1. Laocoön and His Sons (c.323 BC - 31 AD)

The first truly advanced and naturalistic sculptures came from Ancient Greece - marble was the preferred medium from which to extract extreme detail. And they usually depicted idealized human anatomies...

The first truly advanced and naturalistic sculptures came from Ancient Greece - marble was the preferred medium from which to extract extreme detail. And they usually depicted idealized human anatomies...

This one came from the Hellenistic era, when sculptures accelerated from static, graceful figures to far more expressive ones.

Because this was rediscovered in Rome during the Renaissance, many thought it wasn't genuine, and that Michelangelo himself must've carved it.

Because this was rediscovered in Rome during the Renaissance, many thought it wasn't genuine, and that Michelangelo himself must've carved it.

2. Augustus of Prima Porta (c.20 BC)

The Romans inherited the love of marble, often reproducing old Greek bronzes with stone. The Ancient Greeks had depicted their gods as naturalistic, earthly figures - the Romans instead carved their human rulers as glorious and godlike.

The Romans inherited the love of marble, often reproducing old Greek bronzes with stone. The Ancient Greeks had depicted their gods as naturalistic, earthly figures - the Romans instead carved their human rulers as glorious and godlike.

3. Pisa Baptistery pulpit - Giovanni Pisano (1310)

Medieval sculpture focused less on realistic, life-sized subjects, and more on symbolic, religious scenes. Stylized reliefs and statues of Biblical events were made for altarpieces, pulpits and church façades across Europe...

Medieval sculpture focused less on realistic, life-sized subjects, and more on symbolic, religious scenes. Stylized reliefs and statues of Biblical events were made for altarpieces, pulpits and church façades across Europe...

4. La Pietà - Michelangelo (1499)

The Italian Renaissance was the first time the mastery of the Greeks was surpassed, and interest in naturalism renewed. A 24-year-old Michelangelo stunned Rome when he unveiled this depiction of Mary and Jesus...

The Italian Renaissance was the first time the mastery of the Greeks was surpassed, and interest in naturalism renewed. A 24-year-old Michelangelo stunned Rome when he unveiled this depiction of Mary and Jesus...

Classical beauty and naturalism were now combined in a new way:

The human forms are idealized and Mary appears youthful and serene. But she also has an expression of deepest grief, and the anatomical precision took things to an entirely new level.

The human forms are idealized and Mary appears youthful and serene. But she also has an expression of deepest grief, and the anatomical precision took things to an entirely new level.

5. David - Michelangelo (1504)

Still in his twenties, Michelangelo defined Renaissance art yet again. David was a classical expression of what man can be...

Still in his twenties, Michelangelo defined Renaissance art yet again. David was a classical expression of what man can be...

But he went far further than the Greeks could - incorporating anatomical accuracies he learned from dissecting corpses.

A century later, scientists made anatomical discoveries that Michelangelo knew - like the bulging jugular vein fitting for someone in a state of fear...

A century later, scientists made anatomical discoveries that Michelangelo knew - like the bulging jugular vein fitting for someone in a state of fear...

Michelangelo was the ultimate naturalist: he believed his goal was "to liberate the human form trapped inside the block by gradually chipping away at the stone surface".

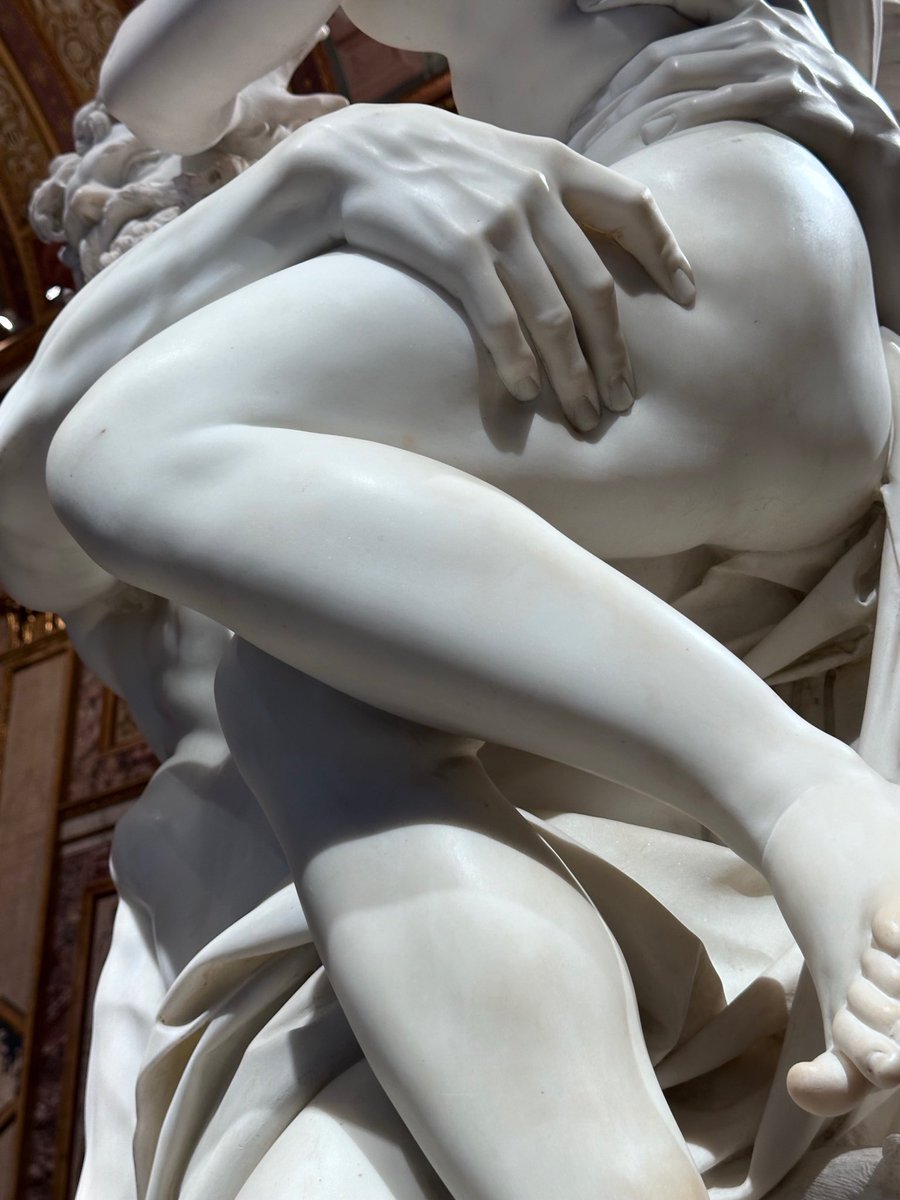

6. The Abduction of Proserpina, Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1622)

The Baroque era saw new energy and movement injected into marble. Motion is evident if every inch of Bernini's depiction of Pluto dragging Proserpina off to the underworld...

The Baroque era saw new energy and movement injected into marble. Motion is evident if every inch of Bernini's depiction of Pluto dragging Proserpina off to the underworld...

To exemplify the shift in focus, just look at the difference between Michelangelo's David and Bernini's version.

7. Release from Deception - Francesco Queirolo (1759)

The medium was stretched to its technical extreme in the Rococo era. One Italian master spent 7 years of his life carving this unthinkably intricate net from a single block of stone...

The medium was stretched to its technical extreme in the Rococo era. One Italian master spent 7 years of his life carving this unthinkably intricate net from a single block of stone...

Artists in his era continually one-upped each other with more and more difficult technical feats. A few years earlier, contemporaries of Queirolo unveiled these: Sanmartino's "Veiled Christ" and Corradini's "Modesty".

8. The Three Graces - Antonio Canova (1817)

The neoclassical era took sculpture back to the graceful, classical ideal. Many consider Canova the last great sculptor of marble - he could carve almost anything from it, his biggest leap being impossibly supple skin.

The neoclassical era took sculpture back to the graceful, classical ideal. Many consider Canova the last great sculptor of marble - he could carve almost anything from it, his biggest leap being impossibly supple skin.

9. The Veiled Virgin - Giovanni Strazza (c.1850)

The exquisite draperies from antiquity were finally perfected in the 19th century: solid stone could be made translucent. Probably nobody took this further than Strazza did with his depiction of the Virgin Mary...

The exquisite draperies from antiquity were finally perfected in the 19th century: solid stone could be made translucent. Probably nobody took this further than Strazza did with his depiction of the Virgin Mary...

At the turn of the 20th century, modern sculptors like Rodin executed their best works in other mediums (like bronze), but with no lesser craftsmanship. His epic bronze Gates of Hell took 37 years to finish.

After Rodin, marble was still used fairly regularly, but in an abstract sense. The properties of marble, like its luminosity, were from then on used for reasons other than realism.

So why did we stop producing marble sculpture of earlier standards?

Perhaps it was the stifling cost of the stone, or maybe all that could be achieved with marble had already been done...

Perhaps it was the stifling cost of the stone, or maybe all that could be achieved with marble had already been done...

Or perhaps we simply lost the necessary conviction - marble is so unforgiving that a single mistake can undo years of work.

A better question might be: what inspired them to do it in the first place?

A better question might be: what inspired them to do it in the first place?

If threads like this interest you, you NEED my weekly newsletter (free)!

Art, culture and history - 25,000 other readers 👇

culturecritic.beehiiv.com/subscribe

Art, culture and history - 25,000 other readers 👇

culturecritic.beehiiv.com/subscribe

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh