That so many people buy into this reflects:

(i) how we as a country are now so far removed from manufacturing that we understand so little of it (as demonstrated here and many similar replies), and

(ii) the difference between ideas and execution.

(i) how we as a country are now so far removed from manufacturing that we understand so little of it (as demonstrated here and many similar replies), and

(ii) the difference between ideas and execution.

https://twitter.com/noahpinion/status/1777124504910873036

As an early EV pioneer, Tesla had an interesting idea which was to “diecast” a much larger metal chassis instead of welding together multiple pieces as had been traditionally done.

This is related in part to the re-design of the chassis around a large battery pack.

This is related in part to the re-design of the chassis around a large battery pack.

One problem was nobody had a diecasting machine large enough to cast such a large piece, only smaller ones for smaller pieces.

These larger machines didn’t exist not because of reasons of technical feasibility but because nobody had asked for it before.

These larger machines didn’t exist not because of reasons of technical feasibility but because nobody had asked for it before.

Diecasting has been around for two centuries.

Historically producers of diecasting machines were relatively small businesses, often family run, linked to industrial and manufacturing supply chains and producing only a handful of these machines on a custom basis every year.

Historically producers of diecasting machines were relatively small businesses, often family run, linked to industrial and manufacturing supply chains and producing only a handful of these machines on a custom basis every year.

As the manufacturing base grew in China, Chinese diecasting manufacturers like Hai’tian became the largest players in this space by mass-producing more standardized versions of these machines for less cost and gaining market share from the small family run businesses.

The smaller family-run businesses like L.K. or Chen Hsong (on the plastic injection molding side) differentiated by leaning more into customization and away from the larger mass market.

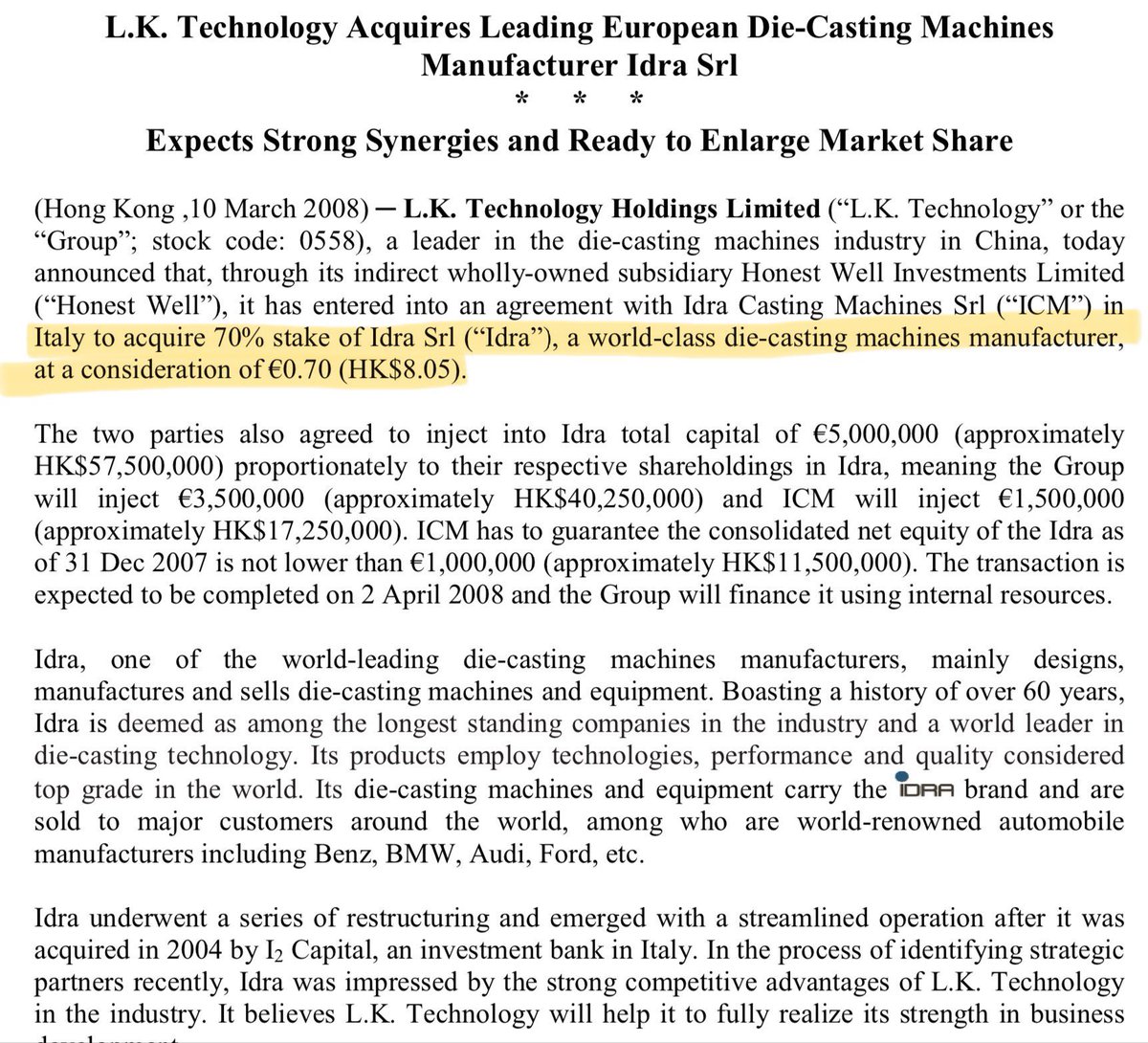

Some like Idra Group in Italy ran into financial trouble and needed bailouts.

Some like Idra Group in Italy ran into financial trouble and needed bailouts.

https://twitter.com/glennluk/status/1773371424033452242

In 2008, LK acquired Idra Group for exactly €1 plus a modest capital injection.

It was effectively a bailout for the struggling Italian business.

It was effectively a bailout for the struggling Italian business.

A decade or so later, Tesla would turn to LK and Idra Group because it wanted larger, *custom-built diecasting machines and LK/Idra specialized in custom-built machines.

Always the masterful marketer, it dubbed them “Gigapresses”.

Always the masterful marketer, it dubbed them “Gigapresses”.

People seem to think these “Gigapresses” are some proprietary technology breakthrough.

But anyone who knows this industry would instinctively understand that this is not some newfangled technology with secret IP.

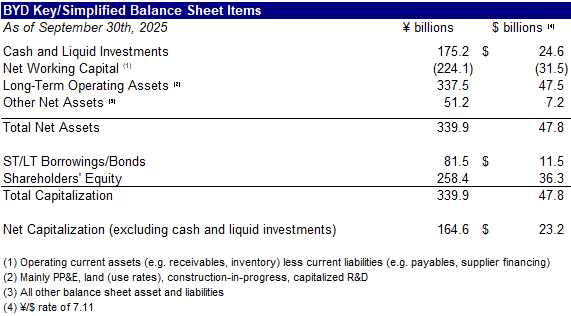

LK’s entire annual R&D budget is HK127 million ($15 million).

But anyone who knows this industry would instinctively understand that this is not some newfangled technology with secret IP.

LK’s entire annual R&D budget is HK127 million ($15 million).

As soon as market demand was proven out for it, industry leaders like Hai’tian Int’l (Precision division) started producing more standardized versions of them, including for Xiaomi on its recent SU7 release.

These cliched narratives about China and how it can only copy are a dangerously misleading mindset that distracts from the core issues at the root of American manufacturing decline.

First, ideas mean little in manufacturing if you cannot execute.

And it’s Chinese players like Hai’tian that have the most accumulated technical expertise and human capital in the machinery space.

And it’s Chinese players like Hai’tian that have the most accumulated technical expertise and human capital in the machinery space.

It’s quite a leap to accuse/insinuate “China” of co-opting technology in a space that is led by Chinese players that are doing the execution.

It reflects the sad state of understanding in this country of how things these days are *physically produced.

It reflects the sad state of understanding in this country of how things these days are *physically produced.

Second, diecasting is only one of many upstream machines, equipment and robotics that are needed in the manufacturing process.

Being able to produce a world-class chassis is not a competitive differentiator, represent <5% of the cost of a typical baseline vehicle.

Being able to produce a world-class chassis is not a competitive differentiator, represent <5% of the cost of a typical baseline vehicle.

There are far more important sources of manufacturing differentiation with modern robotics and equipment used elsewhere on the factory line.

More importantly “digital native” advanced manufacturing is about how all of it integrates together with software and real-time data.

More importantly “digital native” advanced manufacturing is about how all of it integrates together with software and real-time data.

https://twitter.com/glennluk/status/1776627077720010968

And the sad reality is that Chinese industrial equipment suppliers like Shenzhen Innovance now lead or will soon lead in almost all of these upstream sectors.

This is very analogous to how American, Japanese and European players dominate upstream semi capex.

This is very analogous to how American, Japanese and European players dominate upstream semi capex.

That is the core issue here. Chinese can execute in these types of manufacturing, America is behind,

Tesla simply cannot turn many innovative ideas into mass-produced product as efficiently without turning to Chinese manufacturing and upstream machines suppliers.

Tesla simply cannot turn many innovative ideas into mass-produced product as efficiently without turning to Chinese manufacturing and upstream machines suppliers.

And the harsh reality is that America/RoW is farther behind China on this front than China is behind the bleeding-edge on semi capex.

And while China is making progress catching up on the latter, America is making painfully slow progress on the former.

And while China is making progress catching up on the latter, America is making painfully slow progress on the former.

It’s very dangerous to ignore this harsh reality by continuously underestimating China’s capabilities by attributing everything to old tropes.

The sooner we face it and start focusing on the core domestic issues instead of tilting at imaginary windmills, the better.

The sooner we face it and start focusing on the core domestic issues instead of tilting at imaginary windmills, the better.

https://twitter.com/glennluk/status/1775511883442749632

A very current example: we need to build up solar and battery manufacturing in this country.

Chinese firms hold most of the specialized manufacturing IP, including specialized line equipment needed to produce these economically.

Chinese firms hold most of the specialized manufacturing IP, including specialized line equipment needed to produce these economically.

Is spending time/energy propagating these old tropes really the most mature approach?

Over what? Chassis & technology that has been around for centuries?

Does it further the goal of build out onshore solar/battery production that isn’t 2-3x more expensive than global levels?

Over what? Chassis & technology that has been around for centuries?

Does it further the goal of build out onshore solar/battery production that isn’t 2-3x more expensive than global levels?

Hoopla over these diecasting machines reminds me a bit of the hoopla over shipbuilding.

We did not lose our machine tools industries recently to China.

Like shipbuilding, we lost them 4-5 decades ago before China's rise👇 (report was published in '94)

rand.org/pubs/research_…

We did not lose our machine tools industries recently to China.

Like shipbuilding, we lost them 4-5 decades ago before China's rise👇 (report was published in '94)

rand.org/pubs/research_…

Tesla and @elonmusk understand all of this more than any American manufacturer today: that the key to success is running faster than the competition.

It has been one of the few American companies to make the leap into advanced manufacturing, and it did it in “ludicrous mode”.

It has been one of the few American companies to make the leap into advanced manufacturing, and it did it in “ludicrous mode”.

@elonmusk There is unlikely to be a single ounce of regret for building Shanghai Gigafactory and entering China.

Tesla has yet another advantage over its domestic competition that does not have such tight integration into China’s EV supply chain.

Tesla has yet another advantage over its domestic competition that does not have such tight integration into China’s EV supply chain.

Although Tesla has certainly come up with great ideas over the years, what really got it to this point today was hardcore execution.

There is a long road ahead to build adv. mfg. critical mass + supply chains in this country and Tesla is showing us a path on how to get it done.

There is a long road ahead to build adv. mfg. critical mass + supply chains in this country and Tesla is showing us a path on how to get it done.

P.S. Re-read the original source tweet by @kyleichan with all of the above in mind.

What Kyle is saying here is *very different from what the subsequent quote-tweet was saying. He understands the nature of IP in the machine tools industry.

What Kyle is saying here is *very different from what the subsequent quote-tweet was saying. He understands the nature of IP in the machine tools industry.

https://twitter.com/kyleichan/status/1777072166149714304

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh