In 1942, the U.S. government forcibly removed more than 110,000 ethnically Japanese people from their homes and sent them to internment camps in remote parts of the country.

People are resilient, but losing everything is hard.

How did victims' lives turn out?🧵

People are resilient, but losing everything is hard.

How did victims' lives turn out?🧵

First, we need background.

Japanese citizens began arriving to the U.S. in the latter part of the 19th century.

The scale of migration was substantial. By 1942, 40% of Hawaii was Japanese (Hawaii wasn't a state until 1959).

Japanese citizens began arriving to the U.S. in the latter part of the 19th century.

The scale of migration was substantial. By 1942, 40% of Hawaii was Japanese (Hawaii wasn't a state until 1959).

This influx of immigrants quickly became a political problem.

1886-1911, more than 400,000 Japanese set out to American lands. Citizens called for an end, resulting in the Gentleman's Agreement of 1907:

The U.S. wouldn't harass its Japanese and Japan would restrict emigration.

1886-1911, more than 400,000 Japanese set out to American lands. Citizens called for an end, resulting in the Gentleman's Agreement of 1907:

The U.S. wouldn't harass its Japanese and Japan would restrict emigration.

Immigration from Japan was cut down to virtually nothing from 1924 to 1952, creating a "missing generation" of people and distinguishing the first-generation "Issei" from their American-born "Nisei" children.

By 1940, Hawaii had 160,000 or so Japanese residents and the U.S. proper (recall, Hawaii was not a state) had an additional roughly 120,000.

As you can see, the largest portion of them were in California, in both Census and interment camp-derived figures.

As you can see, the largest portion of them were in California, in both Census and interment camp-derived figures.

On December 7th, 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, resulting in the deaths of 2,008 sailors, 109 Marines, 208 soldiers, and a further 68 civilians and ten others, along with the destruction of almost 200 aircraft, four battleships, and more.

With Japan's declaration of war, Issei transformed into enemy aliens on U.S. soil.

The first governmental response was for the FBI to start rounding up community leaders, resulting in the detention of 222 Italian, 1,221 German, and 1,460 Issei men that month.

The first governmental response was for the FBI to start rounding up community leaders, resulting in the detention of 222 Italian, 1,221 German, and 1,460 Issei men that month.

The Ni'ihau Incident that happened after the bombing of Pearl Harbor also started to cement into American's minds the problem of enemy aliens.

Shigenori Nishikaichi crash landed his Zero after the attack and two Japanese island residents agreed to help him.

Shigenori Nishikaichi crash landed his Zero after the attack and two Japanese island residents agreed to help him.

The Haradas (an Issei couple) and Ishimatsu Shintani helped Shigenori get his equipment + papers + torch his plane while kidnapping three native Hawaiians

The Hawaiians fought back. They killed Nishikaichi, Yoshio Harada killed himself, and Shintani and Yoshio's wife were caught

The Hawaiians fought back. They killed Nishikaichi, Yoshio Harada killed himself, and Shintani and Yoshio's wife were caught

Around that time, FDR and Attorney General Biddle made statements calling for Americans to respect the rights of minorities including enemy aliens.

But shortly after that on February 19, FDR signed Executive Order 9066, allowing the military to set up exclusion zones.

But shortly after that on February 19, FDR signed Executive Order 9066, allowing the military to set up exclusion zones.

The EO didn't specify anything for Japanese Americans, but it didn't have to, because Japan was busy frightening American civilians and military personnel.

On February 23rd, Japan bombed an oil field near Santa Barbara.

On February 23rd, Japan bombed an oil field near Santa Barbara.

From November 1944 to April 1945, the Japanese had been launching Fu-Go balloon bombs that ended up dropping incendiary munitions in California and fourteen other states.

The Japanese also attacked a baker's dozen U.S. ships off the California coast.

The Japanese also attacked a baker's dozen U.S. ships off the California coast.

Americans were so afraid of a Japanese invasion that they inflicted damage on themselves in the "Battle of Los Angeles."

The fear was rightful: The Japanese had subs 20 miles from California on December 24, 1941 and California only had sixteen modern airplanes protecting it!

The fear was rightful: The Japanese had subs 20 miles from California on December 24, 1941 and California only had sixteen modern airplanes protecting it!

Leveraging the powers granted by the EO, the military split the West Coast into two military areas and began distributing signs encouraging Japanese people to go East.

The voluntary migration scheme failed and the War Relocation Authority was set up to administer ten camps scattered across the U.S., for 110,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast

These relocated people had to get out quickly, selling possessions at "fire sale" prices

These relocated people had to get out quickly, selling possessions at "fire sale" prices

It's from this background that the analysis begins:

Arellano-Bover used Census, Japanese-American Research Project, and War Relocation Authority data to identify interned Japanese Americans so data on their socioeconomic outcomes could be put to use.

Arellano-Bover used Census, Japanese-American Research Project, and War Relocation Authority data to identify interned Japanese Americans so data on their socioeconomic outcomes could be put to use.

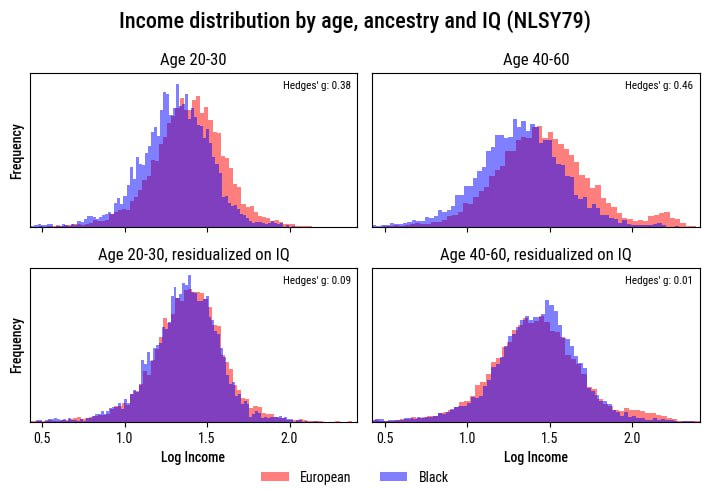

If we look at home ownership after the war, we see that the interned Japanese were definitely negatively impacted:

In the period 1946-52, they had significantly lower homeownership rates than Japanese Americans who weren't interned.

But look at 1953 to the '60s. Recovery?

In the period 1946-52, they had significantly lower homeownership rates than Japanese Americans who weren't interned.

But look at 1953 to the '60s. Recovery?

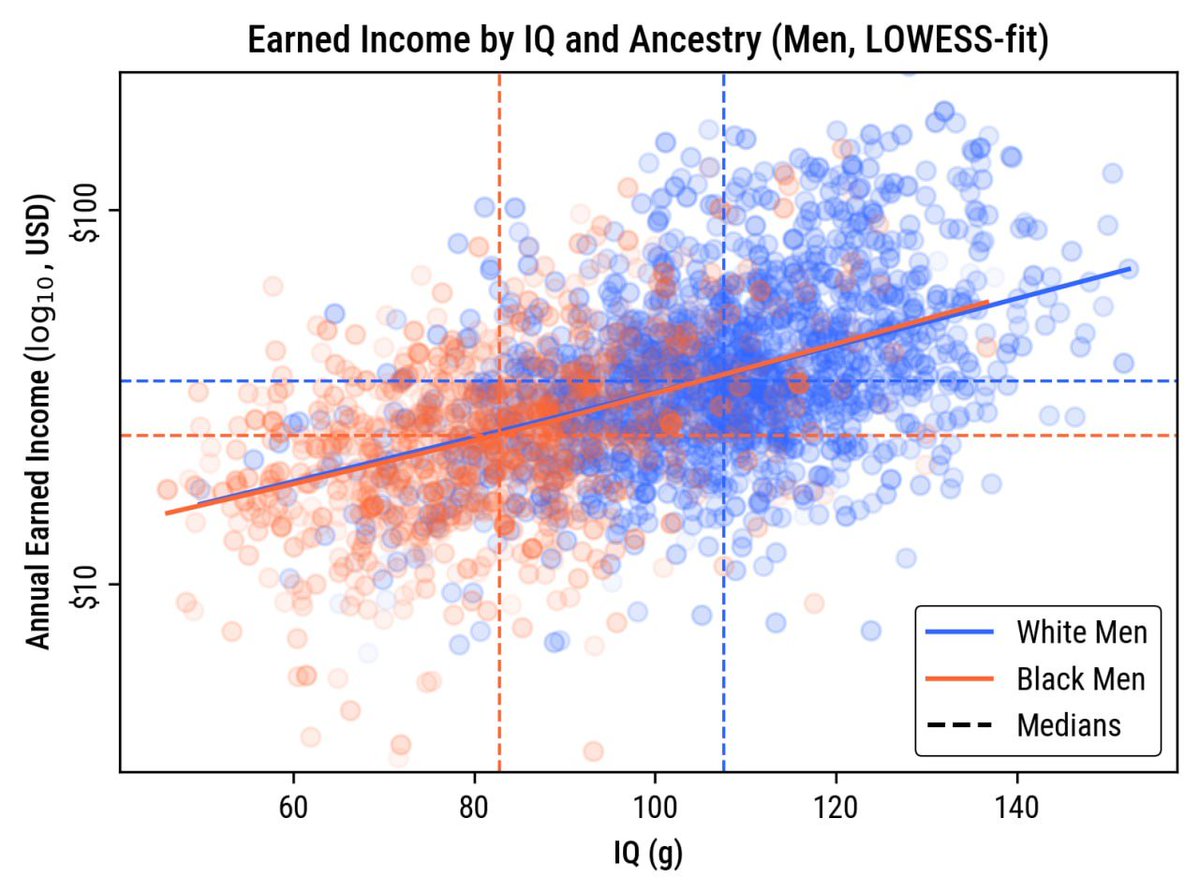

Homeownership is about an asset. If we look at income data, we actually see that the Japanese who would go on to be interned had lower incomes than the non-interned Japanese in 1940, and equal incomes by 1950-60.

So the internment... raised incomes?

So the internment... raised incomes?

The answer to this seems to be "Yes."

Not only did the Japanese who were interned recover, they caught up despite starting further behind the Japanese who weren't interned.

This result is actually very robust!

Not only did the Japanese who were interned recover, they caught up despite starting further behind the Japanese who weren't interned.

This result is actually very robust!

So we have to ask Why?

Let's check attitudes towards work.

Bupkes. The interned and non-interned Japanese don't differ in work attitudes, so they couldn't get ahead that way.

Let's check attitudes towards work.

Bupkes. The interned and non-interned Japanese don't differ in work attitudes, so they couldn't get ahead that way.

What about attachment to Japan and Japanese culture?

Sansei (third-generation Japanese) were just as likely to have Japanese-speaking grandparents and citizenship/Americanness-wise, if anything, the interned were a bit less American.

This probably isn't it either.

Sansei (third-generation Japanese) were just as likely to have Japanese-speaking grandparents and citizenship/Americanness-wise, if anything, the interned were a bit less American.

This probably isn't it either.

Here's the meat:

In 1940, Japanese on the West Coast were disproportionately likely to be farmers and unskilled laborers, whereas the Japanese who migrated East and were thus less likely to be interned worked more often in skilled occupations.

In 1940, Japanese on the West Coast were disproportionately likely to be farmers and unskilled laborers, whereas the Japanese who migrated East and were thus less likely to be interned worked more often in skilled occupations.

This migration-related occupational stratification must not have been very selective by ability, because the interned/non-interned converged.

They also converged, in part, because the interned used the experience to move and change jobs.

They also converged, in part, because the interned used the experience to move and change jobs.

The camps had more socioeconomic diversity than the places internees came from, so they were exposed to a diversity of opportunities and their family ties binding them to certain occupations were broken.

There were frictions the camps help them to overcome!

There were frictions the camps help them to overcome!

It was common to hear stories about internees entering poor and vowing to make it big when they got out, like this pictured one.

And that's what they did: interned Japanese Americans overcame the experience and wound up, miraculously, better off for it.

And that's what they did: interned Japanese Americans overcame the experience and wound up, miraculously, better off for it.

If you're interested in learning more about this amazing example of human resilience in the face of discriminatory adversity, go read the paper, here: cambridge.org/core/journals/…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh