🧵 Antisocial criminals are the “root cause” of violent crime—not poverty, educational gaps, or a lack of job opportunities.

https://twitter.com/davidjtrone/status/1787135190151684415

Notice the vagueness throughout the OP. Those who advance this claim (against the weight of the evidence) never bother to explain the mechanics of how poverty, unemployment or educational inequities cause a man to stab a teenage girl to death because she rejected his advances.

Here you have a literal millionaire gangster who live-streamed himself shooting an unarmed man at point blank range over nothing. Why didn’t his immense wealth stop this shooting from happening?

chicago.suntimes.com/tj-jimenez/202…

chicago.suntimes.com/tj-jimenez/202…

Consider also this case of another millionaire who killed a guy over a $1,200 drug debt. Why? Not because he was poor. It was, according to a key witness in the case, “the principle.” pennlive.com/crime/2023/05/…

And how does this claim (“poverty, etc. causes crime”) explain the many crimes committed the Bernie Madoffs, Jordan Belforts, Eliot Spitzers, etc.? They don’t say.

The reality is that the relationship between crime—esp. violent crime—doesn’t run in the direction these folks claim. Are many offenders poor, undereducated, and underemployed? Yes. But they never consider that these things are outcomes associated w/ antisocial dispositions.

Then there’s the lack of relationship between crime measures and socioeconomic indicators at a macro level. E.g., in 1990, NYC had 2,262 homicides. By 2017, that number was down to 292. Did NYC solve poverty? No. NYC’s poverty rate in 1989: 18.8%. In 2016: 19.5%.

Did violent crime rise during the Great Recession? Nope. Between 2006–2009, NYC’s unemployment rate for working age black men jumped from 9% to 17.9%. NYC homicides fell from 596–471 over that period.

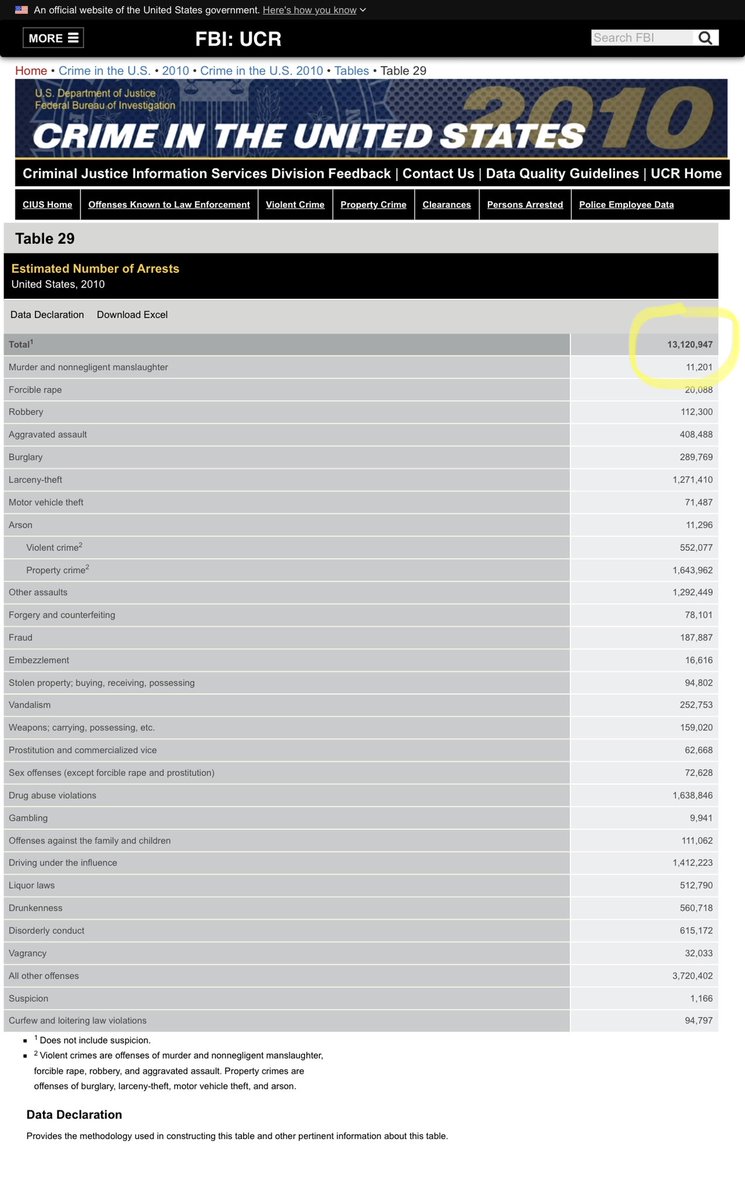

Nationally, the homicide rate dipped 15% between 2007-2010, despite the unemployment rate doubling. And between 1980–2016, income inequality rose by 20%; but the violent crime rate declined from 593.5 per 100k to 386.3 per 100k.

NOT what you’d expect if poverty, etc. ➡️ crime.

NOT what you’d expect if poverty, etc. ➡️ crime.

Then there’s the “Crime/Adversity Mismatch” problem articulated by Barry Latzer, which shows that there exist massive disparities in group offending rates between groups with similar levels of socioeconomic status.

Then there’s the within-group changes in both socioeconomic status and criminal perpetration over time, which are also incongruent with the theory posited in the OP. See, e.g. screenshotted excerpt from my book 👇🏽

The only reliable short-to-intermediate-term solution to crime, as Barry Latzer and I argue in the piece below, is NOT attempting to solve society’s most intractable problems (poverty, inequality, etc.), but rather to responsibly enforce the law: city-journal.org/article/the-en…

As for the half-hearted “systemic racism” claim advanced by Mr. Trone, understand that it is a claim with many holes. The biggest of them is that the claim’s singular focus on disparities in *enforcement,* as if enforcement measures are the system’s only outputs. They’re not.

What Trone and others don’t realize is that there are very stark disparities in violent victimization (see below). These disparities tell us not only who suffers the brunt of the violence problem, but also who stands to gain the most from violent crime reductions.

The undeniable reality is that policing reduces crime (see trove of evidence in thread below). So does incarceration.

https://twitter.com/rafa_mangual/status/1773164080053780658

Both policing and incarceration combined to produce a big chunk of the 1990s homicide decline. And how were the benefits of that decline distributed demographically? 🤔

So here’s the $6M question: Why would a “racist” system so disproportionately *benefit* the group Trone says the system discriminates against?

//end rant//

//end rant//

Relationship between crime *and poverty, etc.* (pardon the typo)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh