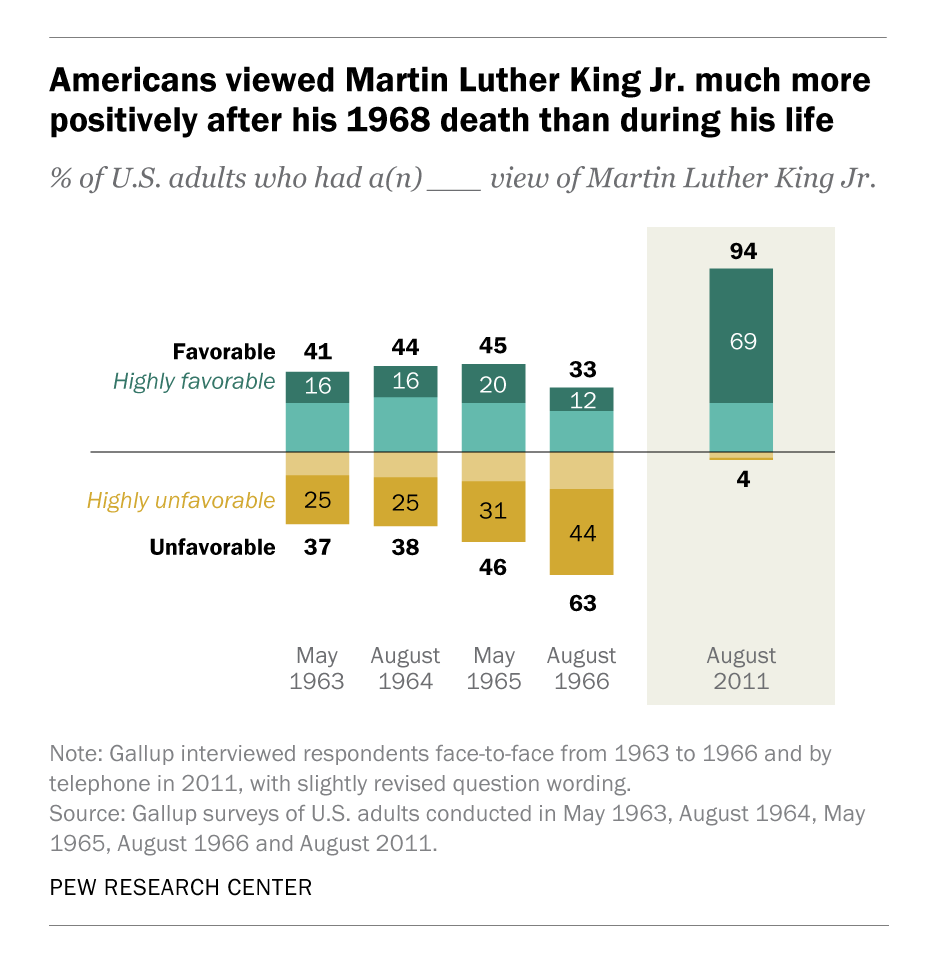

The American nuclear industry illustrates negative learning: the costs of plants have increased over time.

But this is not nuclear's fault. Almost everywhere else, the learning rate is positive: costs decline as the industry gains experience building!

🧵

Consider France:

But this is not nuclear's fault. Almost everywhere else, the learning rate is positive: costs decline as the industry gains experience building!

🧵

Consider France:

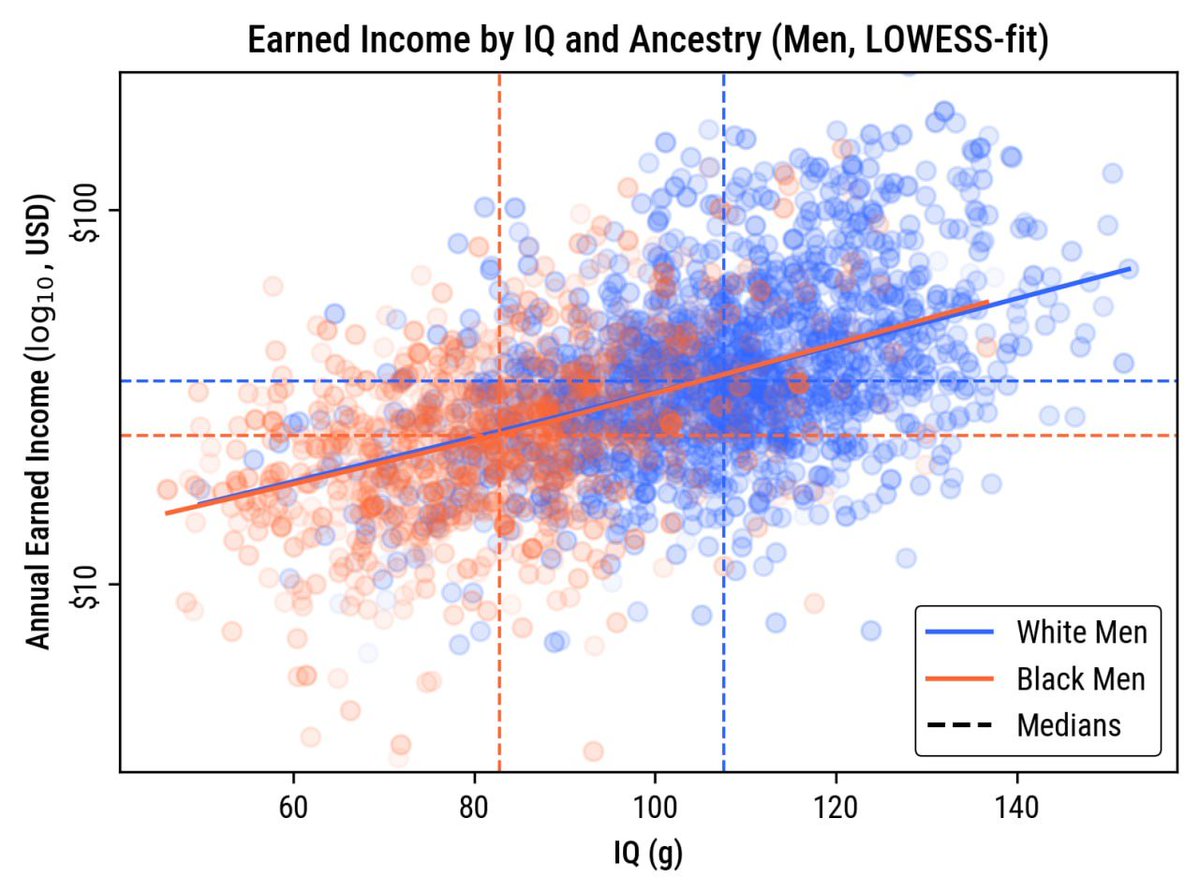

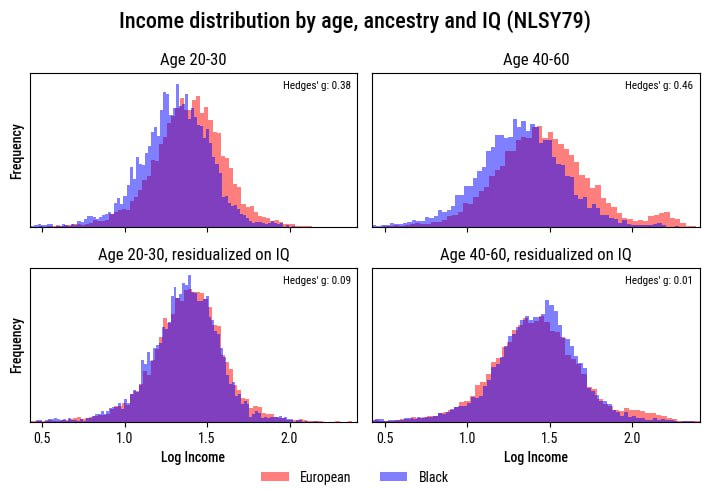

The U.S. has really only been experiencing cost overruns since the Three Mile Island incident, and the reason has to do with the industry becoming overregulated as a result of the public outcry that ensued.

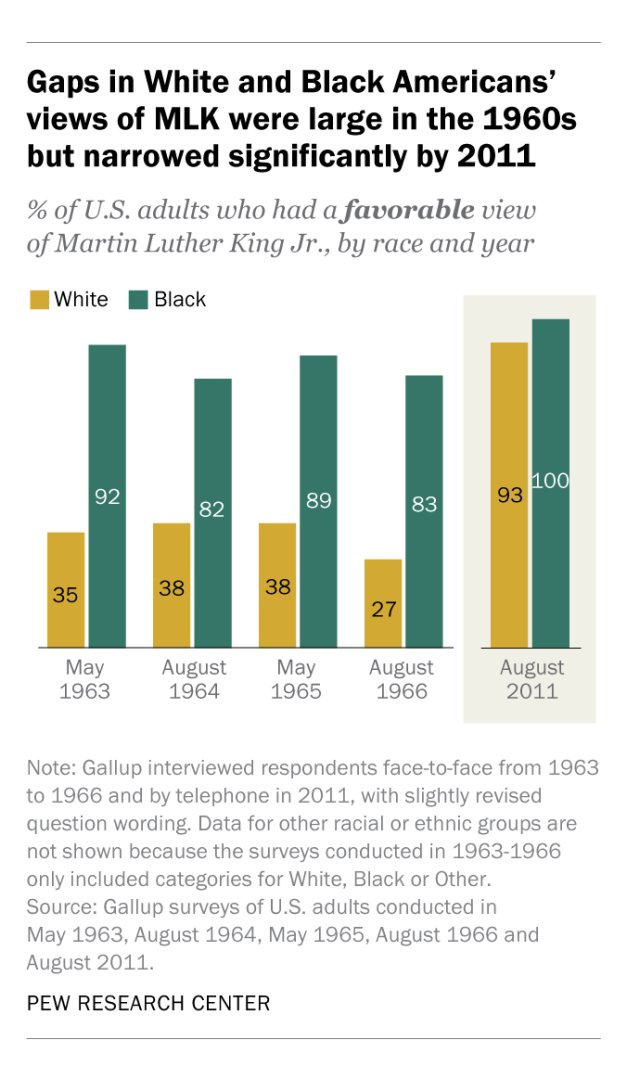

In general, nuclear cost overruns are driven by indirect costs, like having to hire more safety professionals due to added regulatory burdens.

Those explain 72% of the price hike in the U.S., 1976-87:

Those explain 72% of the price hike in the U.S., 1976-87:

In a more recent OECD report on nuclear from 2020, it was noted that "indirect cost[s] are the main driver of these cost overruns" and 80% of those indirect costs are attributable to largely unnecessary labor.

The regulatory costs levied against nuclear are so extreme that they can make components cost 50 times what they should, like in the case of 75 mm stainless steel gate valves.

The main factor differentiating nuclear and industrial grade? Unnecessary quality certification.

The main factor differentiating nuclear and industrial grade? Unnecessary quality certification.

The question is less "Why is nuclear expensive?" and more "Why is nuclear overregulated?"

And the reason isn't clear-cut. It's obvious it's not so simple as saying "ALARA!", since many countries manage positive learning despite sticking to the same philosophy.

And the reason isn't clear-cut. It's obvious it's not so simple as saying "ALARA!", since many countries manage positive learning despite sticking to the same philosophy.

It's more likely a combination of factors involving activism

Thanks to activism, the U.S. nuclear fleet won't achieve French emission levels because, under the Carter administration, activists managed to get reprocessing banned, tarring nuclear's reputation via the 'waste' issue

Thanks to activism, the U.S. nuclear fleet won't achieve French emission levels because, under the Carter administration, activists managed to get reprocessing banned, tarring nuclear's reputation via the 'waste' issue

In any case, nuclear remains a viable option for cleanly powering the future, and continued research into it is necessary for taking us into the stars.

Moreover, for consumers, it remains beneficial ($!) so long as intermittent forms of generation are, well, intermittent.

Moreover, for consumers, it remains beneficial ($!) so long as intermittent forms of generation are, well, intermittent.

There's more that can be said, but I'll cut it off there

Sources:

To read way more on this, check out this IFP piece:

And a Construction Physics favorite: oecd-nea.org/upload/docs/ap…

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

ifp.org/nuclear-power-…

construction-physics.com/p/why-are-nucl…

Sources:

To read way more on this, check out this IFP piece:

And a Construction Physics favorite: oecd-nea.org/upload/docs/ap…

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

ifp.org/nuclear-power-…

construction-physics.com/p/why-are-nucl…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh