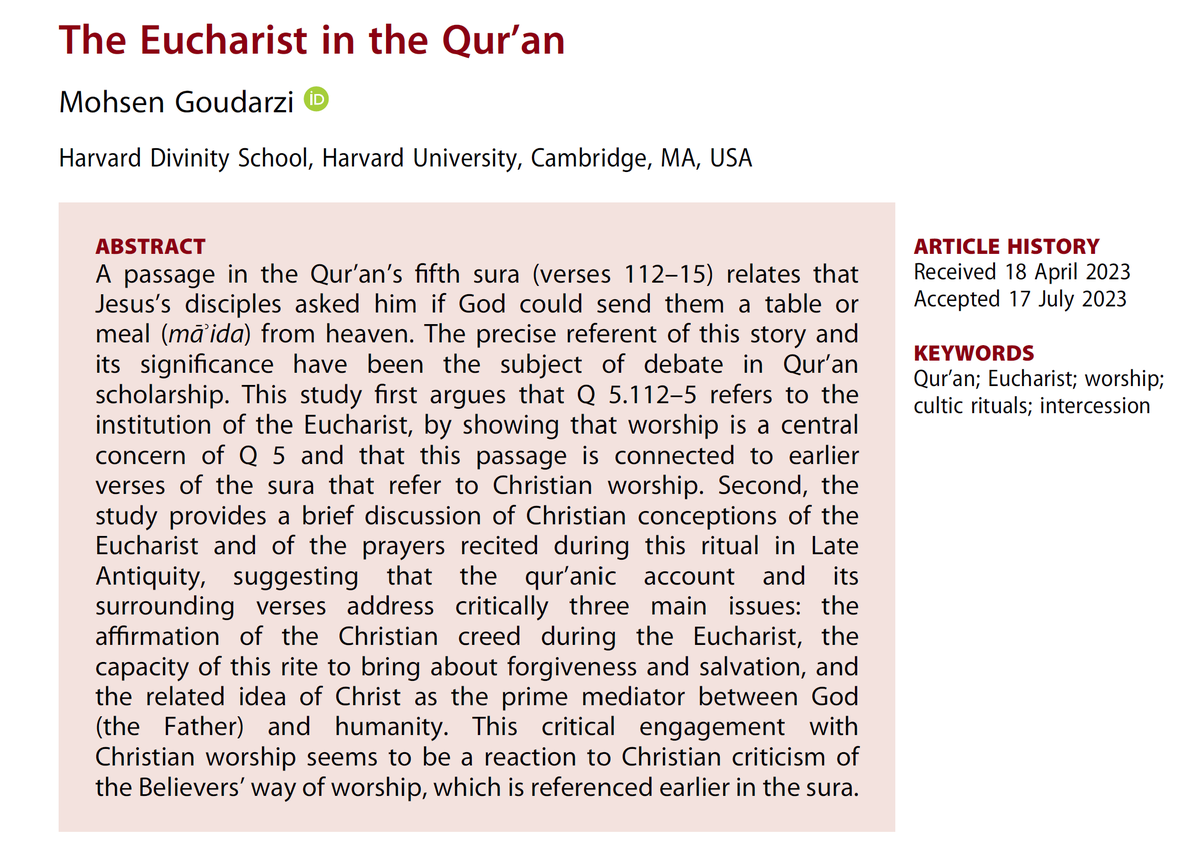

Worship & its rituals are a major theme of Qur'an's 5th surah. Its beginning prohibits hunting during worship by the Sanctuary (vv. 1-4) & requires purification before cultic prayer (ṣalāt, v. 6). Similar subjects are further treated later in the surah as well (vv. 87-103).

Worship & its rituals are a major theme of Qur'an's 5th surah. Its beginning prohibits hunting during worship by the Sanctuary (vv. 1-4) & requires purification before cultic prayer (ṣalāt, v. 6). Similar subjects are further treated later in the surah as well (vv. 87-103).

https://twitter.com/MohsenGT/status/1655572610954981377?s=20

2/12 Dīn is often translated as “religion” or “faith.” But IMO dīn mostly means “(way of) worship,” reflects the meaning of “service” or “servitude” that is conveyed by dīn or dāna outside Quran, and often evokes cultic rituals (e.g., ṣalāt, sacrifices, Eucharist).

2/12 Dīn is often translated as “religion” or “faith.” But IMO dīn mostly means “(way of) worship,” reflects the meaning of “service” or “servitude” that is conveyed by dīn or dāna outside Quran, and often evokes cultic rituals (e.g., ṣalāt, sacrifices, Eucharist).

Let us look at al-Baqarah, which contains an extensive discussion of the emergence of Believers as a new community.

Let us look at al-Baqarah, which contains an extensive discussion of the emergence of Believers as a new community.

TL;DR: Ottoman scholars were not avid fans of tradition-based exegesis (al-tafsīr bi-l-maʾthūr). They were mostly interested in analytical tafsīr, in particular those of al-Rāzī, al-Zamakhsharī, & al-Bayḍāwī. They were also busy reading & writing glosses (esp. on latter 2).

TL;DR: Ottoman scholars were not avid fans of tradition-based exegesis (al-tafsīr bi-l-maʾthūr). They were mostly interested in analytical tafsīr, in particular those of al-Rāzī, al-Zamakhsharī, & al-Bayḍāwī. They were also busy reading & writing glosses (esp. on latter 2).