Most cultural movements aren’t grass roots—they’re top down.

Charlemagne’s cultural rebirth, the “Carolingian renaissance,” proved how real cultural change is planned and executed by society’s elites…🧵

Charlemagne’s cultural rebirth, the “Carolingian renaissance,” proved how real cultural change is planned and executed by society’s elites…🧵

In the late 8th and early 9th century, Charlemagne ruled vast lands from Northern Spain to the North Sea.

Charlemagne was a skilled administrator, but his newfound empire had problems.

Charlemagne was a skilled administrator, but his newfound empire had problems.

Though the empire was flourishing economically—driven in part by a slave trade created by Charlemagne’s conquests—the centuries since Rome’s fall took a toll on the cultural development of the West.

Latin literacy was falling, a blow to the administrative and scholarly classes since Latin was essential for empire-wide communication.

Likewise, an uneducated clergy had difficulty interpreting and preaching on the Vulgate Bible, the universal biblical translation of the time.

Likewise, an uneducated clergy had difficulty interpreting and preaching on the Vulgate Bible, the universal biblical translation of the time.

On an aesthetic level, there were no cohesive architectural or artistic styles that marked his lands as a bonafide empire—empires needed grand building projects and beautiful art.

In short, the Frankish Kingdom wasn’t the beacon of culture that Charlemagne wanted it to be.

In short, the Frankish Kingdom wasn’t the beacon of culture that Charlemagne wanted it to be.

He devised a plan to create a “cultural rebirth.” He looked to ages past—to the high cultures of Greece and Rome—as models.

No scholar or artist himself, he needed to gather the brightest minds to pull off his cultural rejuvenation.

No scholar or artist himself, he needed to gather the brightest minds to pull off his cultural rejuvenation.

He brought in scholars from all across Europe: Peter of Pisa, a grammarian and poet, became Charlemagne’s Latin tutor; Paulinus of Aquileia, a prominent theologian, spearheaded the “Christianization” of the empire; and Paul the Deacon became the kingdom’s most eminent historian.

But the main architect behind Charlemagne's new renaissance was undoubtedly Alcuin of York, who was described in Einhard’s Vita Karoli Magni (Life of Charlemagne) as “The most learned man anywhere to be found."

Alcuin became one of the king’s closest advisors.

Alcuin became one of the king’s closest advisors.

A British scholar and cleric, he saw himself as sowing seeds for a brighter future through education:

“In the morning, at the height of my powers, I sowed the seed in Britain, now in the evening when my blood is growing cold I am still sowing in France, hoping both will grow.”

“In the morning, at the height of my powers, I sowed the seed in Britain, now in the evening when my blood is growing cold I am still sowing in France, hoping both will grow.”

Two documents penned by Alcuin, the “Admonitio Generalis” and “De Litteris Colendis,” laid out Charlemagne’s plan of enculturation. His task was twofold:

-Christianize the kingdom by reforming/disciplining the clergy

-Educational reform through the establishment of new schools

-Christianize the kingdom by reforming/disciplining the clergy

-Educational reform through the establishment of new schools

Culture, Charlemagne envisioned, would flow downstream from a religious and educated court literati—the “intellectual” class. It was a rigidly top-down approach.

And for the most part, it worked.

And for the most part, it worked.

Religious texts were made more accessible, deepening Christianity’s foothold throughout the kingdom.

Schools taught religious music, singing, and psalms which encouraged the spread of the faith, and a focus on grammar made it so religious texts could be revised and edited.

Schools taught religious music, singing, and psalms which encouraged the spread of the faith, and a focus on grammar made it so religious texts could be revised and edited.

There was an overall increase in literature, law, music, architecture, visual art, and liturgical reforms.

Newly established schools became effective centers of education, and new editions and copies of classic works, both Christian and pagan, were produced.

Newly established schools became effective centers of education, and new editions and copies of classic works, both Christian and pagan, were produced.

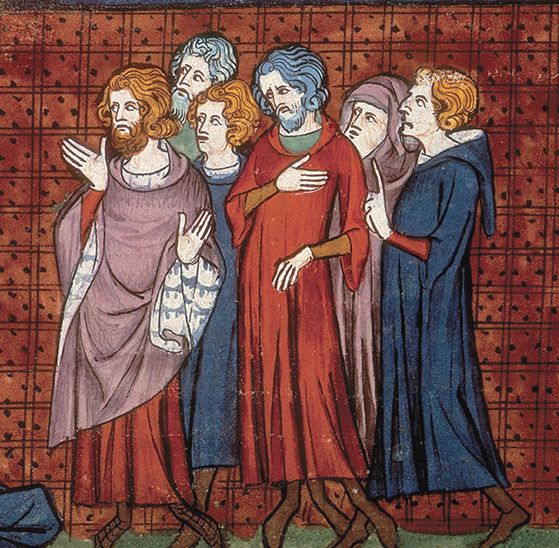

A new style of art emerged; a unique blend of classical mediterranean art forms and northern elements came to be known as “Carolingian Art.”

Defined by a lavish and dignified style, it was a precursor to Romanesque and Gothic art that later dominated Europe.

Defined by a lavish and dignified style, it was a precursor to Romanesque and Gothic art that later dominated Europe.

Illumination and ornate metalwork adorned manuscripts while frescoes and mosaics became popular in Churches and palaces.

Christian imagery was a recurring theme in Carolingian art—a visual reminder of Charlemagne’s mission to create a unified Christian empire.

Christian imagery was a recurring theme in Carolingian art—a visual reminder of Charlemagne’s mission to create a unified Christian empire.

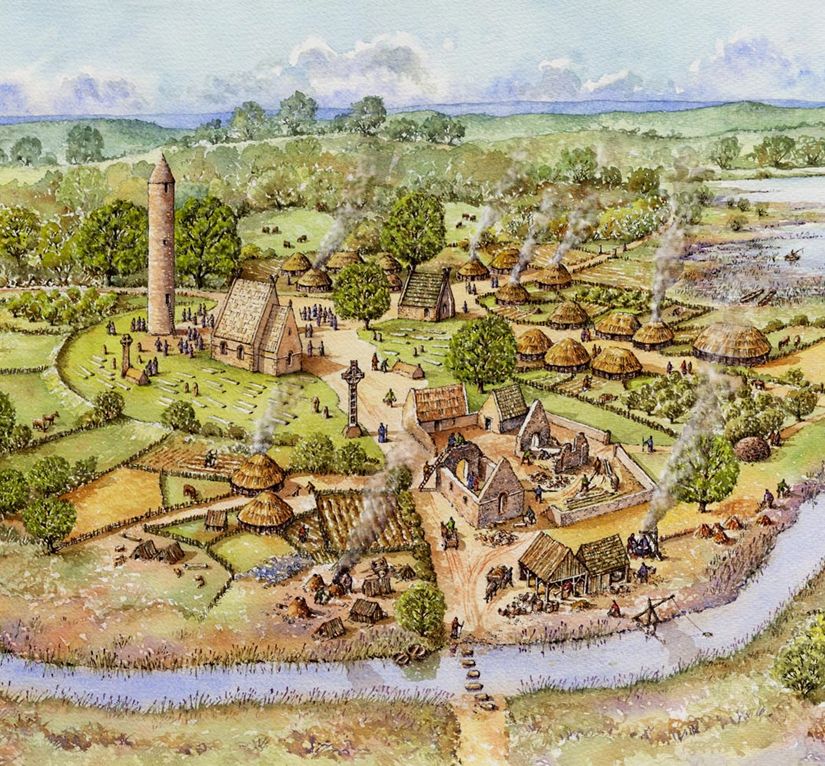

Architectural projects also boomed during the Carolingian period.

Between 768 and 855, a whopping 27 new cathedrals, 417 monastic buildings and 100 royal residences were built. During Charlemagne's reign alone, 16 cathedrals, 232 monasteries and 65 palaces were constructed.

Between 768 and 855, a whopping 27 new cathedrals, 417 monastic buildings and 100 royal residences were built. During Charlemagne's reign alone, 16 cathedrals, 232 monasteries and 65 palaces were constructed.

Lost building techniques were incorporated into new projects. An ancient architectural treatise written by Vitruvius was found, providing a template for stone-building techniques.

Thus, new stone structures were built in northern Europe for the first time since Rome’s presence.

Thus, new stone structures were built in northern Europe for the first time since Rome’s presence.

Roman basilicas and triumphal arches were used as templates for Carolingian buildings, though the Franks put their own twist on them.

The Palatine Chapel at Aachen reflects late Roman building techniques with its vaults and arches.

The Palatine Chapel at Aachen reflects late Roman building techniques with its vaults and arches.

Charlemagne’s efforts to revitalize the Church and educational institutions had a lasting effect, producing countless scholars and theologians.

Today, Carolingian cathedrals and palaces still stand as reminders of this mini-renaissance of the 8th and 9th centuries.

Today, Carolingian cathedrals and palaces still stand as reminders of this mini-renaissance of the 8th and 9th centuries.

The Carolingian renaissance is a reminder that cultural developments are so often implemented hierarchically.

Though it’s tempting to envision a world that’s shaped by organic movements, real civilizational change usually requires a green light from the top.

Though it’s tempting to envision a world that’s shaped by organic movements, real civilizational change usually requires a green light from the top.

If you enjoyed this thread and would like to join the mission of promoting the beauty of western tradition, kindly repost the first post (linked below) and consider following: @thinkingwest

https://twitter.com/thinkingwest/status/1779880372475494434

Carolingian architecture wasn’t as flashy as later movements like Gothic or Baroque, but it had a distinct, almost charming style that set it apart from older Roman construction.

It was the template for a new civilizational look.

It was the template for a new civilizational look.

A last note on Charlemagne: he never actually learned to read or write despite surrounding himself with so many scholars. He simply could not master it in his old age.

He never achieved philosopher-king status, but his people benefited greatly from his educational reforms.

He never achieved philosopher-king status, but his people benefited greatly from his educational reforms.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh