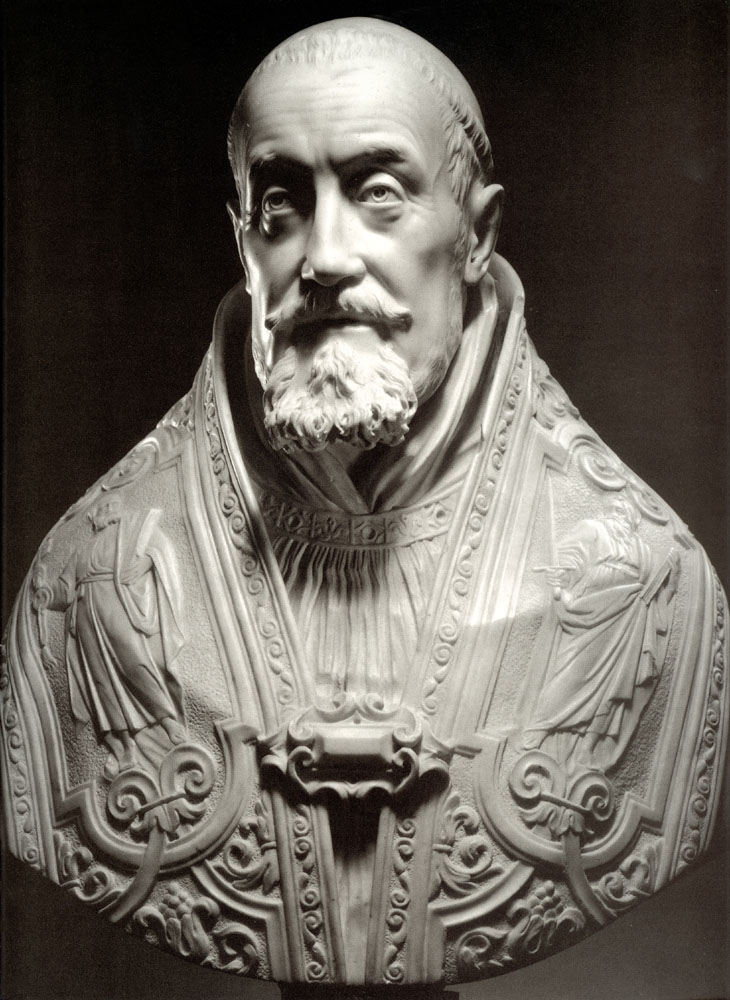

How did a 23-year-old produce sculptures like this?

Not only that — he saved Christian art in the process.

Here's how he did it... (thread) 🧵

Not only that — he saved Christian art in the process.

Here's how he did it... (thread) 🧵

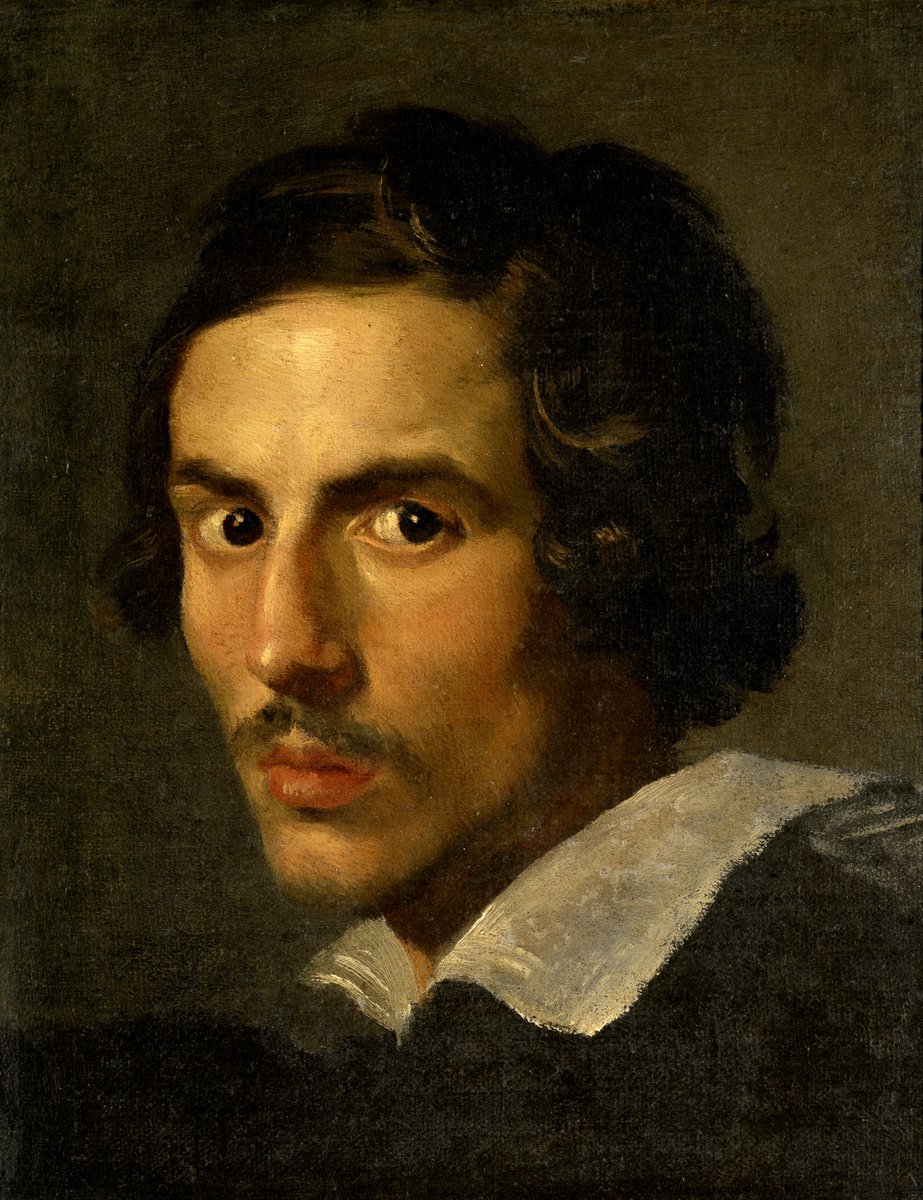

Such skill at that age seems unthinkable. In fact, Gian Lorenzo Bernini was pretty well a master by 15. How?

Well, his father was a sculptor for one thing, and nurtured him early on. At age 11, he was already sculpting marble...

But the young prodigy became driven by something greater: a flourishing Catholic faith.

By 15, he was making devotional art of martyrs, and attempting ambitious feats — like carving flames from solid stone:

By 15, he was making devotional art of martyrs, and attempting ambitious feats — like carving flames from solid stone:

Bernini felt he was doing more than just sculpting. He thought art connected people with God, and sought to create sculptures so realistic and emotive that they could awaken people spiritually.

His devotion took him on the most prolific run of life-size masterpiece creation since Michelangelo. Backed by wealthy patrons, he did all this before turning 26:

Born 3 decades after Michelangelo died, Bernini quickly built a reputation in Rome as the "Michelangelo of his age". It wasn't long before he was producing art for the Pope himself...

By 30 he could carve anything: impossibly supple skin, horses, complex drapery — he even mastered bronze. Some think these achievements surpassed Michelangelo on technical ability...

But he was a profoundly different artist to Michelangelo. He injected new motion into stone — just look how different his interpretation of David was.

He was pioneering a new form of sculpture: Baroque.

He was pioneering a new form of sculpture: Baroque.

He wasn't carving ideal human forms like the Renaissance artists, who turned men into god-like heroes. He was capturing real, mortal humanity — through expressive contortions never seen before.

Renaissance art was about deeper intellectual inquiry. Baroque art was about creating a visual experience so striking that it overwhelms you.

Bernini came at a critical juncture for the Church, because the Protestant Reformation was turning people away from religious art.

Catholicism desperately needed artists to turn them back...

Catholicism desperately needed artists to turn them back...

So, popes put him to work creating art so emotive it could draw them in. The Ecstasy of St. Teresa showed people the ecstatic joy at the moment of a religious transformation:

With these dramatic new art forms, the Catholic Church rebuilt Rome's reputation as the holy city. Bernini's sculptures were central to this lavish vision, both in humble squares and the greatest churches.

He also played a part in Rome's architectural restoration. In later life he turned to architecture, designing the colonnade of St. Peter's Square.

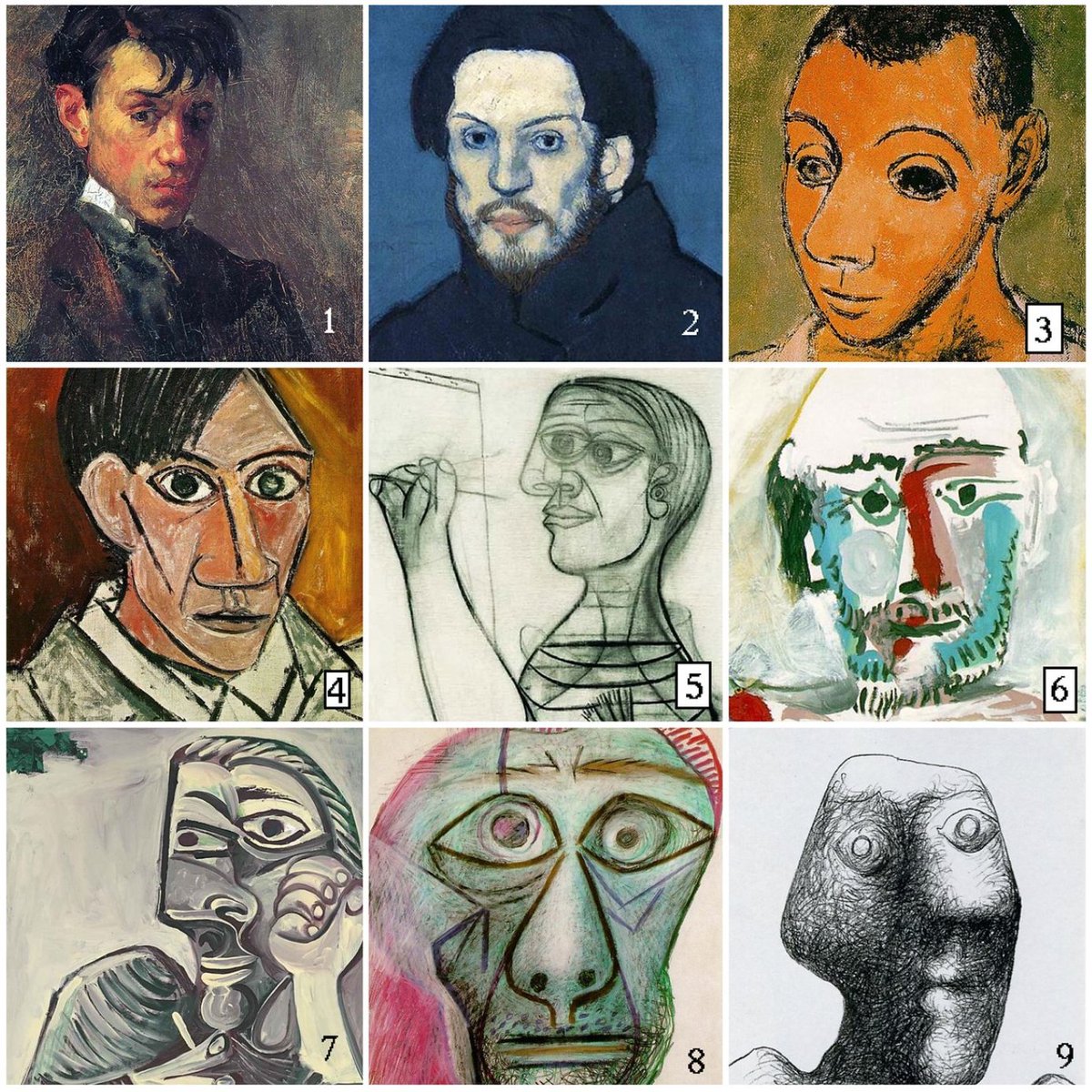

Some say Bernini wasn't a revolutionary (like Michelangelo) because he didn't make radical diversions from what came before. He instead iterated on the Mannerist sculptors that preceded him.

But instead of taking sculpture in new direction, Bernini took it to entirely new heights.

Through sheer pious devotion, he did things with marble that even Michelangelo couldn't...

Through sheer pious devotion, he did things with marble that even Michelangelo couldn't...

If you enjoy these threads, you NEED my newsletter.

34,000 others read it: art, culture, history 👇

culturecritic.beehiiv.com/subscribe

34,000 others read it: art, culture, history 👇

culturecritic.beehiiv.com/subscribe

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh