Why have British sea-fronts gone from Tourism hotspots to Housing Benefit hotspots?

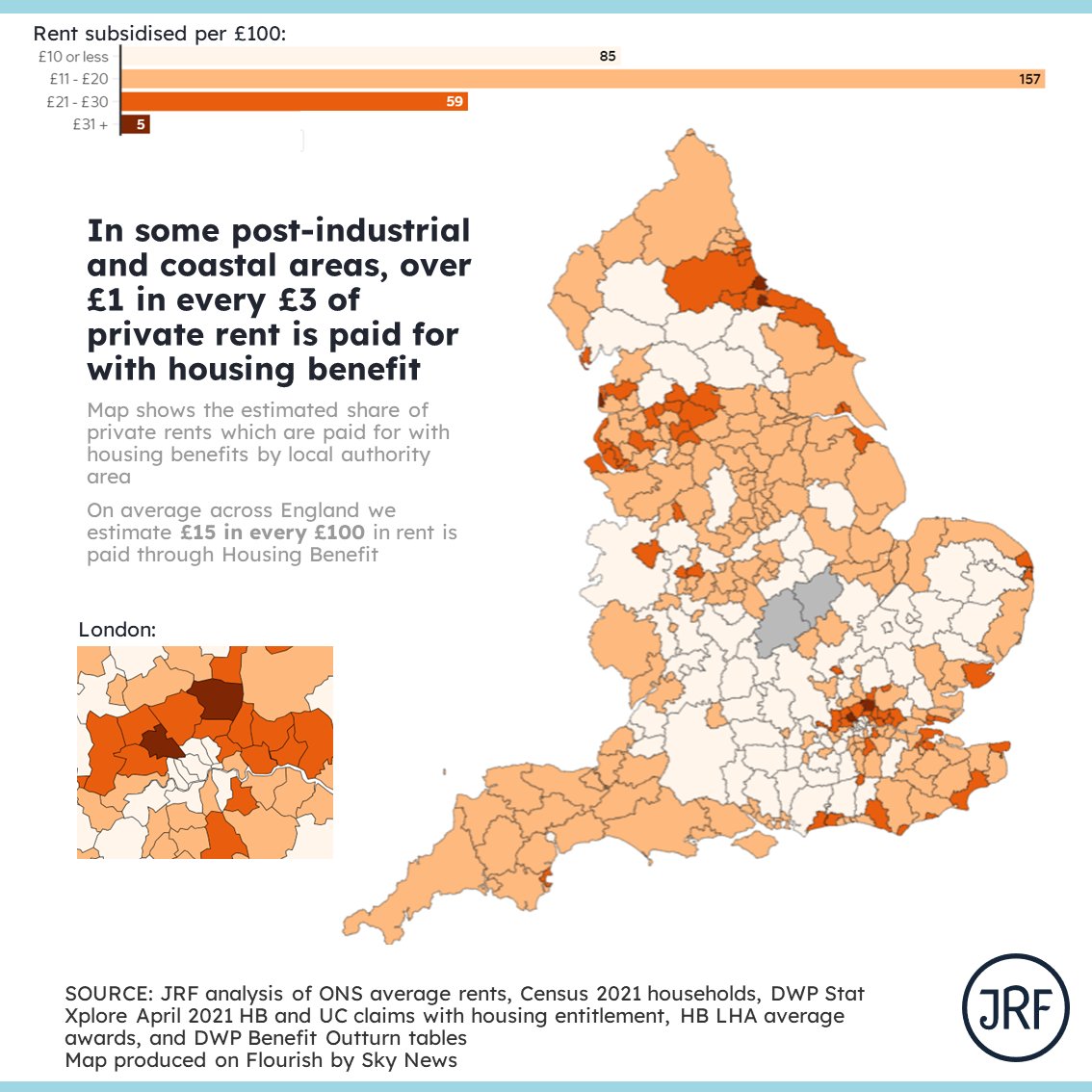

Take Blackpool - along the seafront there are over 6 private rented HB claims for every 10 households (of all tenures), with over £1 in every £3 in rent paid through housing benefit.

🧵⬇️

Take Blackpool - along the seafront there are over 6 private rented HB claims for every 10 households (of all tenures), with over £1 in every £3 in rent paid through housing benefit.

🧵⬇️

This isn't constrained to seafronts, we also see disproportionately high private rental housing benefit claims in:

- The centres of post-industrial cities and towns

- The centres of post-industrial cities and towns

- And in the outer areas of 'core' cities, such as Manchester, Birmingham, London, Liverpool and Leeds.

Across England we're handing £9bn a year in housing benefit to private landlords.

In some areas, including some seaside and post-industrial cities and towns, but also Enfield and Brent, over £1 in every £3 of rent paid is paid through HB.

So what's going on??

In some areas, including some seaside and post-industrial cities and towns, but also Enfield and Brent, over £1 in every £3 of rent paid is paid through HB.

So what's going on??

Across these areas and core (and other) cities generally we've seen a large growth in the share of homes and households that are private rented/ers.

Though house and rental prices between post-industrial areas and core cities tend to be on opposite ends of the spectrum..

Though house and rental prices between post-industrial areas and core cities tend to be on opposite ends of the spectrum..

In costal towns and post-industrial areas high rates of HB claims are driven by strong push-pull factors:

- Weakening tourist industry in coastal areas means surplus housing, bought by landlords and rented out, with comparatively cheaper rents pulling in those on low-incomes..

- Weakening tourist industry in coastal areas means surplus housing, bought by landlords and rented out, with comparatively cheaper rents pulling in those on low-incomes..

- In post-industrial areas, the often smaller, poorer quality and less desirable homes in town centres are acquired by private landlords and let at lower rent levels pulling in those on low-incomes who often require housing benefit to help cover rent.

- But at the same time people on low-incomes are pushed away from more desirable and less affordable areas - including cities, where there is a higher demand for homes, and the shortage of homes (and - for these groups - shortage of social housing) is sharpest.

- But these coastal cities and post-industrial towns have much weaker labour markets, fewer jobs and much lower average wages - meaning many are unemployed or are 'economically inactive'

In core cities, the trend is reversed; with large numbers of typically younger adults renting typically smaller homes in more central parts of cities, often sharing - closer to jobs, amenities, etc.

And a 'ring' of housing benefits claims for private renters encircles the cities, with lower-income households pushed to the less unaffordable outer areas of these large cities - a phenomenon described by some academics as the 'suburbanisation' of poverty.

High rents in often more desirable city centres price out the lower income families, and push them to outer areas of these larger cities, a trend seen in Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, Bristol, among others.

The trend is much less prevalent among other cities (University, Historic or Commuter) cities including York, Canterbury and Cambridge.

It's likely the sheer scarcity of homes means many low-income families who would like to live in these areas are simply priced out.

It's likely the sheer scarcity of homes means many low-income families who would like to live in these areas are simply priced out.

What's the upshot?

A very extractivist model of private landlordism has become increasingly prevalent across Britain in the last few decades.

The sector has expanded rapidly, and particularly in coastal and post-industrial towns / cities and other cities.

A very extractivist model of private landlordism has become increasingly prevalent across Britain in the last few decades.

The sector has expanded rapidly, and particularly in coastal and post-industrial towns / cities and other cities.

Too often it sucks up too much of low-income families earnings and public subsidy through housing benefit.

In return, low-income renters are stuck in often inadequate, poor quality homes - sometimes in dangerous condition.

In return, low-income renters are stuck in often inadequate, poor quality homes - sometimes in dangerous condition.

In a report we've published today - we argue for intervention to take this on.

Step one needs to be higher standard and enforcement of standards in the Private Rented Sector

With greater protections for tenants - through the Renters Reform Bill

Step one needs to be higher standard and enforcement of standards in the Private Rented Sector

With greater protections for tenants - through the Renters Reform Bill

- We also desperately need to see an shift in gear in the development of homes - with more homes, particularly social homes, built. We particularly need to see these in places where there are job opportunities.

In our report we also argue for some homes to be brought into social ownership to make temporary accommodation cheaper, to drive up housing standards in lower-cost areas, including by growing the community rental sector.

We also want to see reform of Right to Buy - so that discounts are baked in and kept in the system, discounts are capped at 30%, and allowing councils to keep 100% of receipts.

Read more in our new @JRF_UK report from @DarrenBaxter with analysis from me:

jrf.org.uk/housing/bringi…

jrf.org.uk/housing/bringi…

Coverage from @FionaMackieSky @joelysantacruz @DanielJDunford and @NickMartinSKY from @SkyNews for covering the report here:

news.sky.com/story/the-seas…

news.sky.com/story/the-seas…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh