There are a lot of misconceptions about the Inquisition.

Most people today view it as a medieval witch hunt spurred on by dark age superstition—but its initial intentions weren't so misguided…🧵

Most people today view it as a medieval witch hunt spurred on by dark age superstition—but its initial intentions weren't so misguided…🧵

We’ve all heard of “the Inquisition,” but in fact no singular organization existed with this title.

Rather, the term refers to a judicial process by the Catholic Church that sought to combat heresy via trial.

There were multiple inquisitions in response to different heresies.

Rather, the term refers to a judicial process by the Catholic Church that sought to combat heresy via trial.

There were multiple inquisitions in response to different heresies.

The Inquisition we think of today started in the 12th century. It was an attempt to preserve unity of belief in the face of some unorthodox movements.

The Church had fought heresy before, but two particular sects were stirring up a lot of trouble…

The Church had fought heresy before, but two particular sects were stirring up a lot of trouble…

The Cathars and Waldensians were excommunicated groups that held wild beliefs contradicting fundamental Christian teaching.

They briefly held territories in France and Italy, coming to blows with local political and religious leaders.

They briefly held territories in France and Italy, coming to blows with local political and religious leaders.

Both secular leaders and Church authorities had an incentive to restore peace.

In light of the intensity and broad reach of these movements, the Church developed a formal process for rooting them out—the inquisition.

In light of the intensity and broad reach of these movements, the Church developed a formal process for rooting them out—the inquisition.

Initially any local clergyman could act as inquisitor, but by the 1250’s inquisitions became almost exclusively under the purview of the Dominican Order.

They were essentially a “task force” to eliminate heresy.

They were essentially a “task force” to eliminate heresy.

It should be noted that inquisitors had no jurisdiction over Muslims, Jews, or non-believers. They only had authority to investigate the heretical behavior of Christians.

It’s a common misconception that the Inquisition sought to punish non-believers in general.

It’s a common misconception that the Inquisition sought to punish non-believers in general.

So what exactly did inquisitors do?

When someone was accused of heresy, it was the inquisitor’s job to determine if they met the criteria of “major, willful, and unrepentant heresy.”

When someone was accused of heresy, it was the inquisitor’s job to determine if they met the criteria of “major, willful, and unrepentant heresy.”

Inquisitors were called such because they applied the technique of inquisitio—”inquiry”—to potential offenders.

This involved evidence collection, witness testimonies, and a trial.

This involved evidence collection, witness testimonies, and a trial.

In difficult cases, it could also include torture.

Though it was permitted in the 1252 papal bull “Ad extirpanda,” torture was a last resort.

When used, a doctor was required to be present to avoid endangering life.

Though it was permitted in the 1252 papal bull “Ad extirpanda,” torture was a last resort.

When used, a doctor was required to be present to avoid endangering life.

3 non-bloody methods of torture were permitted:

- Strappado: the prisoner was lifted to the ceiling with his arms tied behind his back

- Rack: the prisoner was tied to a frame and stretched

- Water cure: the prisoner was forced to drink large quantities of water in a short time

- Strappado: the prisoner was lifted to the ceiling with his arms tied behind his back

- Rack: the prisoner was tied to a frame and stretched

- Water cure: the prisoner was forced to drink large quantities of water in a short time

And torture had to follow the following rules:

- it cannot endanger the subject's life

- it cannot cause loss of limbs

- it may only be applied once, and only if the subject appeared to be lying

- it was forbidden to torture someone whose guilt had already been determined

- it cannot endanger the subject's life

- it cannot cause loss of limbs

- it may only be applied once, and only if the subject appeared to be lying

- it was forbidden to torture someone whose guilt had already been determined

Despite sometimes excruciating torture methods, sentences for convicted heretics were *usually* light.

If the defendant repented, he or she could be reconciled with the Church. A penance as simple as wearing a cross sewn on one's clothes or going on pilgrimage were common.

If the defendant repented, he or she could be reconciled with the Church. A penance as simple as wearing a cross sewn on one's clothes or going on pilgrimage were common.

For willful, unrepentant heretics, however, canon law required the defendant to be handed over to secular authorities for final sentencing. These secular authorities would determine the penalty based on local law.

Local laws often had steep penalties for religious crimes…

Local laws often had steep penalties for religious crimes…

Banishment or imprisonment for life were common punishments, though sentences were generally commuted after a few years.

Death by burning was the most feared punishment. Though less common, it’s what most people think of today when envisioning the Inquisition.

Death by burning was the most feared punishment. Though less common, it’s what most people think of today when envisioning the Inquisition.

Severe punishments for heresy were not so much to correct the person being punished, but to scare others into submission.

Watching someone burn at the stake would surely do just that.

Watching someone burn at the stake would surely do just that.

A 1578 inquisitional manual writes:

“for punishment does not take place primarily and per se for the correction and good of the person punished, but for the public good in order that others may become terrified and weaned away from the evils they would commit"

“for punishment does not take place primarily and per se for the correction and good of the person punished, but for the public good in order that others may become terrified and weaned away from the evils they would commit"

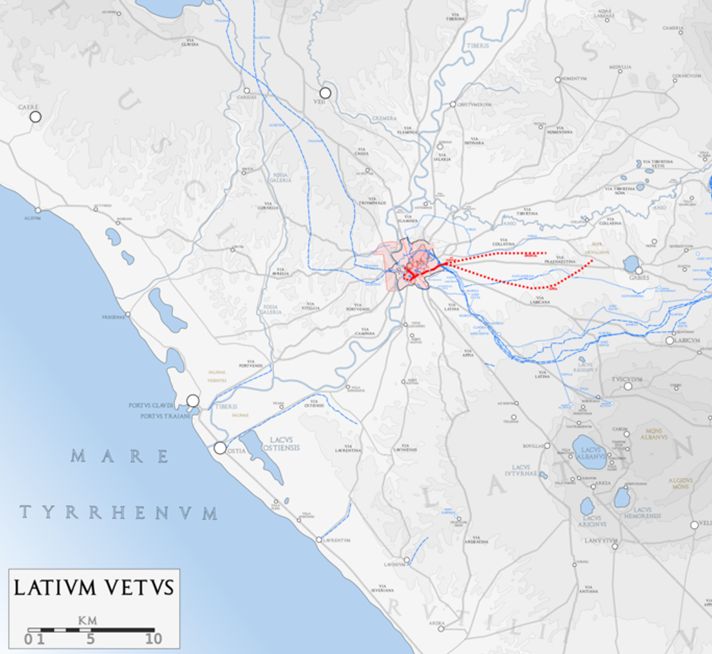

The spirit of inquisition grew far wider than its initial scope in southern France.

Multiple European countries had inquisitions such as Italy, Portugal, Germany, Poland, and of course Spain.

Multiple European countries had inquisitions such as Italy, Portugal, Germany, Poland, and of course Spain.

In some German localities, fear of witches incited frenzied attempts at inquisition.

But it was largely the Catholic Church who fought to dispel notions of witches and witch hunts, condemning them as “pagan superstition.”

But it was largely the Catholic Church who fought to dispel notions of witches and witch hunts, condemning them as “pagan superstition.”

One Dominican priest, Heinrich Kramer, wrote a witch-fighting handbook entitled Malleus Maleficarum — “Hammer Against Witches.”

In 1484, when he asked the pope to grant him inquisitional authority, he was ignored and his local bishop expelled him for making false accusations.

In 1484, when he asked the pope to grant him inquisitional authority, he was ignored and his local bishop expelled him for making false accusations.

Inquisitions reached their heyday around the time of the Protestant Reformation, and by the early 1800’s most countries had abolished them.

The Vatican’s inquisition never officially ended—it morphed into the "Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith,” which aims today to “spread sound Catholic doctrine and defend those points of Christian tradition which seem in danger because of new and unacceptable doctrines."

The Church still grapples with the same difficulties the initial inquisitions sought to address, namely how to preserve Christian unity in the face of so many unorthodox beliefs.

With so many competing denominations in the 21st century, true unity seems like a herculean task.

With so many competing denominations in the 21st century, true unity seems like a herculean task.

If you enjoyed this thread and would like to join the mission of promoting western tradition, kindly repost the first post (linked below) and consider following:

@thinkingwest

@thinkingwest

https://twitter.com/thinkingwest/status/1782418097820901695

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh