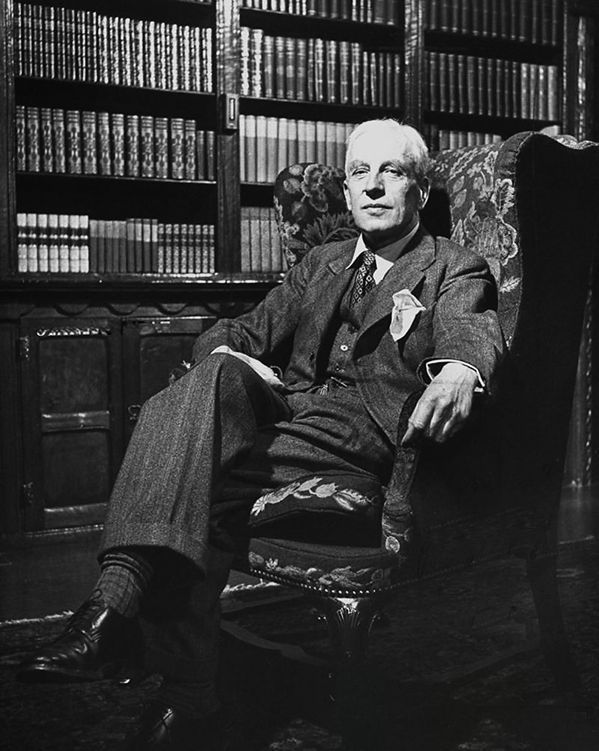

“Civilizations die from suicide, not by murder,” according to 20th-century historian Arnold Toynbee.

He claimed every great culture collapses internally due to a divergence in values between the ruling class and the common people…🧵

He claimed every great culture collapses internally due to a divergence in values between the ruling class and the common people…🧵

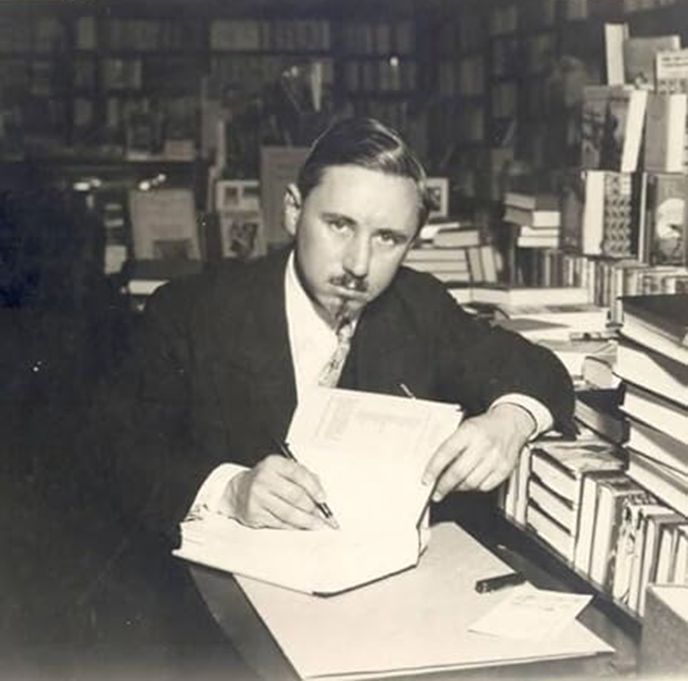

Toynbee was an English historian and expert on international affairs who published the 12 volume work “A Study of History,” which traced the life cycle of about two dozen world civilizations.

Through his work he developed a model of how cultures develop and finally die…

Through his work he developed a model of how cultures develop and finally die…

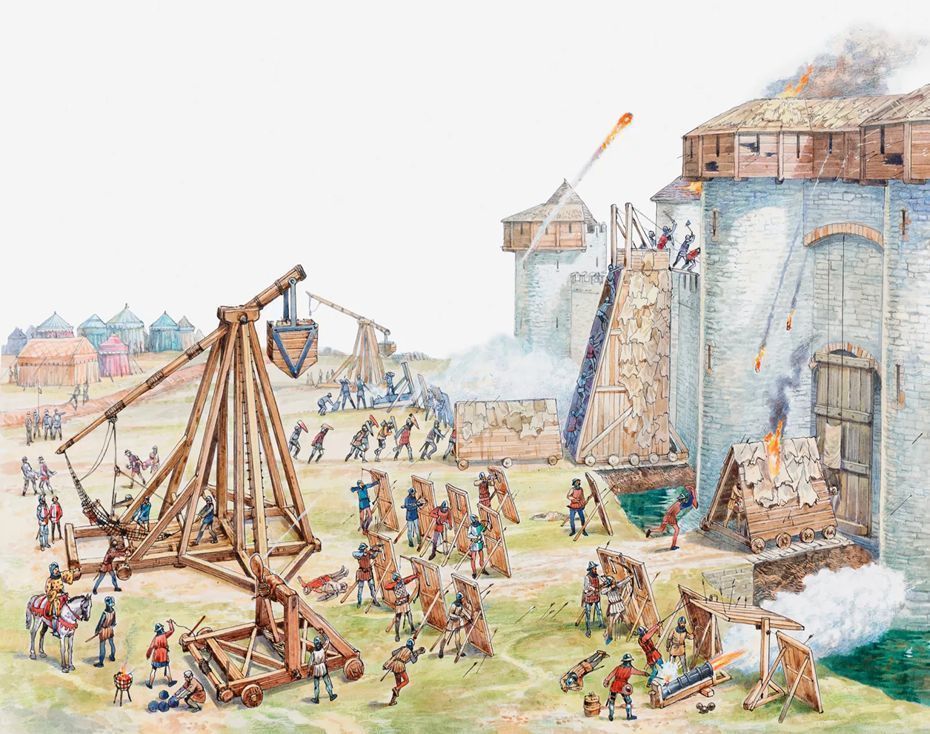

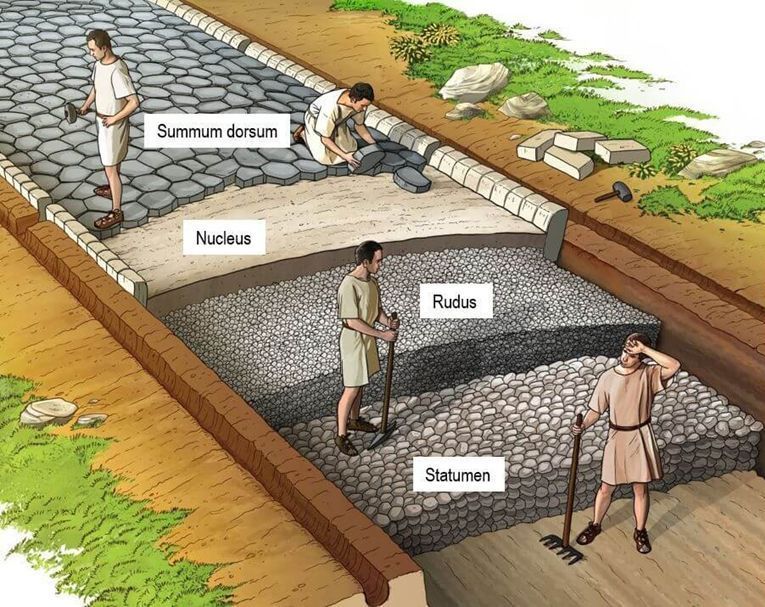

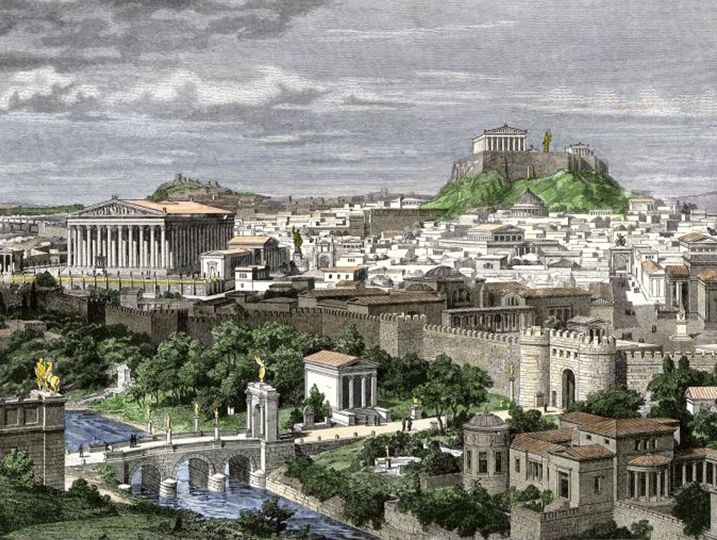

Toynbee argued that civilizations are born primitive societies as a response to unique challenges—pressures from other cultures, difficult terrain or “hard country,” or warfare.

Toynbee writes:

“Civilizations, I believe, come to birth and proceed to grow by successfully responding to successive challenges.”

But each challenge must be a “golden mean” between excessive difficulty, which will crush a culture, and ease, which will allow it to stagnate.

“Civilizations, I believe, come to birth and proceed to grow by successfully responding to successive challenges.”

But each challenge must be a “golden mean” between excessive difficulty, which will crush a culture, and ease, which will allow it to stagnate.

He believed civilizations continued to grow so long as they meet and solve new challenges, one after the other, in a cycle he calls “Challenge and Response.”

Thus, each civilization develops differently because each confronts and overcomes different challenges.

Thus, each civilization develops differently because each confronts and overcomes different challenges.

But societies do not respond to challenges as a whole; rather, it's a unique class of elites within a society that are the problem solvers.

He calls them the "creative minorities" who find solutions to challenges, and inspire—rather than force—others to follow their lead.

He calls them the "creative minorities" who find solutions to challenges, and inspire—rather than force—others to follow their lead.

The masses follow the solutions of the creative minorities by 'mimesis' or imitation, solutions they would have otherwise been incapable of discovering on their own.

This synchronicity between the creative minorities and the masses brings civilization to its height.

This synchronicity between the creative minorities and the masses brings civilization to its height.

Toynbee did not attribute the breakdown of civilizations to environmental forces or external attacks by other civilizations. Rather, it is the decline of the creative minority that leads to a culture’s downfall.

Through moral decay or material prosperity, the creative minority degenerates. They are no longer the great men who solve society’s problems but are simply a ruling class intent on preserving their power.

They become what Toynbee calls the “dominant minority.”

They become what Toynbee calls the “dominant minority.”

Toynbee points to a kind of self worship that takes hold of the dominant minority.

They become prideful about their positions of authority yet are wholly inadequate to deal with the culture’s new challenges.

They become prideful about their positions of authority yet are wholly inadequate to deal with the culture’s new challenges.

Ultimately the dominant minority, incapable of solving their culture’s actual problems, form a “universal state” in a gambit to shore up their power, but it stifles creativity and subjugates the proletariat (common people). Toynbee used the Roman Empire as a classic example.

Toynbee writes:

"First the Dominant Minority attempts to hold by force—against all right and reason—a position of inherited privilege which it has ceased to merit; and then the Proletariat repays injustice with resentment, fear with hate, and violence with violence.”

"First the Dominant Minority attempts to hold by force—against all right and reason—a position of inherited privilege which it has ceased to merit; and then the Proletariat repays injustice with resentment, fear with hate, and violence with violence.”

As society deteriorates, four sentiments exist within the proletariat:

Archaism - idealization of the past

Futurism - idealization of the future

Detachment - removal of oneself from a decaying world

Transcendence - confronting the decaying world with a new worldview

Archaism - idealization of the past

Futurism - idealization of the future

Detachment - removal of oneself from a decaying world

Transcendence - confronting the decaying world with a new worldview

From the disunity between the dominant minority and the proletariat, and between the different proletariat dispositions, a unified culture is impossible, and the civilization eventually ends.

Toynbee sums up the three aspects of failing cultures:

“...a failure of creative power in the minority, an answering withdrawal of mimesis (imitation) on the part of the majority, and a consequent loss of social unity in the society as a whole.”

“...a failure of creative power in the minority, an answering withdrawal of mimesis (imitation) on the part of the majority, and a consequent loss of social unity in the society as a whole.”

It’s interesting to observe Toynbee’s formulation in light of the West’s current struggles.

What do you think—was Toynbee observing universal patterns of civilizational development that might shed light on our culture today?

What do you think—was Toynbee observing universal patterns of civilizational development that might shed light on our culture today?

If you enjoyed this thread and would like to join the mission of promoting western tradition, kindly repost the first post (linked below) and consider following: @thinkingwest

https://twitter.com/thinkingwest/status/1788938804914442303

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh