Kenneth Clark lamented that civilization was a fragile thing.

He observed three “enemies” that could topple even the mightiest cultures—what are they?🧵

He observed three “enemies” that could topple even the mightiest cultures—what are they?🧵

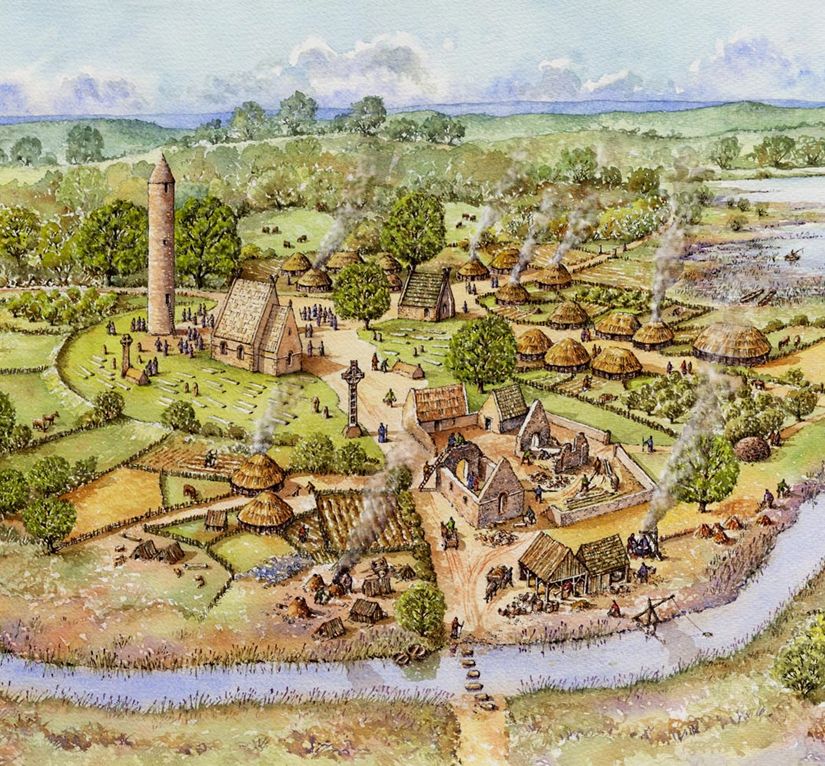

The first enemy is fear:

“fear of war, fear of invasion, fear of plague and famine, that make it simply not worthwhile constructing things, or planting trees or even planning next year’s crops. And fear of the supernatural, which means that you daren’t question anything.”

“fear of war, fear of invasion, fear of plague and famine, that make it simply not worthwhile constructing things, or planting trees or even planning next year’s crops. And fear of the supernatural, which means that you daren’t question anything.”

Fear paralyzes a people and stifles adventure, invention, and grand building projects.

Fear leads to stagnation.

Fear leads to stagnation.

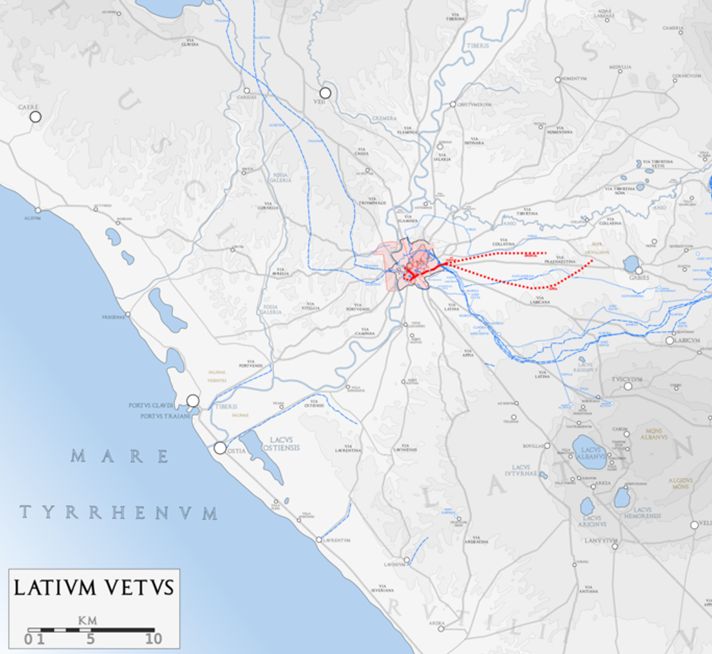

The second enemy is a lack of self confidence. Clark saw the late Roman empire as a prime example of a culture that didn’t believe in itself anymore:

“The late antique world was full of meaningless rituals, mystery religions, that destroyed self-confidence.”

“The late antique world was full of meaningless rituals, mystery religions, that destroyed self-confidence.”

When traditions and rituals lose their connection to what inspired them in the first place, they become the performance art of a dying civilization.

Cultures need to believe in something.

Cultures need to believe in something.

Finally, a civilization dies with exhaustion—the “feeling of hopelessness which can overtake people even with a high degree of material prosperity.”

Decadence, moral degradation, and lack of belief in something greater leave a society questioning the point of it all.

An aimlessness pervades society that is often only quenched by civilizational suicide.

An aimlessness pervades society that is often only quenched by civilizational suicide.

Clark tells a story by Greek poet Cavafy, in which he imagines an antique town that waits for barbarians to come and sack the city.

After a while, the barbarians move on and the city is spared. But the people are disappointed—destruction would have at least been interesting.

After a while, the barbarians move on and the city is spared. But the people are disappointed—destruction would have at least been interesting.

Enough doom and gloom—what’s the solution?

Clark draws a distinction between the “amenities” of civilization and the factors that caused it to prosper in the first place.

Clark draws a distinction between the “amenities” of civilization and the factors that caused it to prosper in the first place.

A society can be “dead and rigid” even while enjoying great wealth:

“People sometimes think that civilisation consists in fine sensibilities and good conversations and all that. These can be among the agreeable results of civilisation, but they are not what make a civilisation”

“People sometimes think that civilisation consists in fine sensibilities and good conversations and all that. These can be among the agreeable results of civilisation, but they are not what make a civilisation”

Ultimately Clark says that flourishing civilizations have two things beyond a base-level of material prosperity: confidence and belief.

“confidence in the society in which one lives, belief in its philosophy, belief in its laws, and confidence in one’s own mental powers.”

“confidence in the society in which one lives, belief in its philosophy, belief in its laws, and confidence in one’s own mental powers.”

For example, the way in which the stones of the Pont du Gard Aqueduct are laid shows not only a triumph of technical skill, but a vigorous belief in law and discipline, as well as a confidence in the ability to accomplish great tasks.

But there’s something else great civilizations share:

“Vigour, energy, vitality: all the civilisations—or civilising epochs—have had a weight of energy behind them,” Clark says.

“Vigour, energy, vitality: all the civilisations—or civilising epochs—have had a weight of energy behind them,” Clark says.

Clark’s thoughts on civilization should inspire reflection about our own. Does the West believe in its foundational principles, laws, or philosophy? Is the West confident in itself?

Or, is it fearful, timid, and exhausted?

Or, is it fearful, timid, and exhausted?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh