Interesting paper and an insightful comment by @akoustov. Let me take this opportunity to summarise some of the (climate-focused) literature on elite cues. 1/n

https://twitter.com/akoustov/status/1769761877611909365

First: Why do elite cues matter? Because, if they work, it means elites can sometimes impose their own agenda on the public – rather than being guided by public opinion in devoting their attention to certain issues.

Barberá et al. demonstrate the empirical importance ... 2/n

Barberá et al. demonstrate the empirical importance ... 2/n

of elite cues using social media data.

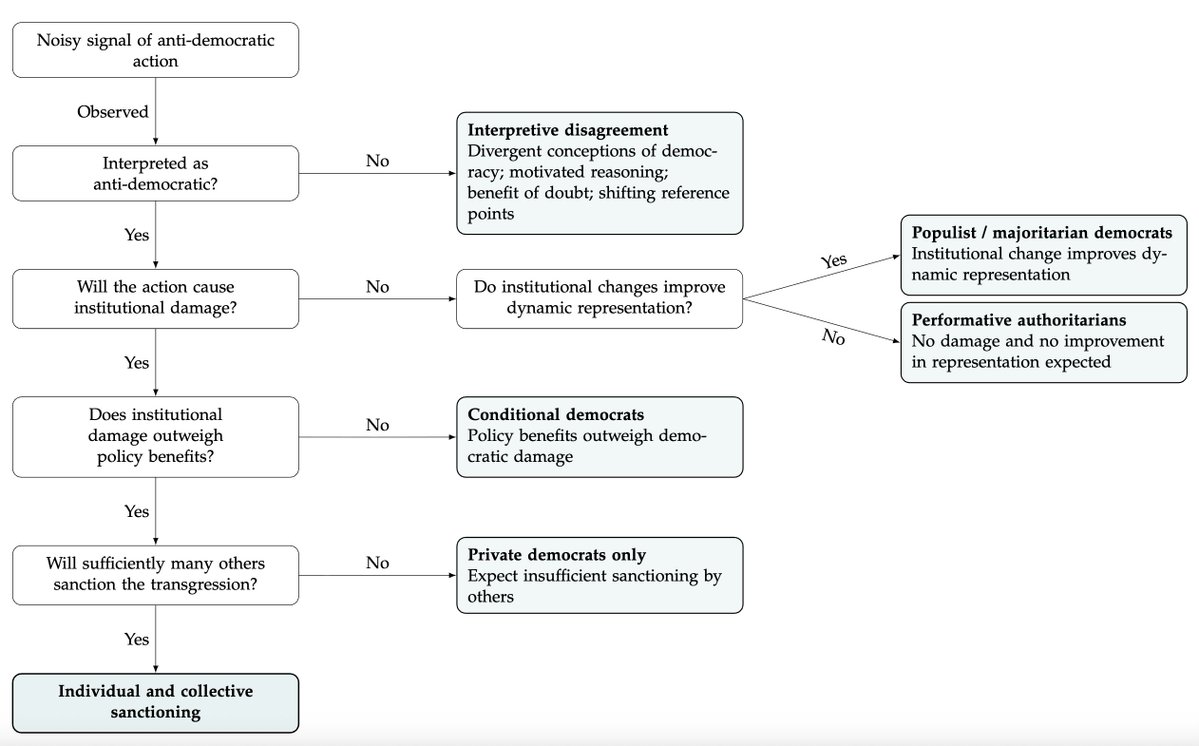

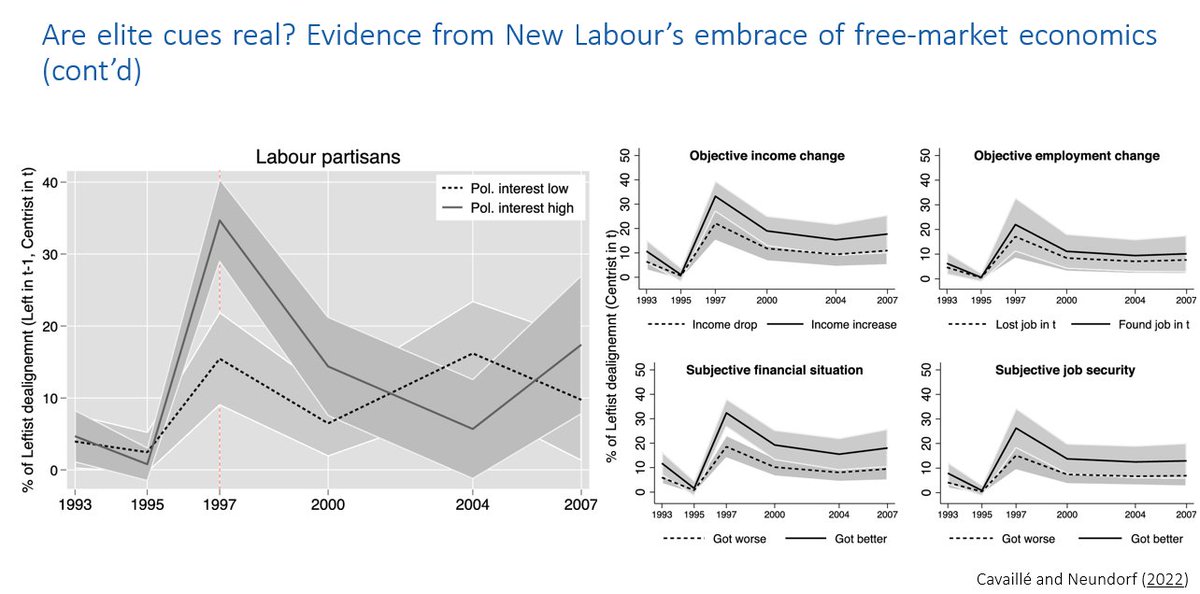

Second: Who responds to elite cues? Here I'd like to summarise two recent studies. The first is by @CharlotteCavai1 and @AnjaNeundorf. They draw on and amend Zaller's theory of public opinion to develop ...

3/n cambridge.org/core/journals/…

Second: Who responds to elite cues? Here I'd like to summarise two recent studies. The first is by @CharlotteCavai1 and @AnjaNeundorf. They draw on and amend Zaller's theory of public opinion to develop ...

3/n cambridge.org/core/journals/…

and test an intriguing argument as to who is most responsive to elite cues - in the context of New Labour's embrace of free-market economics (see 👇).

Zaller argues that those who pay the most attention to politics / are most interested in politics are most susceptible ...

4/n

Zaller argues that those who pay the most attention to politics / are most interested in politics are most susceptible ...

4/n

to elite cues. The authors add the twist that this effect is moderated by material self-interest: when elite cues go against the latter, one is all else equal less susceptible to them.

Using panel data, they provide evidence in favour of these hypotheses. Those who ... 5/n

Using panel data, they provide evidence in favour of these hypotheses. Those who ... 5/n

struggled financially, were less likely to follow the party grandees by adopting less redistributive attitudes / more pro-market attitudes.

Slothuus and Bisgaard's @AJPS_Editor paper shows that elite cues are not just a British thing, as it were.

6/nonlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.111…

Slothuus and Bisgaard's @AJPS_Editor paper shows that elite cues are not just a British thing, as it were.

6/nonlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.111…

They leverage the sudden change in the position of the Liberals / DPP in Denmark on unemployment benefits to tease out the effect of elite cues. They show that their supporters become significantly more likely to support these policies after parties change their position. 7/n

@mbarber83 and Pope's nice @PSRMJournal piece makes another important point: elite cues are weakest for issues about which respondents care a great deal. Put differently, elites have the most influence on issues where citizens have either weak ...

8/n cambridge.org/core/journals/…

8/n cambridge.org/core/journals/…

or unstructured preferences.

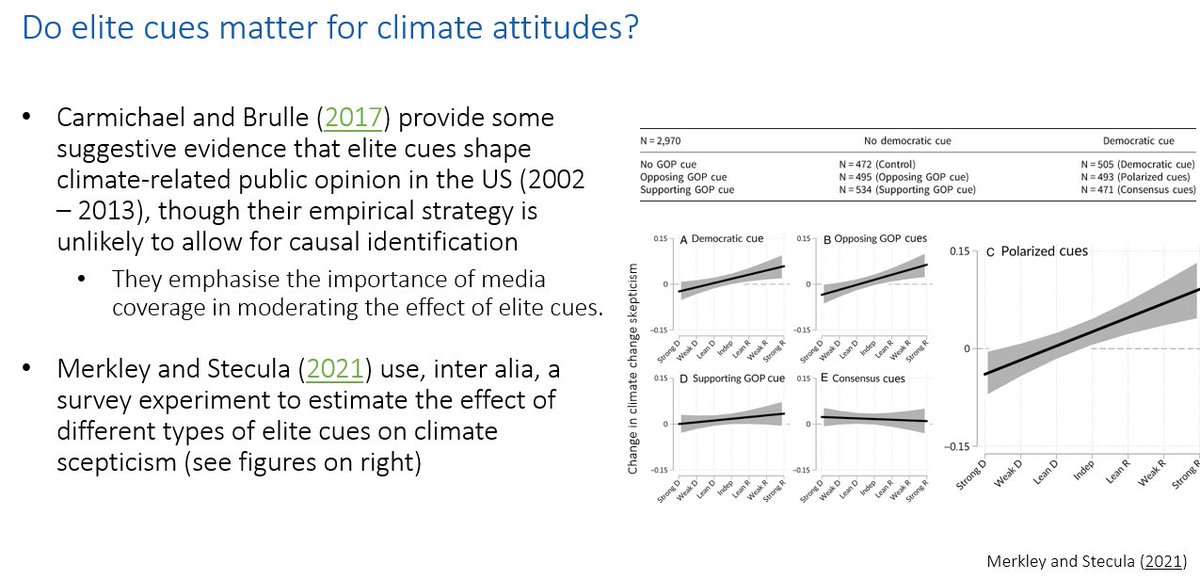

Finally: Do elite cues matter for climate policy? Merkley and @decustecu show that elite cues can affect climate scepticism. But the paper linked to above by @akoustov shows that changing beliefs about climate change ...

9/n cambridge.org/core/journals/…

Finally: Do elite cues matter for climate policy? Merkley and @decustecu show that elite cues can affect climate scepticism. But the paper linked to above by @akoustov shows that changing beliefs about climate change ...

9/n cambridge.org/core/journals/…

is quite different from changing policy preferences.

So where does that leave us? See👇for my summary. /END

So where does that leave us? See👇for my summary. /END

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh