views

I'm being frequently asked to offer clarity on what is legal and illegal under international humanitarian law. In this thread I will try to offer some clarity in the hopes that folks find it useful.🧵

In armed conflict against non-state actors, to lawfully target a person, states need to verify that the target is "directly participating in hostilities". Militaries and humanitarian actors disagree on what this means in practice, but there are some basic minimum standards

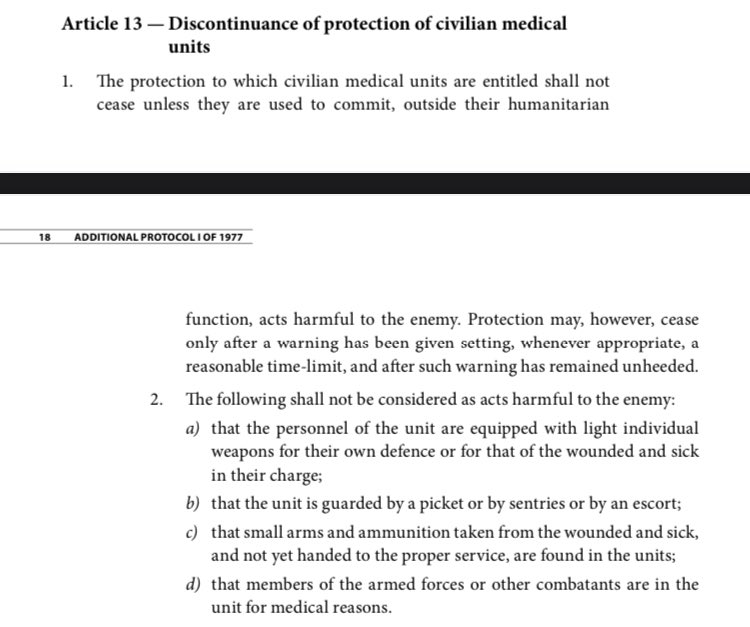

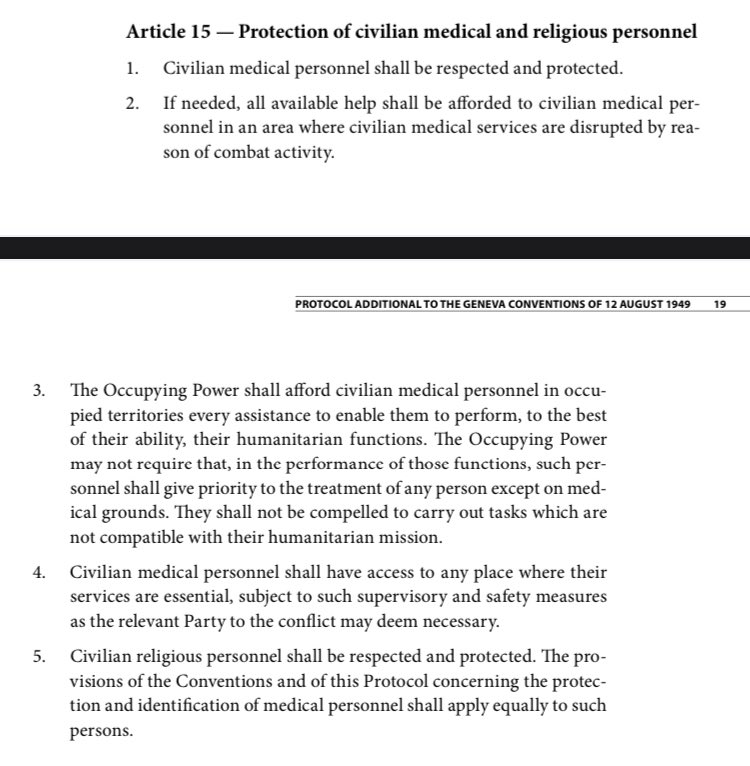

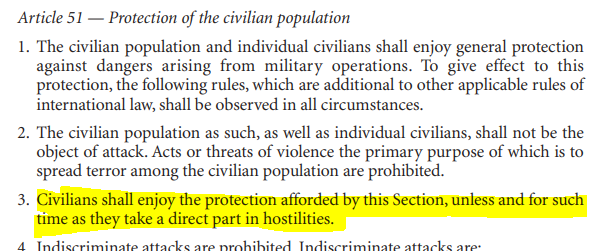

The basic rule, of course, is that civilians are not targets. Art. 51(3) of Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions, which is also undisputably a customary rule applicable to all armed conflicts, is clear. They therefore need to be "distinguished" from combatants

The text of Art. 51(3) raises two key questions: 1) when is participation direct? and 2) how should "unless and for such time" be interpreted? Let's answer them one by one

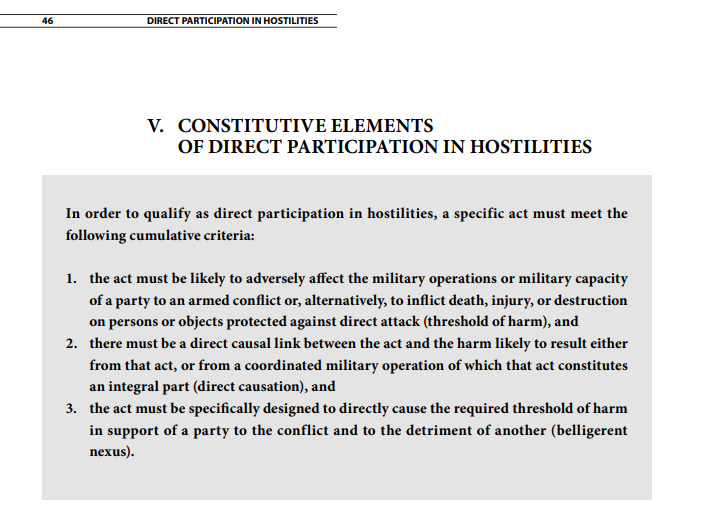

According to the @ICRC, "direct" participation requires 1) a minimum threshold of harm, 2) a direct causal link between that harm and the act in question, and 3) a belligerent nexus. Let's look into them one by one (and for more info, see here: ) icrc.org/en/doc/assets/…

Threshold of Harm: The act has to harm an armed force's military objectives or, if it does not, it has to directly cause death, injury or destruction on civilians or civilian objects.

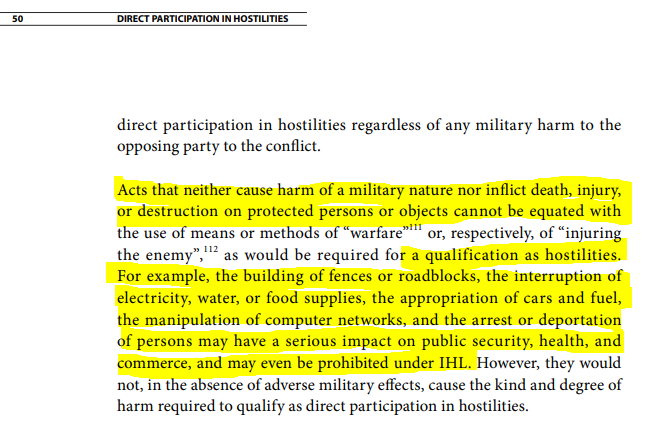

For example, if a Palestinian civilian gives food to a Hamas fighter is helping them, but not to the degree that would warrant a military response and so cannot be targeted for it (see here: ) nyujilp.org/wp-content/upl…

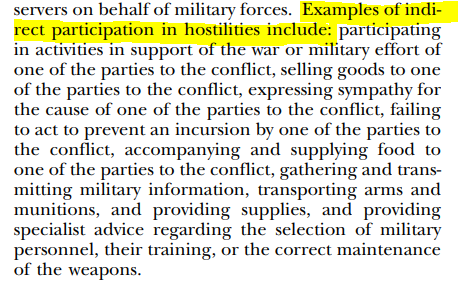

Direct Causation: If the harm reaches a sufficient level of harm, this must still be "direct", as opposed to "indirect". Take, for example, a financist moving money around to help an armed group avoid sanctions. Their actions harm the state armed forces, but not "directly"

Here there is an interesting case to analyse: usually, civilian researchers are also considered "indirect" participation. But what about Oppenheimer or Turing during WWII? Was their research "indirect"? Or "direct"? Experts disagree. Per the ICRC:

Belligerent nexus: Even if the act is harmful enough and directly affects the armed forces, they still need to be connected to the conflict in question. This is an objective fact, and not a matter of intent.

The clearest example here is that of a criminal gang robbing a bank during an armed conflict to steal their wallet. The harm crosses the threshold and directly harms infrastructure, but is not connected to the hostilities. The gang cannot be blown to bits by the army in response

How you read these rules matters. You can read them broadly or narrowly. This will determine how easily you conclude that someone can be killed. And it is easy to use legal rules to circumvent moral reservations. This is why my position is these rules must be interpreted narrowly

To take an extreme example: are the Israeli civilians blocking aid into Gaza directly participating in hostilities and can they be targeted by Hamas under the argument that their harm causes direct and conflict-related injury to its militants? I think not.

But those who take a more hawkish view of these standards, because, say, they want to be able to kill a *cleric* who is *saying* things that are influencing *other people* to commit attacks (as the US did in 2011), might not have such an easy time reaching that same conclusion

And that is the thing: in the law of armed conflict, what is valid for one party to the conflict is also valid for the other party to the conflict. So, in general, always interpret the rules in the way you want them to be interpreted for yourself.

Now that we know when participation is "direct", we need to determine when it starts and ends - the "unless and for such time" component. Here, there is also disagreement.

The original drafting suggests that direct participation is always temporary. "Unless and for such time" suggests that civilians lose and regain protection depending on whether they are, at any given time, directly participating or not. As per the ICRC:

In other words, if a civilian picks up a weapon, shoots at a soldier and runs, if the army then finds them in their home later that day, it cannot just kill him. The civilian, while at home, is no longer participating in hostilities and cannot be attacked. Merely detained.

This has always been resented by militaries, who say it is absurd to conclude, for instance, that bin Laden was only targetable whenever he was directly engaged in an attack. There's been much debate with regards to how long can loss of protection last.

It is generally accepted therefore that when a civilian joins an armed force they cease to be civilians. A "member of Hamas", for instance, is not a civilian. The thing is, when does someone become a member of Hamas?

For the US, for instance, simply swearing an oath to al-Qaeda was enough to turn someone into a "member" and lose all civilian protections. Similarly, are non-combat "members", members? Is a Hamas cook or driver "not a civilian" anymore? see here: papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

For the ICRC, the key is whether the individual has a "continuous combat function" in the group. These members can be targeted at any time, without need for them to pick up a weapon and shoot.

But does this mean that if the army finds a "member" having a drink in a cafe, they can shoot him point blank execution style no questions asked? Experts again disagree. According to Marco Sassoli:

There is of course a lot more to discuss, and I may add more tweets to this thread, but for now, this is a good enough crash course. Hopefully this will help you understand targeting issues better.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh