NYC, 1930s (colorized)

Have you ever felt that the average person dressed better in the past? IMO, the reason has nothing to do with respectability, body shape, or even suits.

It has to do with the loss of what I call "shape and drape." 🧵

Have you ever felt that the average person dressed better in the past? IMO, the reason has nothing to do with respectability, body shape, or even suits.

It has to do with the loss of what I call "shape and drape." 🧵

Let's start with some definitions. The term shape refers to silhouette, which is the shape of our clothes when we remove all the details (i.e., the outfit's outline). Notice that Hepburn's outfits have a distinctive shape that's not just her human form.

In this thread, the term "drape" refers to how the fabric hangs and moves. In most cases—although not always—you want the fabric to hang cleanly, that is, without puckering, pulling, or wrinkling (although later, we'll see this is complicated). Drape also refers to movement.

When people admire fashions of the past, they often bring up issues unrelated to clothes (e.g., respectability, politics, body type). What they're actually admiring are the shapes of these clothes and how they drape. Notice the procession of wonderful shapes here:

In the last twenty years, we've lost the concept of "shape and drape" for three reasons.

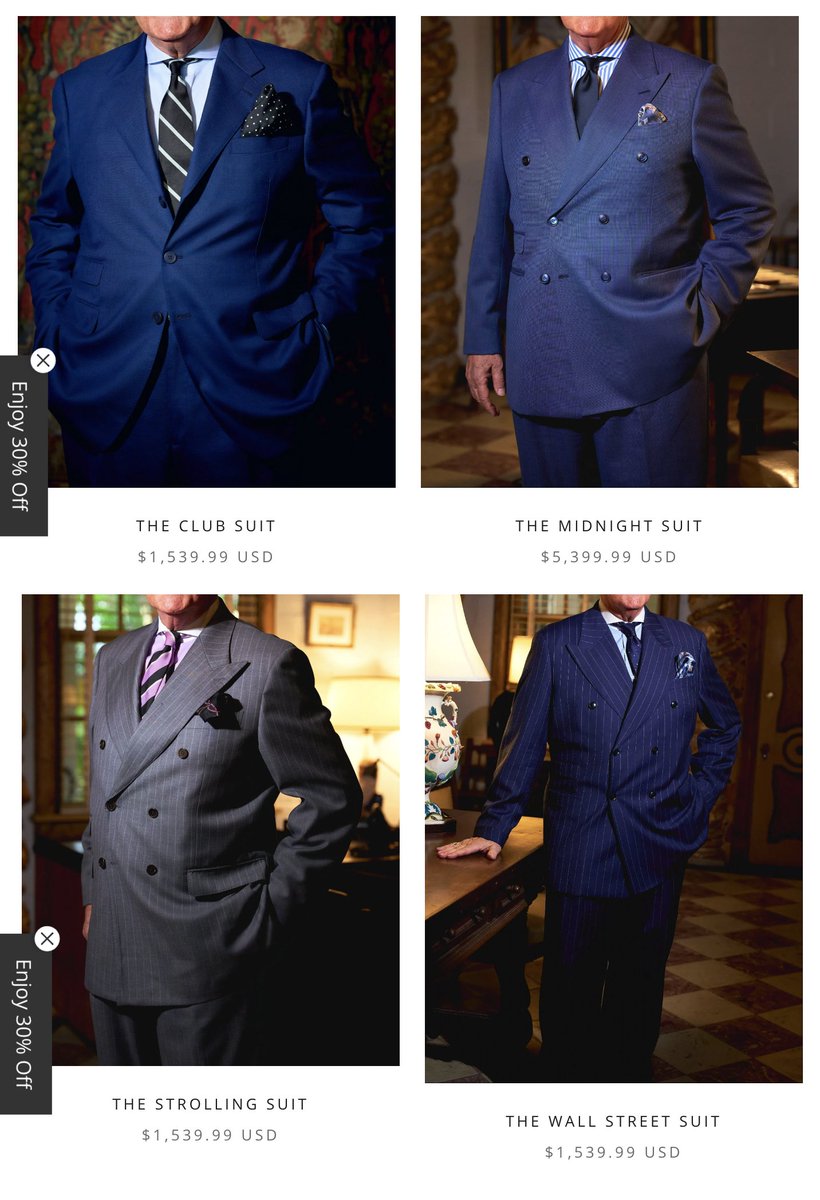

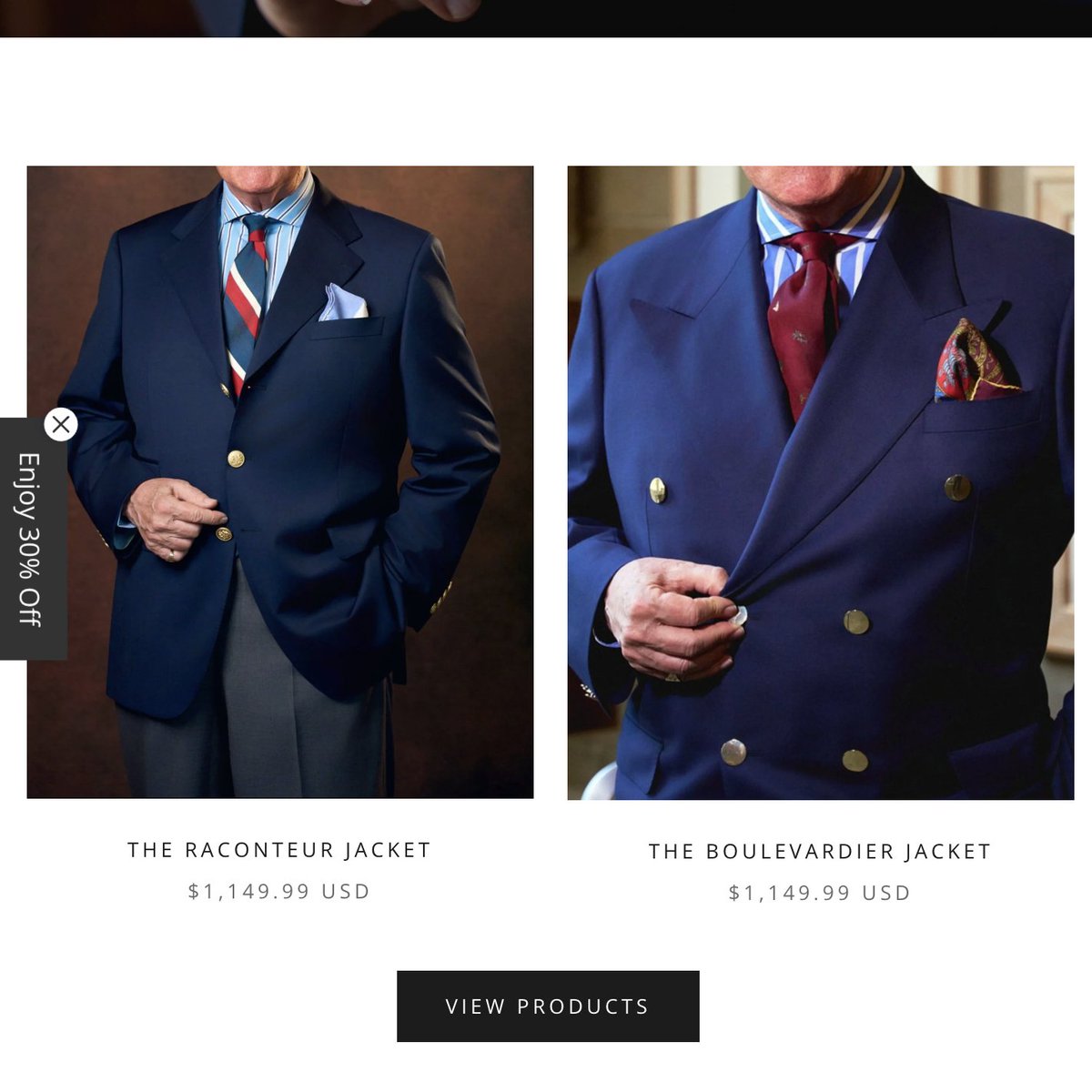

1. The simplification of clothing. While this thread is not saying that everyone has to wear a suit, I will use suits to illustrate a point.

1. The simplification of clothing. While this thread is not saying that everyone has to wear a suit, I will use suits to illustrate a point.

As I've mentioned in other threads, suits and sport coats are unique in that they're built up from layers of haircloth, canvas, and padding, which are carefully sewn together using techniques such as pad stitching, darts, and wedges to create three-dimensional shapes.

By contrast, much modern clothing is very simple. A T-shirt is just four panels and a collar sewn together with some seams and no inner construction. Most button-up shirts are not that different. Outerwear might be a fleece vest.

2. Everything now is slim-fit. The push towards slim fit has removed the ability for clothes to have their own shape, as they now just recreate the lines of your body. If the clothes are too tight, they'll also not drape well (e.g., buckling, pulling, collar gaps).

3. Removal of jackets. Finally, when people admire fashion in the past, they are often looking at how clothes were worn in the distant past (say, early to mid-20th century) in certain fashionable locales (e.g., London, Paris, NYC)

Since this was before the widespread adoption of central heating, most people at this time wore jackets, even when indoors. They also wore clothes made from much heavier fabrics. It was not unusual for a man to wear a suit made from 18oz wool (today, it would be like 10oz).

However, as time has gone on, people have increasingly worn lightweight clothes (which don't drape as well), slim-fit clothes (which have no shape), and shed layers (no jackets). The most common uniform is some kind of button-up shirt or T-shirt with jeans, chinos, or shorts.

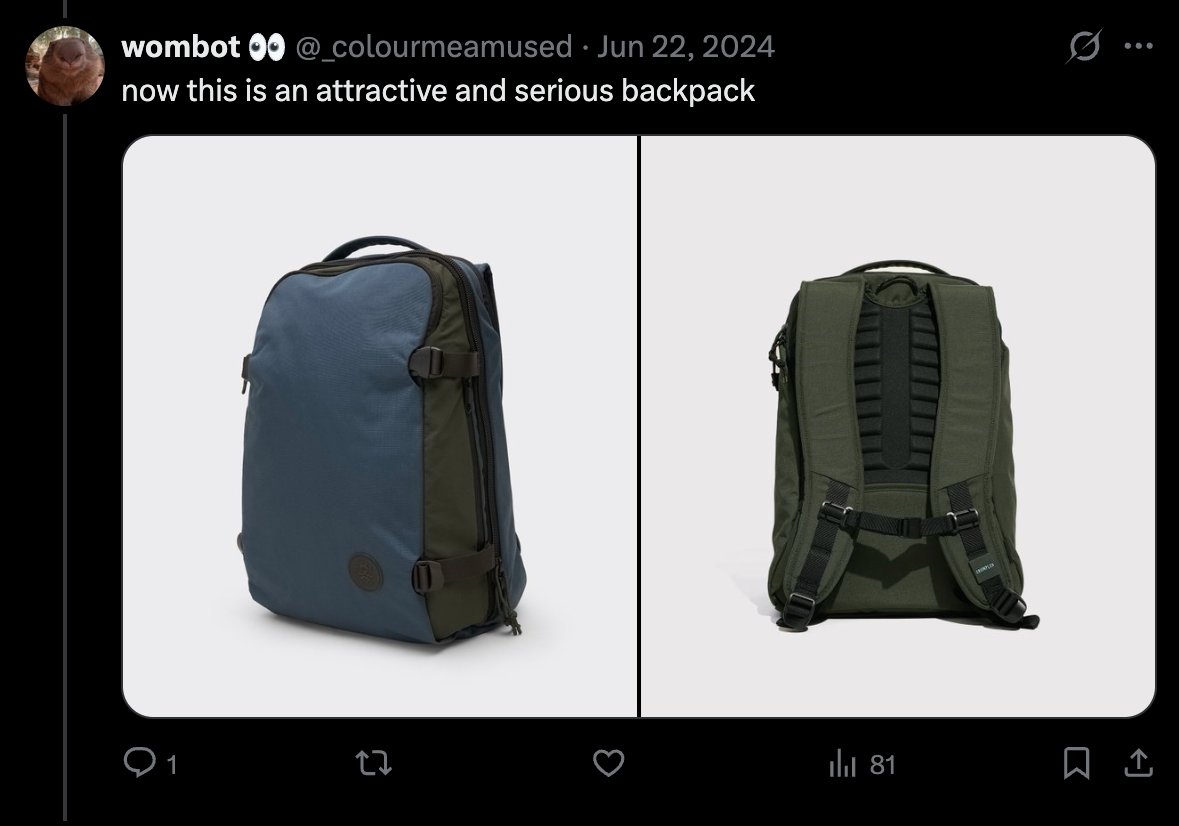

Even the designs of our outermost layers have become simplified. Let's look at some comparisons.

Left: Slim bomber with shoulder seam sitting on shoulder joints. Jacket conforms to wearer's body shape.

Right: Big bomber with dropped shoulder seams. Jacket has a round shape.

Left: Slim bomber with shoulder seam sitting on shoulder joints. Jacket conforms to wearer's body shape.

Right: Big bomber with dropped shoulder seams. Jacket has a round shape.

Left: Slim-fit sweater has a silhouette similar to the bomber above. It's just the wearer's body.

Right: This baggier sweater has dropped shoulder seams and fuller sleeves. This is not the same shape as the wearer's body.

Right: This baggier sweater has dropped shoulder seams and fuller sleeves. This is not the same shape as the wearer's body.

Left: Is this silhouette starting to look familiar? It's the same rectangle as everything above.

Right: This roomier, longer coat has enough space for movement. It swishes when you walk. Has a glorious flow. There's shape and drape!

Right: This roomier, longer coat has enough space for movement. It swishes when you walk. Has a glorious flow. There's shape and drape!

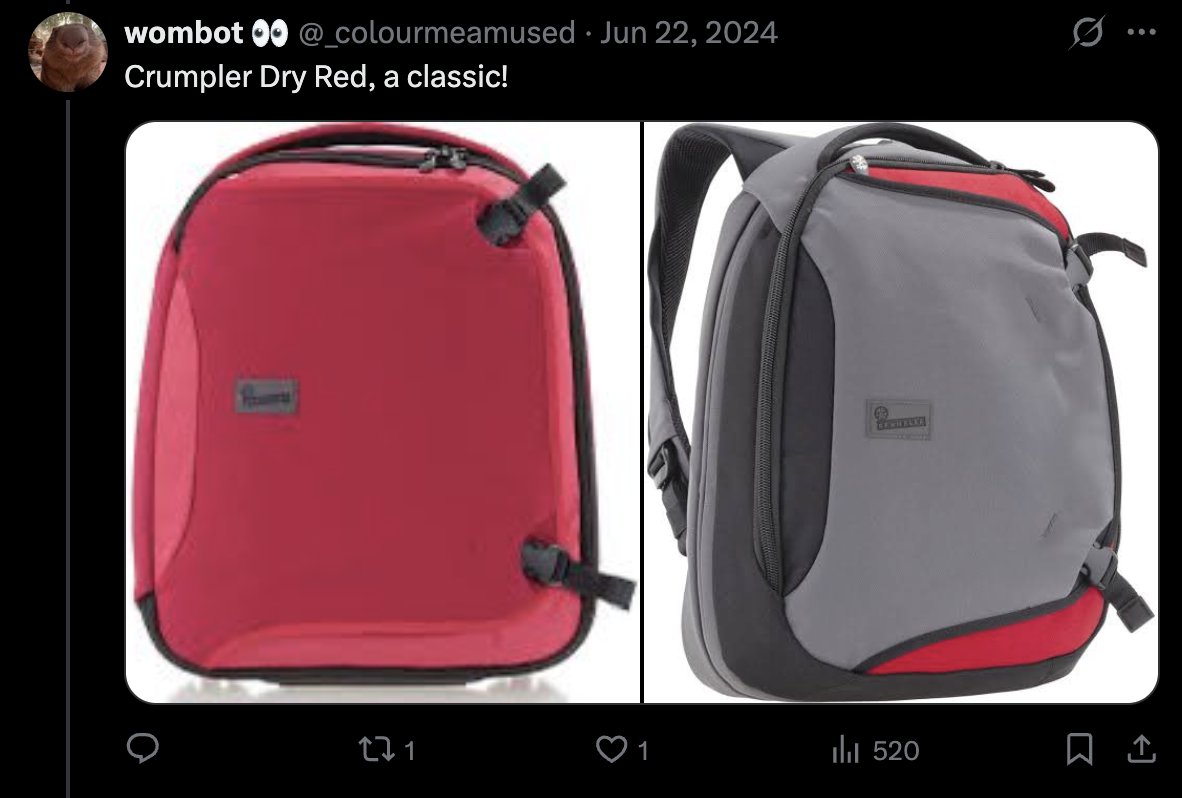

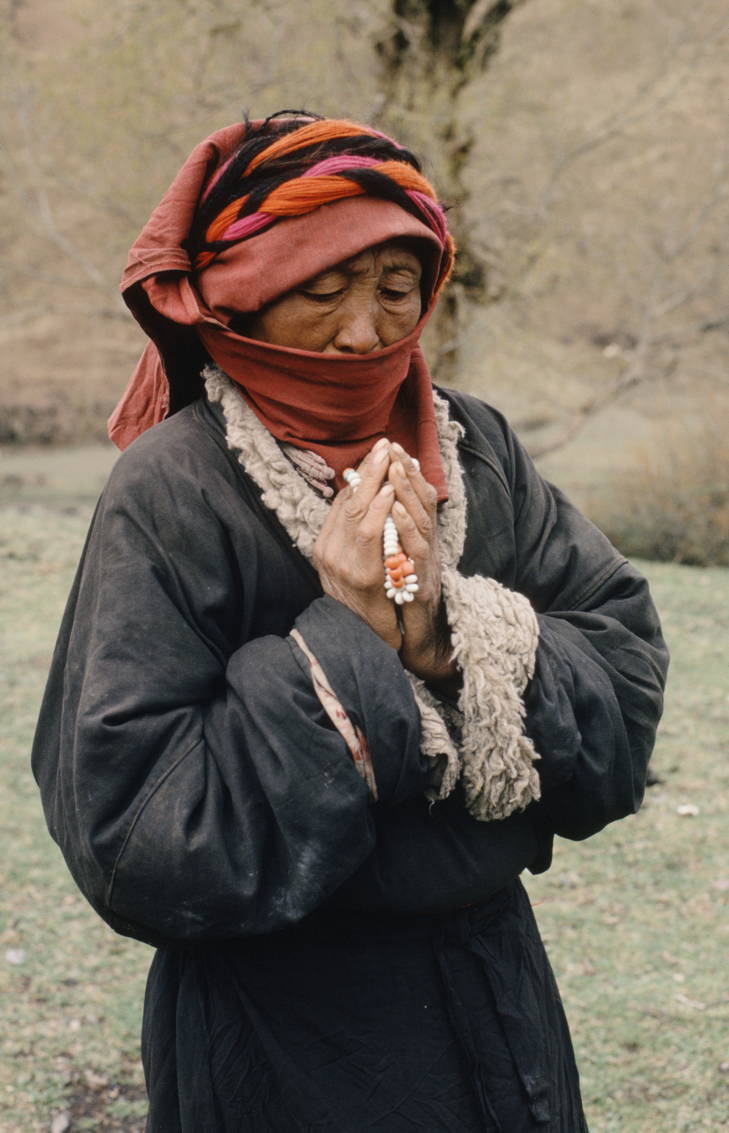

When people admire an outfit, they often consider its shape and drape without knowing it. Look at these early photographs of Arab men, taken during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. There is so much shape and drape!

Look at these more contemporary examples of non-Western attire. I think when people see the first photo, their reaction is, "Wow, look at that cool color!" But a slim yellow T-shirt worn with slim yellow chinos would not have the same effect bc the outfit would not have shape.

So far, I've used the term drape to refer to how the fabric should hang cleanly or move beautifully. We see this in the two photos below. The nylon pants on the left are wrinkly (thus, they don't drape cleanly). On the right, we see a cleaner line (good drape).

But drape can be a bit more nuanced. Here, we see a black Hanes T-shirt next to a black Rick Owens T-shirt. A bad reaction would be, "I don't like my shirts wrinkled." However, this effect matches Rick Owens' aesthetic. The fabric drapes well in that regard.

In fact, avant-garde designers such as Rick Owens and Yohji Yamamoto are all about shape and drape because they're masters at forcing fabrics to take on new, distinctive silhouettes and draping in beautiful, controlled ways.

Similarly, @modsiwW's outfits are great because they're so distinctive in terms of shape. Look at the way each of these outfits plays with proportions, volume, and silhouette.

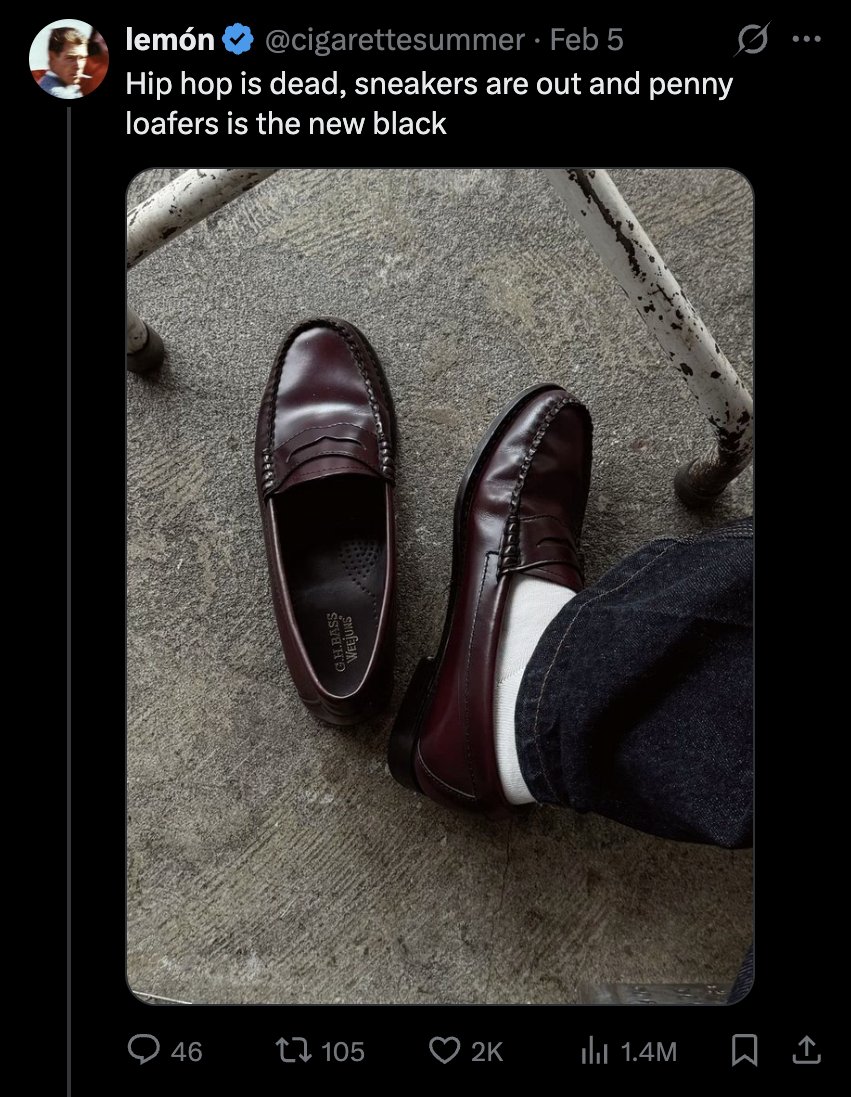

Sometimes, I see stuff like this online, where someone has a very clinical view about how all clothes should fit. Slim fit = good; baggy = bad. This view strips context, culture, and tailoring techniques from clothes.

IMO, this extremely limited understanding of fashion is a contributing factor to some of the body obsessions on Twitter. Of course, if you insist that all clothes be slim-fit, then you may feel pressured to have a certain body. You don't allow your clothes to have shape!

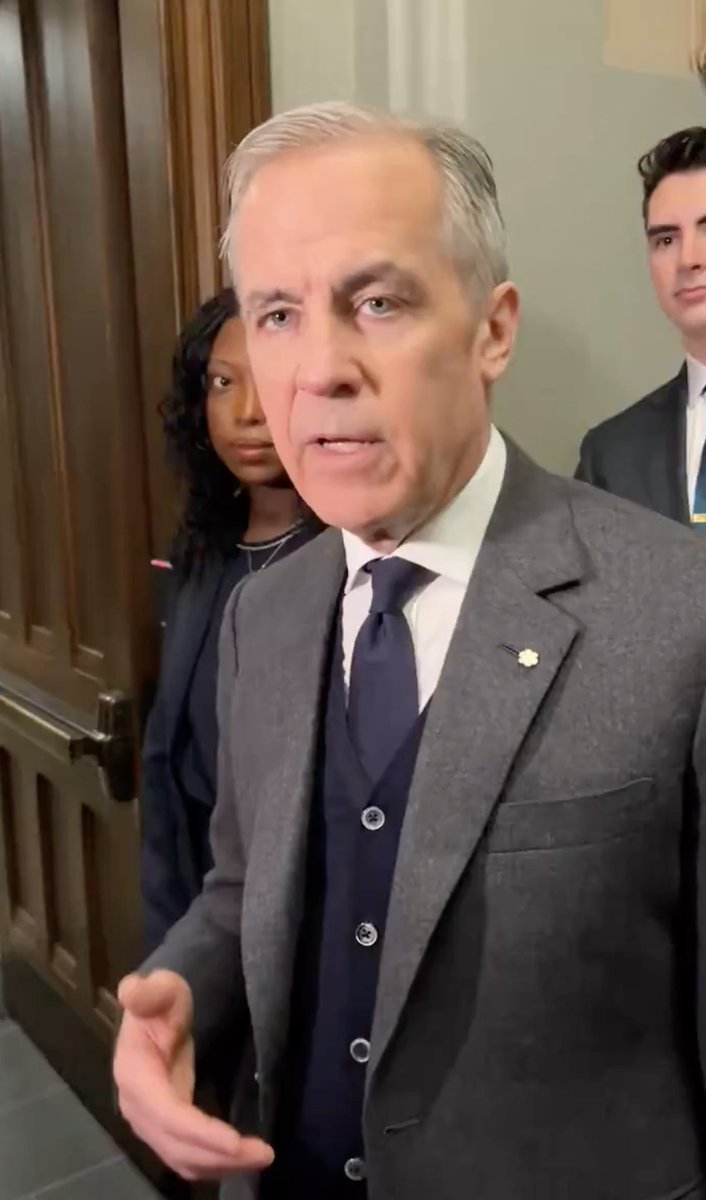

But here we see that even athletic body types look great when the person is wearing something with shape and drape. The shapes of these clothes are not the same as the wearer's body. The tailoring is also done well, which comes across in how the fabric drapes.

Even with very simple outfits, such as button-up shirts and shorts, we can see how allowing the item to take on a more distinctive shape—maybe a wider body or sleeve, or playing with hemlines or pockets—can result in a more interesting outfit.

In summary:

1. Try to wear a jacket. Or find ways to layer

2. Pay attention to the complex construction of clothes

3. Don't assume everything has to be slim-fit

4. Think about outfits as shapes

5. Pay attention to how fabric drapes

IMO, that's what ppl admire in good outfits

1. Try to wear a jacket. Or find ways to layer

2. Pay attention to the complex construction of clothes

3. Don't assume everything has to be slim-fit

4. Think about outfits as shapes

5. Pay attention to how fabric drapes

IMO, that's what ppl admire in good outfits

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh