Aside from the fact that this guy sells online courses on how to get rich, I will explain why it's obvious from his clothes that he's not an aristocrat but rather a middle-class striver. 🧵

https://twitter.com/bayneframework/status/1776350601091121531

When I use the term "aristocrat," I'm referring to the ruling class in Europe with hereditary rank and titles. For the sake of this thread, I will mostly focus on Britain in the 19th and 20th centuries, as that's where we get most of our norms regarding classic men's style.

For much of history, men had their clothes made by tailors or women in their homes. Ready-made clothing was limited to slaves, miners, and sailors. That was until the mid-19th century, when ready-made clothes and shoes started coming out of the industrial revolution.

European aristocrats, however, continued to buy their clothes from bespoke tailors and shoemakers. In England, that typically meant going to Savile Row for suits, sport coats, and trousers; Jermyn Street for shirts; and various West End shops for shoes.

As I've mentioned before, men of this class had wardrobes divided between city and country. City (in this case, London) was where they did business in dark worsted suits and black oxfords. Country (often Scotland) was where they pursued sports in tweeds and brown derbies.

This is where we get the phrase "no brown in town." While the rule wasn't ironclad strict, it was a generally good guideline for understanding the TPO (time, place, occasion) for clothes and how to combine things to form an outfit. This is bc form followed function.

In an episode of The Crown, Margaret Thatcher visits the royal family at their Balmoral estate. Thatcher, who only knows how to dress for political life at 10 Downing Street, is very much out of her element in the Scottish countryside.

In one scene, she tags along with the family to go hunting. But she arrives in a delicate blue dress and black pumps while everyone else is in waxed hunting coats and thick boots. The clothes are more than clothes—they represent the cultural distance between her and the Queen.

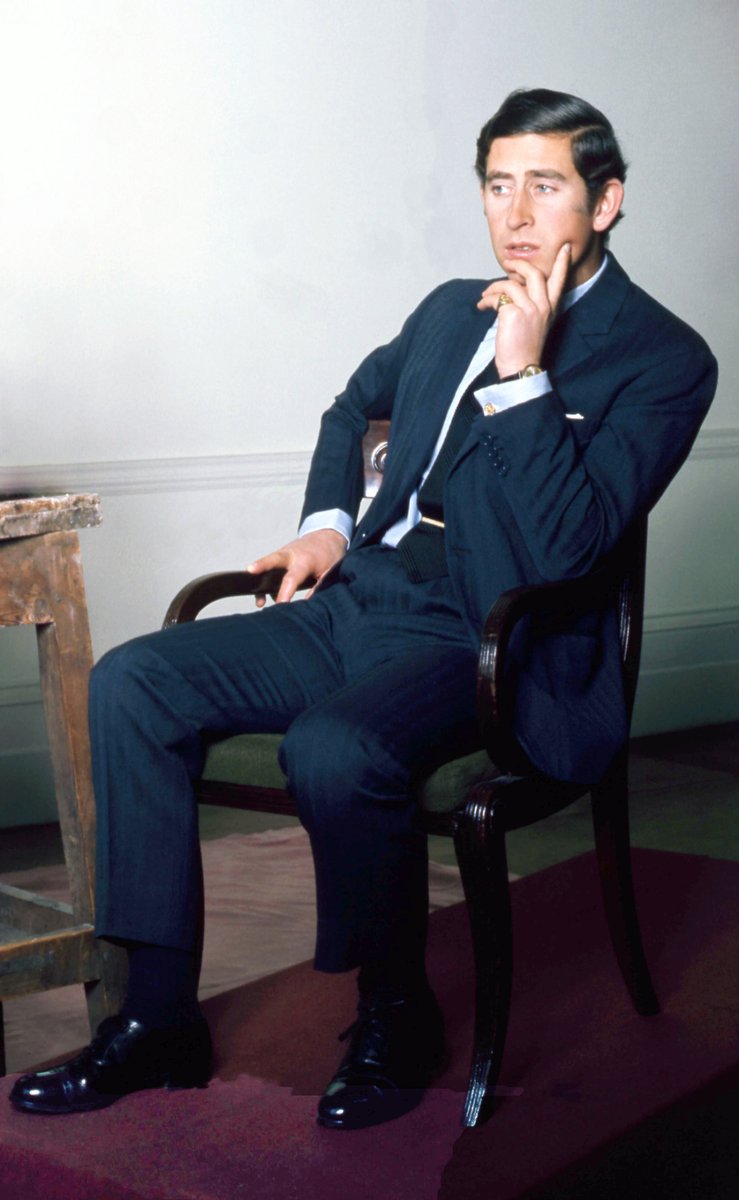

We can see this logic play out in the following two photos. Here, we see James Hamilton, 5th Duke of Abercorn, wearing a navy suit with a white shirt, silk tie, and a pair of black calfskin shoes. Everything here screams business: fine worsted wools, silk, navy, white, and black

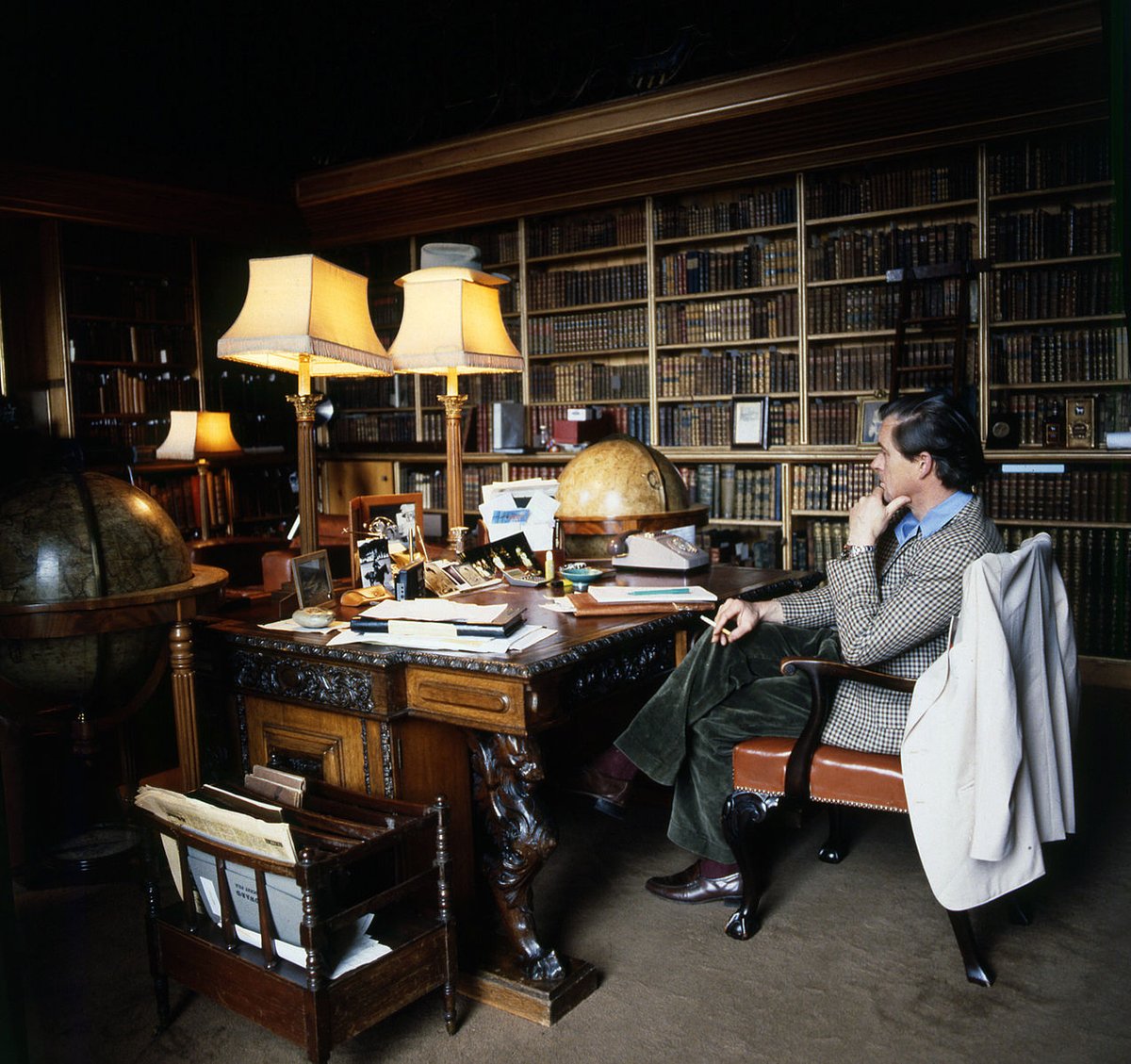

By contrast, here we see Ian Campbell, 12th Duke of Argyll, wearing more casual attire: brown checked tweed sport coat, corduroy trousers, light blue shirt, and brown loafers. Everything here says country: checks, tweeds, corduroy, blue, green, and brown

The 2nd thing has to do with cuts and proportions. While bespoke tailoring has changed over the years, the most traditional of tailors—those who would have served the aristocracy—stayed close to certain formulas. I can't list all the proportions but I will talk about shirts

I've already posted four aristocrats

1. Edward VIII, Duke of Windsor

2. Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

3. Hugh FitzRoy, 11th Duke of Grafton

4. James Hamilton, 5th Duke of Abercorn

1. Edward VIII, Duke of Windsor

2. Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

3. Hugh FitzRoy, 11th Duke of Grafton

4. James Hamilton, 5th Duke of Abercorn

Zoom in, and you will see one thing in common: they are all wearing shirt collars with points that are long enough to tuck under their jacket's lapels.

100+ years after the Duke of Windsor, we see this in other European royals as well. This is the most classic proportion.

100+ years after the Duke of Windsor, we see this in other European royals as well. This is the most classic proportion.

Finally, a historical fact about ties. Remember that traditional British dress was governed by time, place, and occasion (this was the distinction between city and country). Regimental striped ties were also a sign of belonging to some organization, like school or the military.

This can be a sensitive thing in the UK. The tie below signals that the wearer is part of The Rifles, an infantry regiment of the British Army. You would presumably not wear it unless you were a member.

Not wanting to be accused of stealing valor, Brooks Brothers introduced the American regimental stripe in 1902, which reversed the British "heart to sword" stripe direction. Notice the US stripes running in the other direction below. This is Brooks Bros No. 1 and 2 Rep ties

Now that we know a little about British aristocratic men's dress, let's look at why it's obvious the original poster is not an aristocrat.

First, he's not only wearing a brown belt with a dark worsted suit, but he's wearing a tan belt. We can presume this means he's either wearing tan shoes or his belt doesn't match his shoes. Neither of which is something an aristocrat would ever do, as tan is a casual color

Secondly, his collar points don't reach his lapels. This is a strong indication his shirt is ready-to-wear, not bespoke. And since it's 2024, the shirt is likely a cheap downmarket version of early 2000 trends (as influenced by Thom Browne, Rag & Bone, and Band of Outsiders)

Finally, he's wearing an American striped tie, and we don't have aristocrats in the United States. This is the ersatz version of the true aristocrat's tie, which has stripes running in the other direction and in colors indicating the wearer's membership in some organization.

Other things give it away, such as his low-rise trousers (which again, indicate he's likely wearing cheap ready-to-wear that's downmarket of early 2000s trends). All indicators point to a striver who wants to look rich but isn't familiar enough with the look to get it right.

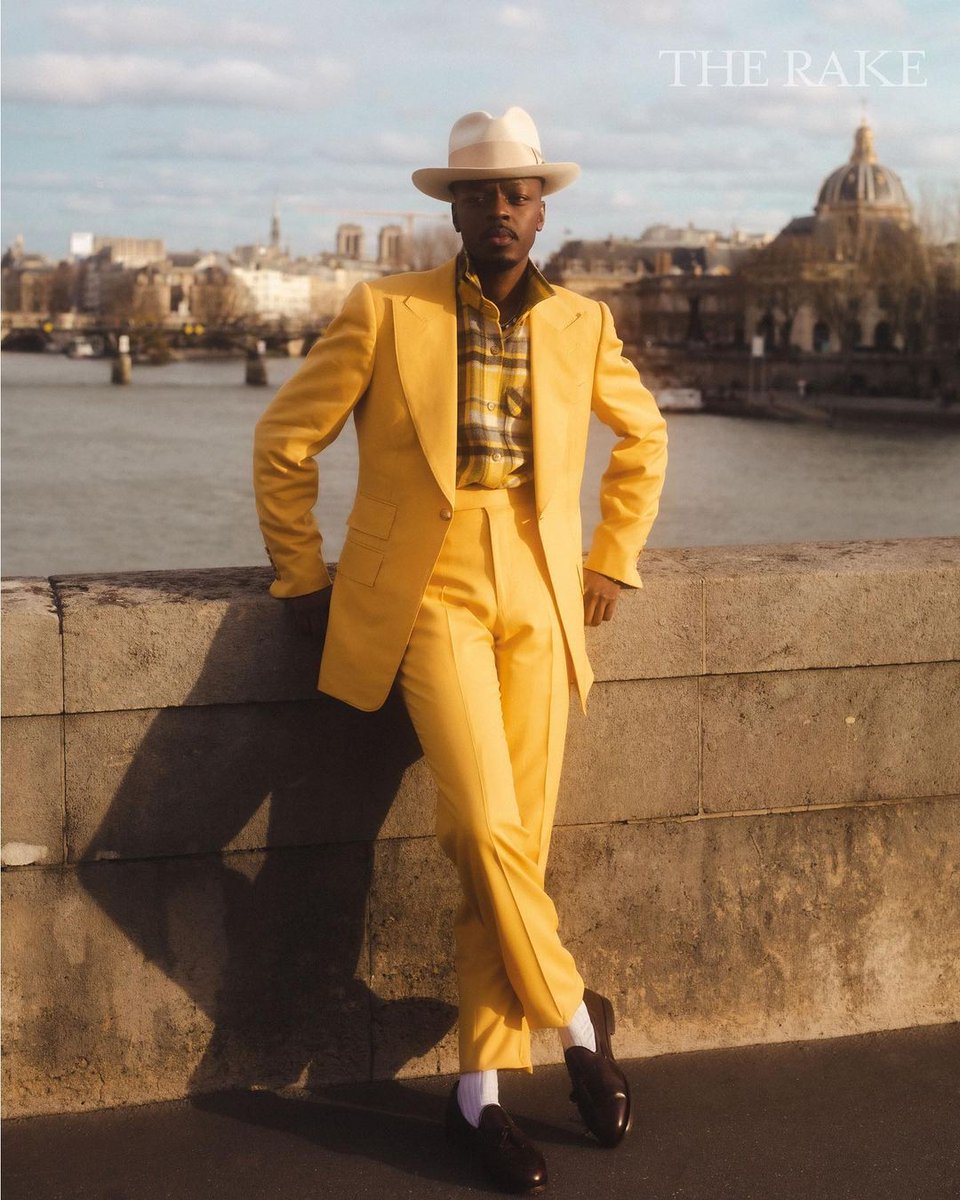

I should add there's nothing wrong with not dressing like an aristocrat. There are many grand traditions, even in tailoring, that are tremendously stylish and have nothing to do with British royals (e.g. Tommy Nutter, Edward Sexton). Am just saying it's obvs he's not aristo

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh