Why did so many hunter gatherer groups around the world nearly-simultaneously and in an unconnected way develop agriculture?

This has been a kinda problematic question in human prehistory.

It may have been solved... by an economist?

Studying the economics of... Earth's orbit?

This has been a kinda problematic question in human prehistory.

It may have been solved... by an economist?

Studying the economics of... Earth's orbit?

Okay let's back up.

Earth's climate has a lot of moving parts. But a big factor, as every child knows, is that the sun is quite warm. But sometimes, a spot on earth is closer to the sun. And sometimes further. Because our planet is caterwampus, i.e. tilted on its axis.

Earth's climate has a lot of moving parts. But a big factor, as every child knows, is that the sun is quite warm. But sometimes, a spot on earth is closer to the sun. And sometimes further. Because our planet is caterwampus, i.e. tilted on its axis.

However, that tilt isn't stable. It gets, in the formal scientific language, a bit wibbledy wobbledy from time to time. When earth gets a case of the wobbles, the seasons get a little bit funky.

More formally: for idiosyncratic astronomical/physics of planets reasons, there are times when Earth's seasons are more regular and less extreme, and then there are times when Earth's seasons are less regular and more extreme.

Now imagine primordial humans. They hunt. They gather. They have some nice leisure time, chillin in caves, paintin on walls, committing infanticide against 25% of their offspring, etc, etc

The thing is that hunting and gathering is quite seasonally dependent. You have to move around a lot to follow where the edible plants and game are at given points in the season. You do leave behind caches of excess food where you can, but storage is tricky.

As the seasons get funkier, this strategy gets harder and harder. You have to pursue game further, cross more distance, and ultimately you have to store more of your surplus. If you don't increase storage, you starve to death, because periods of zero game/berries get more common.

So as the seasons get funkier, the returns to nomadism decline. This is kind of not what many people intuitively think. "Times get tough, time to hit the road!" Wrong. When times get tough, it's important to expand storage capacity and increase your savings rate.

Groups that respond to increased seasonal irregularity by increasing storage survive more.

But the thing is that nomadism just doesn't allow that much storage. Unattended caches get ruined/stolen/have limited scale, and you can only carry so much stuff with you.

But the thing is that nomadism just doesn't allow that much storage. Unattended caches get ruined/stolen/have limited scale, and you can only carry so much stuff with you.

The need for better storage to enable better consumption smoothing during extended periods of low food availability forces hunter gatherers to adopt sedentary and then agricultural lifestyles.

This doesn't happen in climates where, for whatever reason, increased seasonality didn't present as serious of issues.

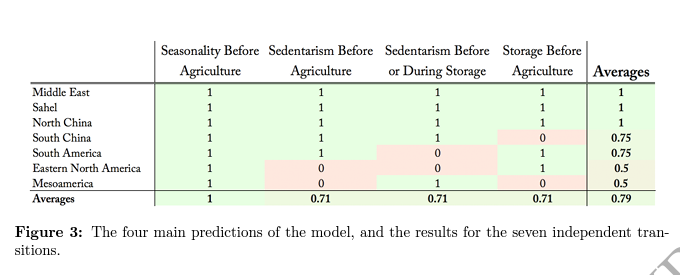

Anyways, a new paper quantifies all of this and shows... it's actually true!

More wobbly seasons == Agriculture gets invented

academic.oup.com/qje/advance-ar…

Anyways, a new paper quantifies all of this and shows... it's actually true!

More wobbly seasons == Agriculture gets invented

academic.oup.com/qje/advance-ar…

So the author, @andreamatranga , shows us stuff like this graph, which is a pretty compelling case that agriculture was invented when seasonality got crunk, and then spread in a seasonality-biased pattern:

Anyways, I remember when @andreamatranga first showed me a draft of this one a few years back, I was immediately struck by how clear and plausible the explanation seemed. Glad to see it reaching the light of day!

We may now know why, after perhaps 200,000 years as hunter gatherers, humans suddenly made a massive shift in subsistence strategy ~10,000 years ago:

Because the Earth went jiggly.

Because the Earth went jiggly.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh