The "science vs religion" dichotomy is false.

In fact, some of the most groundbreaking scientific discoveries were made by Catholic clergy.

Here are the top 5 scientific breakthroughs made by priests…🧵 (thread)

In fact, some of the most groundbreaking scientific discoveries were made by Catholic clergy.

Here are the top 5 scientific breakthroughs made by priests…🧵 (thread)

5) Atomic Theory (Boscovich Model)

Roger Boscovich, a Croatian physicist, astronomer, and mathematician, was a Catholic priest in the Jesuit order. His model of the atom, the “Boscovich Model,” was a forerunner to modern atomic theory.

Roger Boscovich, a Croatian physicist, astronomer, and mathematician, was a Catholic priest in the Jesuit order. His model of the atom, the “Boscovich Model,” was a forerunner to modern atomic theory.

His theory was an attempt to find a middle way between Newton’s theory of gravity and Gottfried Leibniz's metaphysical theory of monad-points (points of original substance).

In addition to physics, Boscovich made significant astronomical observations; in particular the moon.

In addition to physics, Boscovich made significant astronomical observations; in particular the moon.

4) Seismology

One of the pioneers in the field of seismology was Fr. Giuseppe Mercalli in the late 19th and early 20th century.

He’s famous for developing the Mercalli Intensity Scale which measures the intensity of seismic shaking caused by earthquakes.

One of the pioneers in the field of seismology was Fr. Giuseppe Mercalli in the late 19th and early 20th century.

He’s famous for developing the Mercalli Intensity Scale which measures the intensity of seismic shaking caused by earthquakes.

Though the Richter scale superseded his scale for magnitude measurement, the Mercalli scale remains the method for assessing the impact of earthquakes on people and buildings.

Mercalli’s commitment to science and his faith exemplify the harmony between the two realms.

Mercalli’s commitment to science and his faith exemplify the harmony between the two realms.

3) Genetic Theory

Gregor Mendel, “the father of modern genetics,” was a 19th-century Augustinian friar and abbot. He developed Mendelian genetic theory by observing the inherited traits in pea plants, paving the way for our modern understanding of heredity.

Gregor Mendel, “the father of modern genetics,” was a 19th-century Augustinian friar and abbot. He developed Mendelian genetic theory by observing the inherited traits in pea plants, paving the way for our modern understanding of heredity.

Mendel’s discoveries were initially ignored. Notably Charles Darwin had no idea about Mendel’s work. It’s possible had he known, genetics would have developed much earlier.

The significance of his work was only finally realized after his death.

The significance of his work was only finally realized after his death.

2) The Big Bang

The Big Bang theory of the universe’s origin was first posited by Georges Lemaitre, a Belgian astronomer. physicist, and priest. His theory shocked the scientific community when it was first published in 1927, but has since been widely accepted.

The Big Bang theory of the universe’s origin was first posited by Georges Lemaitre, a Belgian astronomer. physicist, and priest. His theory shocked the scientific community when it was first published in 1927, but has since been widely accepted.

Lemaitre’s model upset the millennia-old belief of an eternal cosmos. His theory implied that everything came from an ultra-dense, tiny point, and its expansion birthed time and space.

Contrary to common belief, it was anti-religious sentiment that prevented the Big Bang theory from broad acceptance early on.

Atheist scientists were repulsed by the Big Bang's creationist overtones—it seemed too similar to the creation story in the Book of Genesis.

Atheist scientists were repulsed by the Big Bang's creationist overtones—it seemed too similar to the creation story in the Book of Genesis.

1) Heliocentrism

Nicolaus Copernicus was an early proponent of heliocentrism, the theory that the sun centered the solar system.

It’s possible that Copernicus, a Renaissance-era polymath dubbed the “father of modern astronomy,” was also a Catholic priest.

Nicolaus Copernicus was an early proponent of heliocentrism, the theory that the sun centered the solar system.

It’s possible that Copernicus, a Renaissance-era polymath dubbed the “father of modern astronomy,” was also a Catholic priest.

Copernicus held various positions within the Church, and the Catholic Encyclopedia claims he was ordained since in 1537 he was a candidate for the episcopal seat of Warmia, a seat that required ordination. Some scholars contest whether he was ever actually ordained though.

The idea that science and religion are at odds is a fairly new concept.

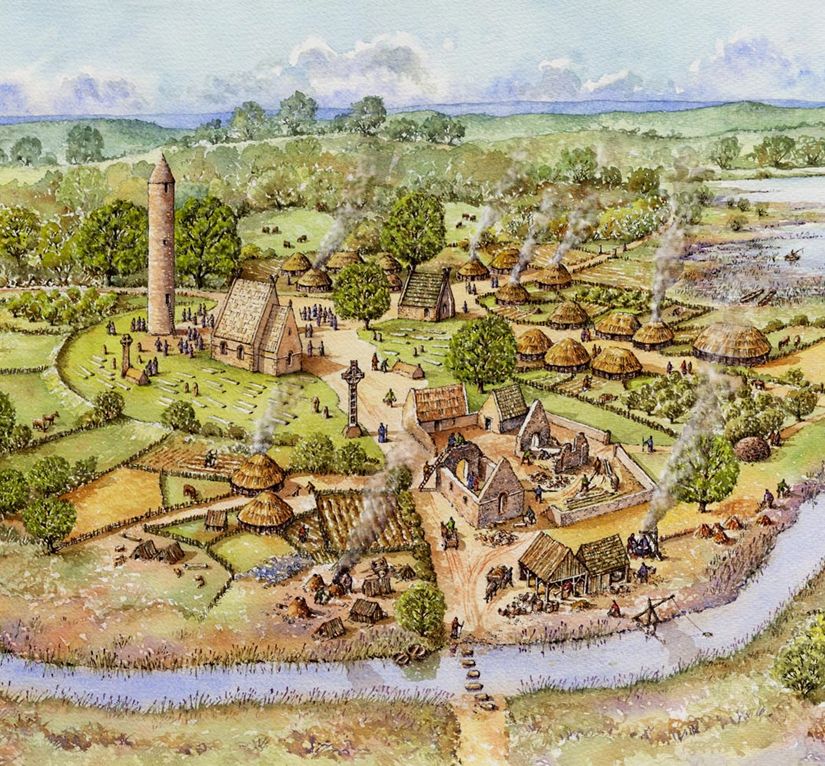

Despite the modern misconception, it’s historically been religious institutions, especially the Catholic Church, who have been the main drivers of scientific advancement in the West.

Despite the modern misconception, it’s historically been religious institutions, especially the Catholic Church, who have been the main drivers of scientific advancement in the West.

If you enjoyed this thread and would like to join the mission of promoting the beauty of western tradition, kindly repost the first post (linked below) and consider following: @thinkingwest

https://twitter.com/thinkingwest/status/1780598348921131074

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh