The French Revolution was perhaps the greatest tragedy in history.

It ushered in an era of:

-violence

-class warfare

-authoritarianism

But France’s faith suffered the most—thousands of priests were executed or exiled as a new atheistic religion was thrust onto the people…🧵

It ushered in an era of:

-violence

-class warfare

-authoritarianism

But France’s faith suffered the most—thousands of priests were executed or exiled as a new atheistic religion was thrust onto the people…🧵

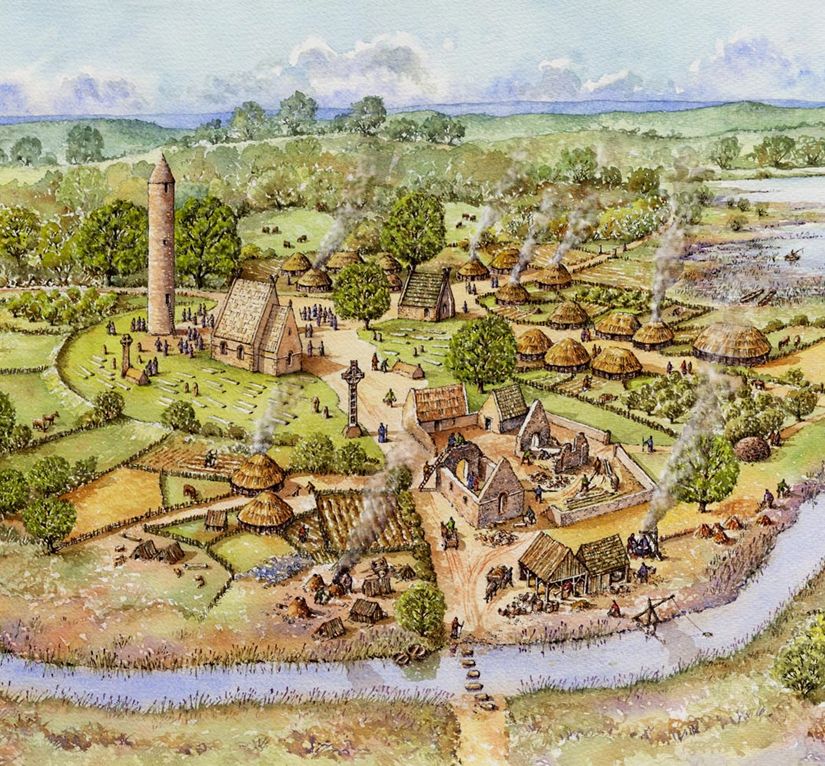

Before the revolution, France and Catholicism were inseparable.

France was called the “eldest daughter of the Church” since Frankish king Clovis I accepted the Catholic faith in the early 6th century.

France was called the “eldest daughter of the Church” since Frankish king Clovis I accepted the Catholic faith in the early 6th century.

In the 18th century, the vast majority of the population were Catholic, and it was the only religion officially allowed in the kingdom.

The church influenced all aspects of French life—hospitals, education, and birth/death records were controlled by the Church.

The church influenced all aspects of French life—hospitals, education, and birth/death records were controlled by the Church.

But the Church became a central target of the French Revolution in 1789.

The monarchy owed its legitimacy to the Church, so by destabilizing the Church, revolutionaries were able to pull out the rug from under the monarchy—the two went hand in hand.

The monarchy owed its legitimacy to the Church, so by destabilizing the Church, revolutionaries were able to pull out the rug from under the monarchy—the two went hand in hand.

Initially, as outlined in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of 1789, revolutionaries sought a libertarian approach to religion:

“No one may be disturbed for his opinions, even religious ones, provided that their manifestation does not trouble the public order...”

“No one may be disturbed for his opinions, even religious ones, provided that their manifestation does not trouble the public order...”

Anti-Catholic sentiment intensified though, and the National Constituent Assembly, France’s acting government, ordered the seizure of properties and land held by the Catholic Church, selling them to fund the new revolutionary currency.

And later the assembly passed the "Civil Constitution of the Clergy," a law that subordinated the Catholic Church in France to the secular government.

Though it was rejected by the pope, it divided the clergy into jurors, who accepted the law, and non-jurors, who rejected it.

Though it was rejected by the pope, it divided the clergy into jurors, who accepted the law, and non-jurors, who rejected it.

Non-juring priests were viewed as counter-revolutionaries, and were sentenced to death on sight.

Hundreds of Catholic priests were executed while thousands more were banished from the country. Faithful Catholics that remained were left without leadership or the sacraments.

Hundreds of Catholic priests were executed while thousands more were banished from the country. Faithful Catholics that remained were left without leadership or the sacraments.

Eventually anti-Catholic sentiment gave way to a frenzied anti-Christian sensationalism.

Crosses, church bells, statues, and iconography were destroyed in an attempt to secularize society.

Crosses, church bells, statues, and iconography were destroyed in an attempt to secularize society.

Under the leadership of figures like Joseph Fouché, revolutionaries removed crosses from graveyards and declared that all cemeteries must bear only one inscription:

“Death is an eternal sleep.”

“Death is an eternal sleep.”

Instead of Christianity, revolutionary leaders thrusted a new, atheistic religion on the French people: the Cult of Reason.

Though hard to pin down, it centered around the core principles of Reason, Liberty, Nature, and the revolutionary spirit.

Though hard to pin down, it centered around the core principles of Reason, Liberty, Nature, and the revolutionary spirit.

Promoted by Antoine-François Momoro, it was an assortment of various ideas based on materialist philosophy.

In practice, it was little more than an avenue for the state to promote anticlericalism and wealth confiscation.

In practice, it was little more than an avenue for the state to promote anticlericalism and wealth confiscation.

The Cult of Reason even had its own places of worship—the churches of France were converted into modern “Temples of Reason,” where Christian altars were dismantled and transformed into altars to Liberty.

And ceremonies were held to celebrate the new religion…

And ceremonies were held to celebrate the new religion…

The largest ceremony was held at Notre Dame in Paris. The inscription "To Philosophy" was carved over the cathedral's doors, and girls dressed in white danced around a costumed “Goddess of Reason,” who was played by Momoro’s wife.

She was said to have dressed “provocatively.”

She was said to have dressed “provocatively.”

The Cult of Reason was later supplanted by another state-imposed religion, the Cult of the Supreme being, but these were both ultimately banned by Napoleon.

Napoleon allowed the Church back into France in 1801, but the damage the revolution caused to the Faith was incalculable

Napoleon allowed the Church back into France in 1801, but the damage the revolution caused to the Faith was incalculable

The removal of the Catholic Church completely transformed French society, from the dissolution of the monarchy to the restructuring of basic institutions like education and administrative government.

Though not as stark as during the French Revolution, the same materialist principles dominate mainstream thought in Western countries today just as faith is being discarded.

Will the West undergo the same restructuring that France went through when it abandoned its faith?

Will the West undergo the same restructuring that France went through when it abandoned its faith?

If you enjoyed this thread and would like to join the mission of promoting western tradition, kindly repost the first post (linked below) and consider following: @thinkingwest

https://twitter.com/thinkingwest/status/1799088683200417911

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh