A road might seem like a simple thing...

But it was mastery of road construction that made Rome the most connected—and powerful—empire in the ancient world.

Roman roads were engineering marvels in their own right 🧵 (thread)

But it was mastery of road construction that made Rome the most connected—and powerful—empire in the ancient world.

Roman roads were engineering marvels in their own right 🧵 (thread)

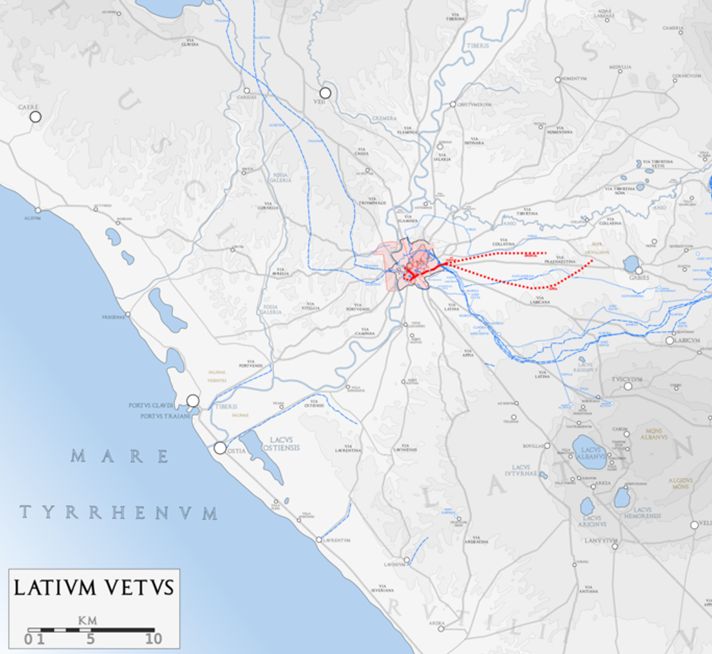

“All roads lead to Rome” is a saying everyone knows. And there’s a reason for it—Rome developed the most incredible network of interconnected highways in the ancient world.

It’s estimated there were over 50,000 miles (~80000 km) of paved roads throughout the empire.

It’s estimated there were over 50,000 miles (~80000 km) of paved roads throughout the empire.

A 4th century surveyor described the extent of the highway system:

“They reach the Wall in Britain; run along the Rhine, the Danube, and the Euphrates; and cover, as with a network, the interior provinces of the Empire.”

“They reach the Wall in Britain; run along the Rhine, the Danube, and the Euphrates; and cover, as with a network, the interior provinces of the Empire.”

Built from the 4th century BC until the decline in the 5th-6th centuries AD, roads were the arteries of the empire, providing efficient means of travel for Rome’s armies, officials, civilians, and trade goods.

Roman roads were constructed so they would require minimal upkeep and provide travelers a smooth journey.

Many of them survive and are still in use today—proof they were engineered with durability in mind.

So how were they built?

Many of them survive and are still in use today—proof they were engineered with durability in mind.

So how were they built?

Rome had 3 types of roads:

-Via terrena: a plain road of leveled earth

-Via glareata: an earthed road with a graveled surface

-Via munita: a paved road with stone and concrete surface

We’ll focus on paved roads for now.

-Via terrena: a plain road of leveled earth

-Via glareata: an earthed road with a graveled surface

-Via munita: a paved road with stone and concrete surface

We’ll focus on paved roads for now.

Paved roads were required by Roman law to be a minimum of 8 feet wide where straight and twice that wide where curved.

Most major roads went beyond this and averaged 12 feet wide, allowing for two passing carts (4 feet each) without interrupting foot traffic.

Most major roads went beyond this and averaged 12 feet wide, allowing for two passing carts (4 feet each) without interrupting foot traffic.

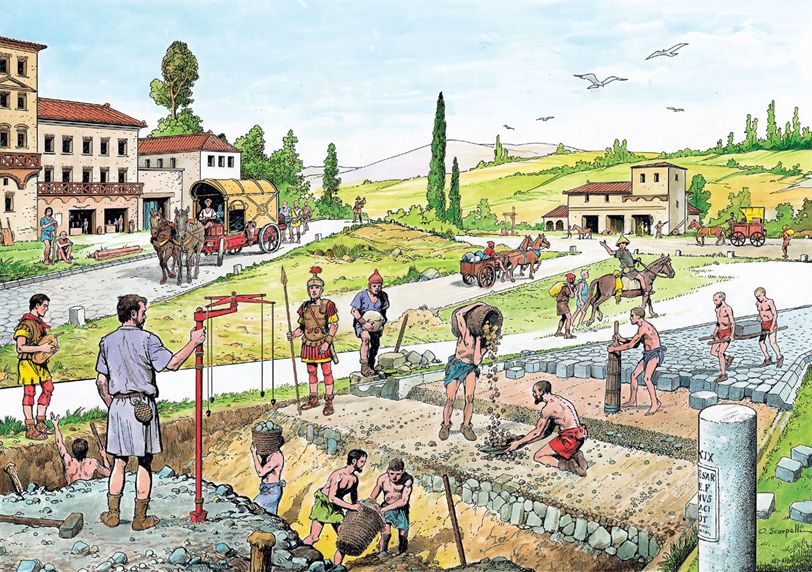

To build a road, a suitable location was first decided by a civil engineer. Agrimensores (land surveyors) worked with the engineer to lay out the route.

Using rods, a straight path was prepared while a groma (a tool that helped obtain right angles) was used to plot a grid.

Using rods, a straight path was prepared while a groma (a tool that helped obtain right angles) was used to plot a grid.

After the general plan was set, workers—and often legionnaires since armies commonly built roads—used plows and spades to dig the road bed down to the bedrock.

This excavation was called the fossa, or “ditch.”

This excavation was called the fossa, or “ditch.”

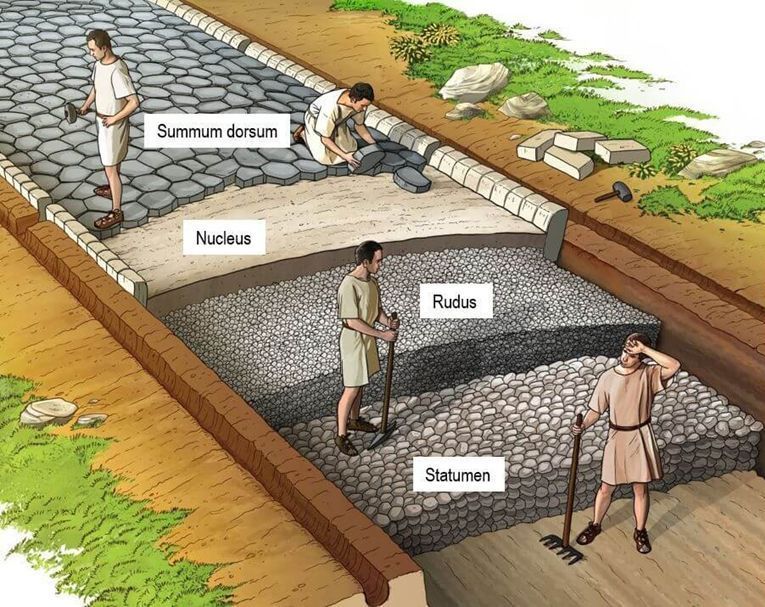

The road was then constructed by filling the ditch in layer by layer. First rubble, gravel, or sand; then, once the ditch was filled within a meter of the surface, it was tamped down to create a flat surface called the pavimentum—“pavement.”

Additional layers were added on top to create a completely smooth surface. A statumen or "foundation" of flat stones set in cement would often support the final layer, which consisted of ployagonal or square paving stones.

This final layer was crowned for drainage.

This final layer was crowned for drainage.

When roads encountered obstacles, Romans preferred to engineer solutions rather than going around them.

Hills or mountains called for digging tunnels or cutting through stone.

Hills or mountains called for digging tunnels or cutting through stone.

Rivers were crossed by constructing bridges, or pontes, which were made of wood or stone.

Wooden bridges were supported by pilings or stone piers, but larger bridges required arches that spanned the width of the river or canyon.

Wooden bridges were supported by pilings or stone piers, but larger bridges required arches that spanned the width of the river or canyon.

Over swampy terrain, causeways were built. These were initially marked out with pilings then built up to about 5 feet above surface-level.

Concrete was an integral part of bridge and causeway construction since it was waterproof.

A mix of volcanic ash, seawater, and lime, roman concrete increased cohesion and strengthened the structure even after it had set.

A mix of volcanic ash, seawater, and lime, roman concrete increased cohesion and strengthened the structure even after it had set.

Another important element of Roman road construction was the mile marker.

Appearing as early as 250 BC in the famed via Appia, mile markers were one thousand paces (~1 mile) apart, marking the distance from the “golden milestone” near the Temple of Saturn in Rome.

Appearing as early as 250 BC in the famed via Appia, mile markers were one thousand paces (~1 mile) apart, marking the distance from the “golden milestone” near the Temple of Saturn in Rome.

So all roads did indeed lead to Rome, but more specifically to this gilded monument.

On the golden milestone were listed distances to all major cities in the empire.

On the golden milestone were listed distances to all major cities in the empire.

Rome's roads were a major reason it expanded so quickly and maintained its dominance for so long.

Well-maintained roads meant troops and resources could traverse the empire quickly—speed of travel was a huge advantage in the ancient world.

Well-maintained roads meant troops and resources could traverse the empire quickly—speed of travel was a huge advantage in the ancient world.

Rome was a nation of builders and conquerors that brought civilization to the far reaches of the known world.

Rome's roads facilitated this civilizing spirit.

Rome's roads facilitated this civilizing spirit.

If you enjoyed this thread and would like to join the mission of promoting western tradition, kindly repost the first post (linked below) and consider following: @thinkingwest

https://twitter.com/thinkingwest/status/1783867135896195073

A pretty cool video explaining Roman roads

Turn on closed captions unless you're fluent in Latin!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh