Pompeii and Herculaneum have provided some of the most beautiful and well-preserved frescoes of the Greco-Roman tradition. Yet there exists a remarkable find that predates them by 300 years.

Let me tell you about my visit to the Macedonian Tomb of Agios Athanasios:🧵

Let me tell you about my visit to the Macedonian Tomb of Agios Athanasios:🧵

Located ~20 kilometers west of Thessaloniki, the village of Agios Athanasios is your typical sleepy rural town. What is unique are two large mounds, one of them covered in pine trees and foliage. In 1994, a farmer discovered that they contained ancient tombs.

After an official excavation, it was determined that they both dated to the late fourth/early third century BC, typical burial types of the Macedonian nobility, most famously like that of Philip II at Aigai (Vergina)

As they descended into larger tomb, already looted millennia earlier, they found a magnificent treasure: a series of splendid frescoes adorning its façade in an almost perfect state of preservation.

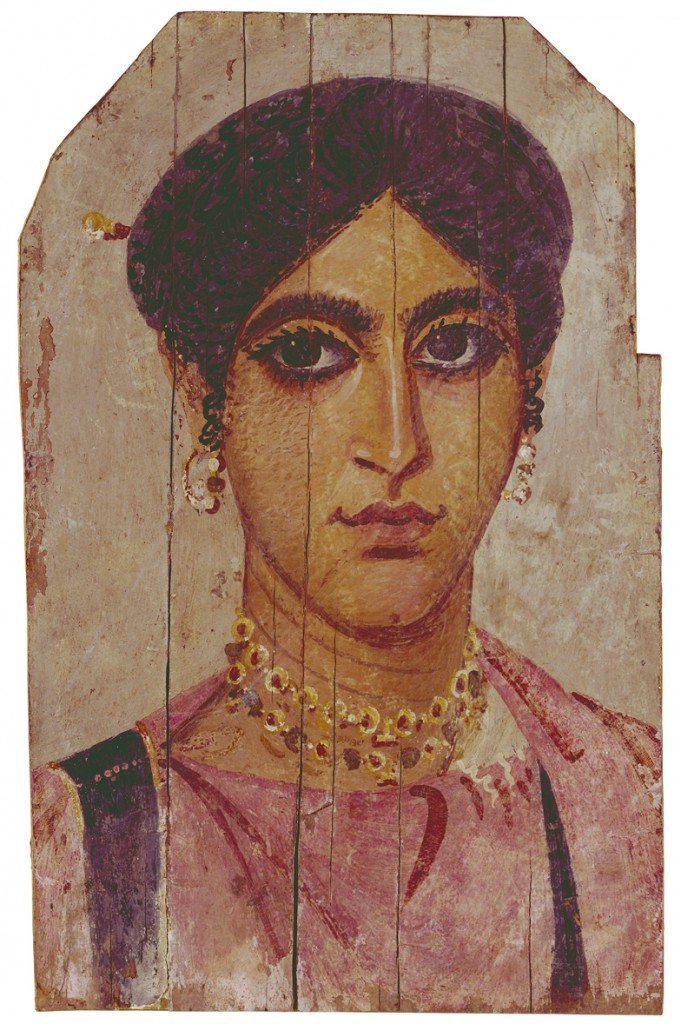

Scholars knew that such paintings existed during the Classical and Hellenistic periods, but surviving examples were extremely rare and in rough shape: for instance, this find from the Vergina Tombs. The Agios Athanasios finds are shockingly good in comparison.

On each side of the doorway are two large guards wearing the traditional outfit of the Macedonians: a military cloak ("chlamys") and the distinctive broad-brimmed "kausia", along with the long spear (sarissa). Notice they appear in a state of mourning and eternal vigilance.

The top right corner shows a procession of warriors. These are very likely members of the Macedonian nobility that were a part of the king's inner circle and court, either his Companions ("hetairoi") or even his bodyguards ("somatophylakes").

The top left frieze seems to show the same group of men on horseback (thus confirming their social rank), though in a more celebratory procession

Most curious is the middle frieze, which depicts a symposium: the nobles are gathered in a drinking party, and this is one of the few pieces of evidence showing domestic life like tables and couches, which otherwise have long decomposed

Who is the occupant of this tomb? Clearly they were a man of some means. If we look at each of the reliefs, one face is consistent, and is looking directly at the observer. This fellow must be the occupant, and likely served alongside Alexander the Great and/or the Diadochi

I had the pleasure of visiting this tomb during my most recent trip to Greece, and if you are ever in Thessaloniki for an extended stay, I strongly encourage you to make a detour to here and see such an incredible collection of paintings up close and in their original context.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh