A democracy can only last 200 years.

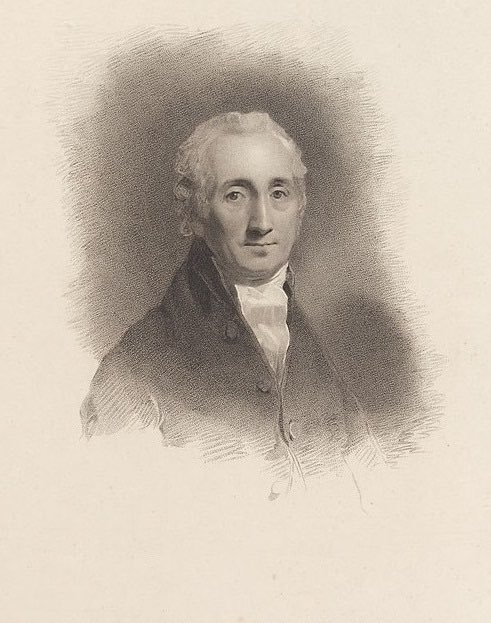

At least, that’s according to 18th-century historian Alexander Tytler.

He claimed democracies always follow a predictable pattern and are doomed to end in servitude…🧵

At least, that’s according to 18th-century historian Alexander Tytler.

He claimed democracies always follow a predictable pattern and are doomed to end in servitude…🧵

Tytler was a Scottish judge, writer, and Professor of Universal History as well as Greek and Roman Antiquities at the University of Edinburgh.

After studying dozens of civilizations, he noticed some intriguing patterns…

After studying dozens of civilizations, he noticed some intriguing patterns…

He believed that democracies naturally evolved from initial virtue to eventual corruption and decline.

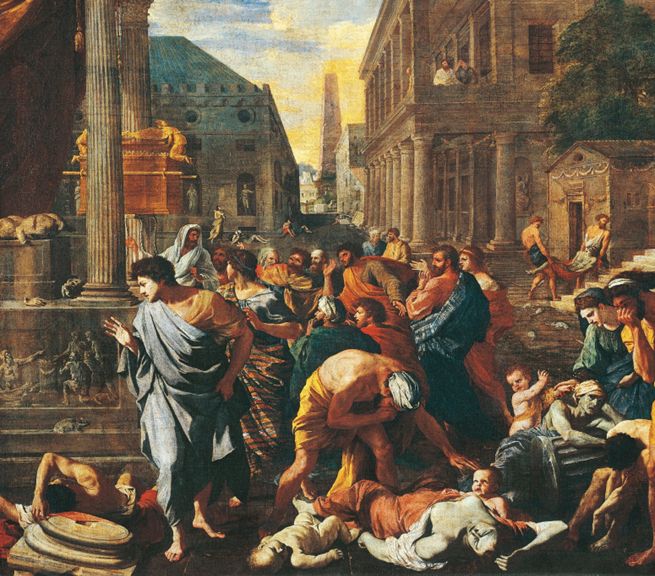

In ancient Greece, for example, he argued that "the patriotic spirit and love of ingenious freedom...became gradually corrupted as the nation advanced in power and splendor."

In ancient Greece, for example, he argued that "the patriotic spirit and love of ingenious freedom...became gradually corrupted as the nation advanced in power and splendor."

A pure democracy was a “chimera” or a “utopian theory”—it never existed, and never could exist because a democracy relied on the virtue of its citizens to function properly.

Basically, without a perfect citizenry a democracy devolves into a worse form of government.

Basically, without a perfect citizenry a democracy devolves into a worse form of government.

Republics also had this problem, and people that disillusioned themselves into envisioning a well-functioning republic were imagining “a republic not of men, but of angels."

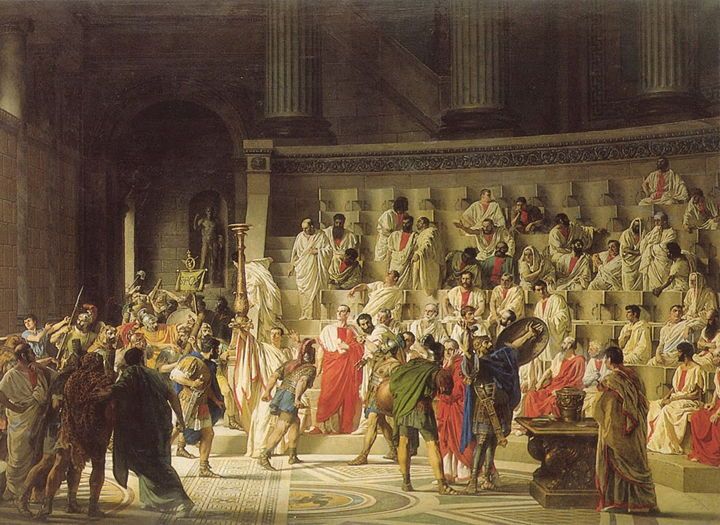

All governments, according to Tytler, actually functioned as either monarchies or oligarchies, regardless of how their leaders were elected.

Once a leader is in place, the people must obey. Democracies and republics are no different.

Once a leader is in place, the people must obey. Democracies and republics are no different.

Voters in democracies were always influenced by the “basest corruption and bribery,” but once leaders were in power, these leaders no longer acted in the interest of the people.

The people had to submit to their rule “as if they were under the rule of a monarch"

The people had to submit to their rule “as if they were under the rule of a monarch"

Tytler also noticed some striking similarities about how democracies end.

Democracies always collapse in the same way—poor monetary policy.

Democracies always collapse in the same way—poor monetary policy.

Tytler writes:

“the majority always votes for the candidates promising the most benefits from the public treasury with the result that a democracy always collapses over loose fiscal policy, always followed by a dictatorship”

“the majority always votes for the candidates promising the most benefits from the public treasury with the result that a democracy always collapses over loose fiscal policy, always followed by a dictatorship”

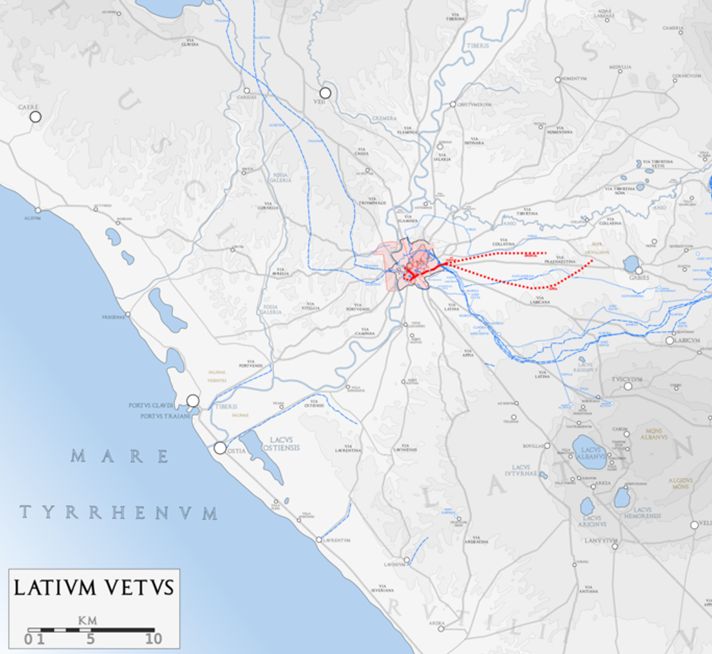

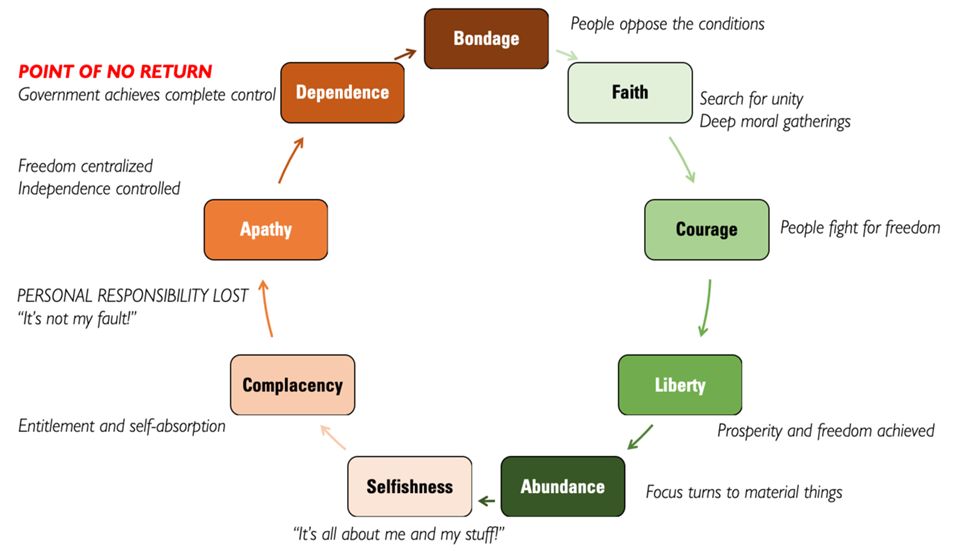

From democracy to dictatorship seems like a big leap, but Tytler laid out the steps that these civilizations always follow—this is the “Tytler Cycle,” and it lasts about 200 years.

Civilizations are broken into a series of stages, with each inevitably leading to the next stage.

Civilizations are broken into a series of stages, with each inevitably leading to the next stage.

The stages are as follows:

“From bondage to spiritual faith; spiritual faith to great courage; courage to liberty; liberty to abundance; abundance to selfishness; selfishness to complacency; complacency to apathy; apathy to dependence; dependence back into bondage”

“From bondage to spiritual faith; spiritual faith to great courage; courage to liberty; liberty to abundance; abundance to selfishness; selfishness to complacency; complacency to apathy; apathy to dependence; dependence back into bondage”

Initially, cultures start out in bondage to superior ones—think America’s colonial past or Israel’s enslavement to Egypt.

But after a courageous revolution, liberty is achieved.

But after a courageous revolution, liberty is achieved.

And through liberty great abundance is attained—a civilization grows wealthy and powerful.

Selfishness and complacency are lurking around the corner, though. This is where the decline starts.

Selfishness and complacency are lurking around the corner, though. This is where the decline starts.

Tytler claims that it is a nation's wealth that weakens its people:

"It is a law of nature to which no experience has ever furnished an exception, that the rising grandeur and opulence of a nation must be balanced by the decline of its heroic virtues"

"It is a law of nature to which no experience has ever furnished an exception, that the rising grandeur and opulence of a nation must be balanced by the decline of its heroic virtues"

The lack of virtue within a nation leads to its atomization. Apathy toward one’s fellow man—and the system as a whole—is commonplace. Then, tyrants are allowed to seize control.

Which ultimately brings a nation full-circle back to the bondage stage.

Which ultimately brings a nation full-circle back to the bondage stage.

Tyter’s Cycle points toward the inevitability of democracies to devolve into tyrannies, an observation other thinkers like Aristotle pointed out too.

But was Tytler’s theory correct? Is democracy doomed to fail after only a couple hundred years?

Where are we now in the cycle?

But was Tytler’s theory correct? Is democracy doomed to fail after only a couple hundred years?

Where are we now in the cycle?

If you enjoyed this thread and would like to join the mission of promoting western tradition, kindly repost the first post (linked below) and consider following: @thinkingwest

https://twitter.com/thinkingwest/status/1781328910161969520

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh