Let’s talk about guilds.

Starting as loose agreements between merchants, they developed into powerful political organizations that shaped medieval society and paved the way for modern Europe…🧵

Starting as loose agreements between merchants, they developed into powerful political organizations that shaped medieval society and paved the way for modern Europe…🧵

First off, what were guilds?

Popular in medieval Europe, guilds were groups of craftsmen or traders who got together to protect mutual interests. This could mean quality control, reducing competition, or helping each other financially.

Sort of an “alliance” of business folk.

Popular in medieval Europe, guilds were groups of craftsmen or traders who got together to protect mutual interests. This could mean quality control, reducing competition, or helping each other financially.

Sort of an “alliance” of business folk.

There were two main types of guilds: merchant guilds and craft guilds.

Merchant guilds comprised all or most of the merchants in a particular town or city. These could be local traders or wholesale/retail sellers dealing in various types of goods.

Merchant guilds comprised all or most of the merchants in a particular town or city. These could be local traders or wholesale/retail sellers dealing in various types of goods.

Craft guilds, on the other hand, centered around a certain industry.

For instance there were guilds of weavers, masons, architects, painters, metalsmiths, bakers, butchers, leatherworkers, etc.

Pretty much every industry had a guild of some sort.

For instance there were guilds of weavers, masons, architects, painters, metalsmiths, bakers, butchers, leatherworkers, etc.

Pretty much every industry had a guild of some sort.

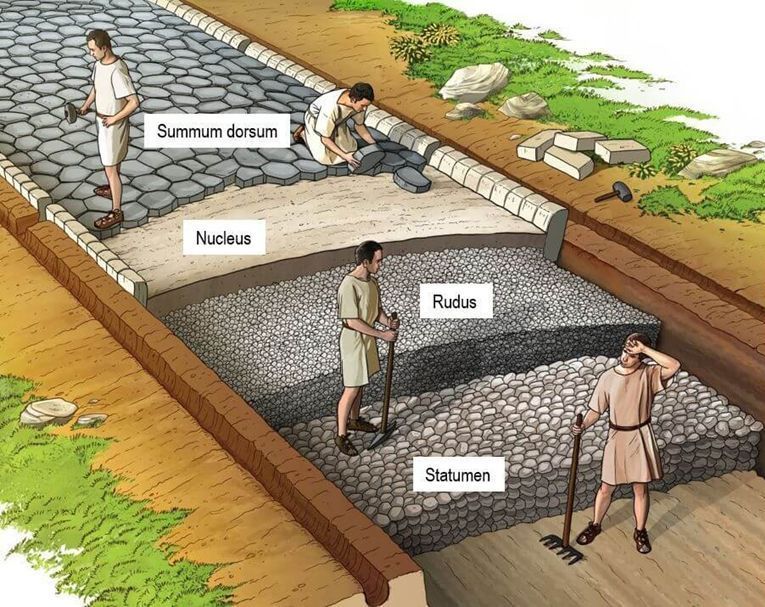

The history of guilds goes back to ancient Rome, where they were called ‘collegia.’ These were mostly hereditary organizations sanctioned by the government.

With the fall of the Western Roman Empire, though, guilds disappeared from European society for several centuries.

With the fall of the Western Roman Empire, though, guilds disappeared from European society for several centuries.

Traders during the early middle ages were mostly wandering peddlers who traveled from town to town, sometimes banding together to protect themselves from bandits.

But as larger cities developed in the 10th and 11th centuries, more complex organization was possible.

But as larger cities developed in the 10th and 11th centuries, more complex organization was possible.

Merchants began delegating certain tasks like transportation of goods to others while they based themselves in cities as their hubs.

Eventually, town governments recognized the associations, and guilds became intimately involved in regulating and protecting members’ commerce.

Eventually, town governments recognized the associations, and guilds became intimately involved in regulating and protecting members’ commerce.

By the 12th century, guilds were everywhere.

In Britain, well over 100 guilds represented traders and craftsmen from industries like weaving and metalwork. Florence boasted 21 guilds while its clothmaking guild represented some 30,000 workers. Paris had 120 guilds.

In Britain, well over 100 guilds represented traders and craftsmen from industries like weaving and metalwork. Florence boasted 21 guilds while its clothmaking guild represented some 30,000 workers. Paris had 120 guilds.

Their sheer numbers allowed them to have immense political influence.

In the 13th century, guilds were made up of wealthy and influential citizens. Town councils were dominated by guild members, and legislation usually favored guild activity.

In the 13th century, guilds were made up of wealthy and influential citizens. Town councils were dominated by guild members, and legislation usually favored guild activity.

In Paris, guilds grew so powerful that they monopolized trade on the River Seine and had authority over petty crimes and the city's grain quotas.

In many cities it was nearly impossible to have a political career without being a guild member.

In many cities it was nearly impossible to have a political career without being a guild member.

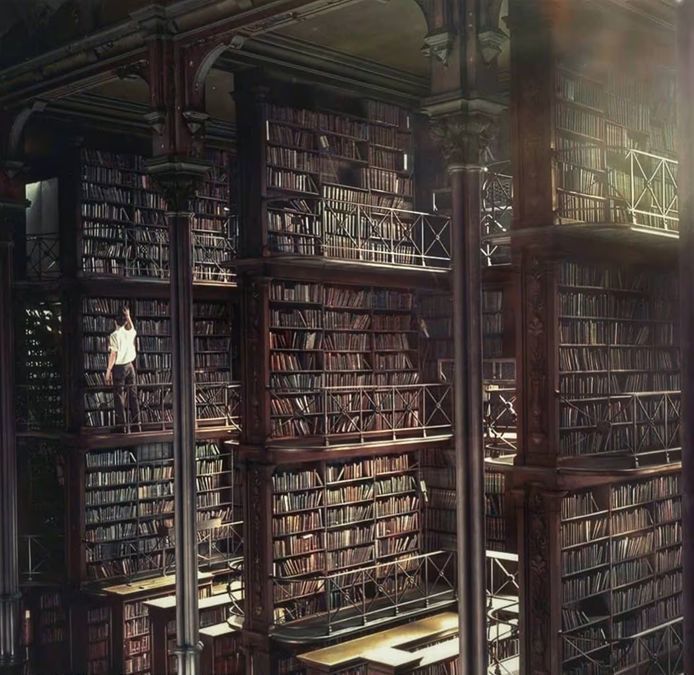

Guilds achieved great influence through the power of collective bargaining, but their organizational structure also played a role.

They were organized into a strict hierarchy that’s still used in many industries today.

They were organized into a strict hierarchy that’s still used in many industries today.

To enter a guild, established merchants or craftsmen had to “buy in”—in fact the name ‘guild’ comes from the Saxon word ‘gilden,’ meaning 'to pay.'

However, young unskilled workers could enter a guild by becoming apprentices in exchange for their labor.

However, young unskilled workers could enter a guild by becoming apprentices in exchange for their labor.

Apprentices would work unpaid for a master, though they were often provided with food, shelter, and an education in their craft. After roughly 5-9 years, they would be competent enough to become journeymen.

Journeymen had the right to be paid for their labor. They still worked for a master, but once a journeyman provided proof of technical expertise in the form of a ‘masterpiece,’ he would join their ranks and start his own establishment.

Guild masters were the inner circle of the guild. They managed the other members and ensured high production standards for their industry.

Sometimes they even performed random checks to make sure their members’ products were up to snuff.

Sometimes they even performed random checks to make sure their members’ products were up to snuff.

One Parisian baker recorded the process:

“If the master determines that the bread is not adequate, he can confiscate all the rest of it, even that which is in the oven. And if there are several types of bread in a window, the master will have each one assessed.”

“If the master determines that the bread is not adequate, he can confiscate all the rest of it, even that which is in the oven. And if there are several types of bread in a window, the master will have each one assessed.”

Besides ensuring quality products and assisting their members, guilds contributed to their local communities.

They donated to the poor and helped build churches, and their guildhalls often served as centers of organization for entire towns.

They donated to the poor and helped build churches, and their guildhalls often served as centers of organization for entire towns.

The Florentine church Orsanmichele was constructed by the city’s guilds in the late 14th century. Each guild filled one of its 14 exterior niches with a statue of their patron saint.

They commissioned the best artists of the day: Ghiberti and Donatelllo to name a couple.

They commissioned the best artists of the day: Ghiberti and Donatelllo to name a couple.

Despite wielding great power during the high middle ages and early renaissance, guilds began to decline in the 16th-17th centuries as merchants began to form companies.

And as technological innovation quickened, craft guilds lost their hold over industries.

And as technological innovation quickened, craft guilds lost their hold over industries.

The most lasting effect of guilds was their influence on the economic organization of Europe.

They bolstered the base of craftsmen, merchants, artisans, and bankers allowing a transition from feudalism to rudimentary capitalism.

They bolstered the base of craftsmen, merchants, artisans, and bankers allowing a transition from feudalism to rudimentary capitalism.

Guilds caused a power shift by creating a distinct merchant class in societies that previously only had three basic classes: clergy, lords, and peasants. Merchants became a new “middle class.”

If you enjoyed this thread and would like to join the mission of promoting western tradition, kindly repost the first post (linked below) and consider following: @thinkingwest

https://twitter.com/thinkingwest/status/1788215286056788058

Guilds could identify each other based on coats-of-arms. Their crests would usually contain imagery related to their industries.

Can you identify which type of guilds these are based on their crests?

Can you identify which type of guilds these are based on their crests?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh