In 1896, Brooks Brothers president John E. Brooks—grandson to company founder Henry Sands Brooks—saw British polo players wearing something peculiar. Their collar points had little buttons that fastened to their body, preventing them from flying up while riders were in play.

Enamored with the design, Brooks sent a sample to his store in Manhattan with instructions to have the collar copied. Hence, the birth of Brooks Brothers' "polo collar"—also known as the button-down. The design was first put on pullover shirts, then coat-front varieties.

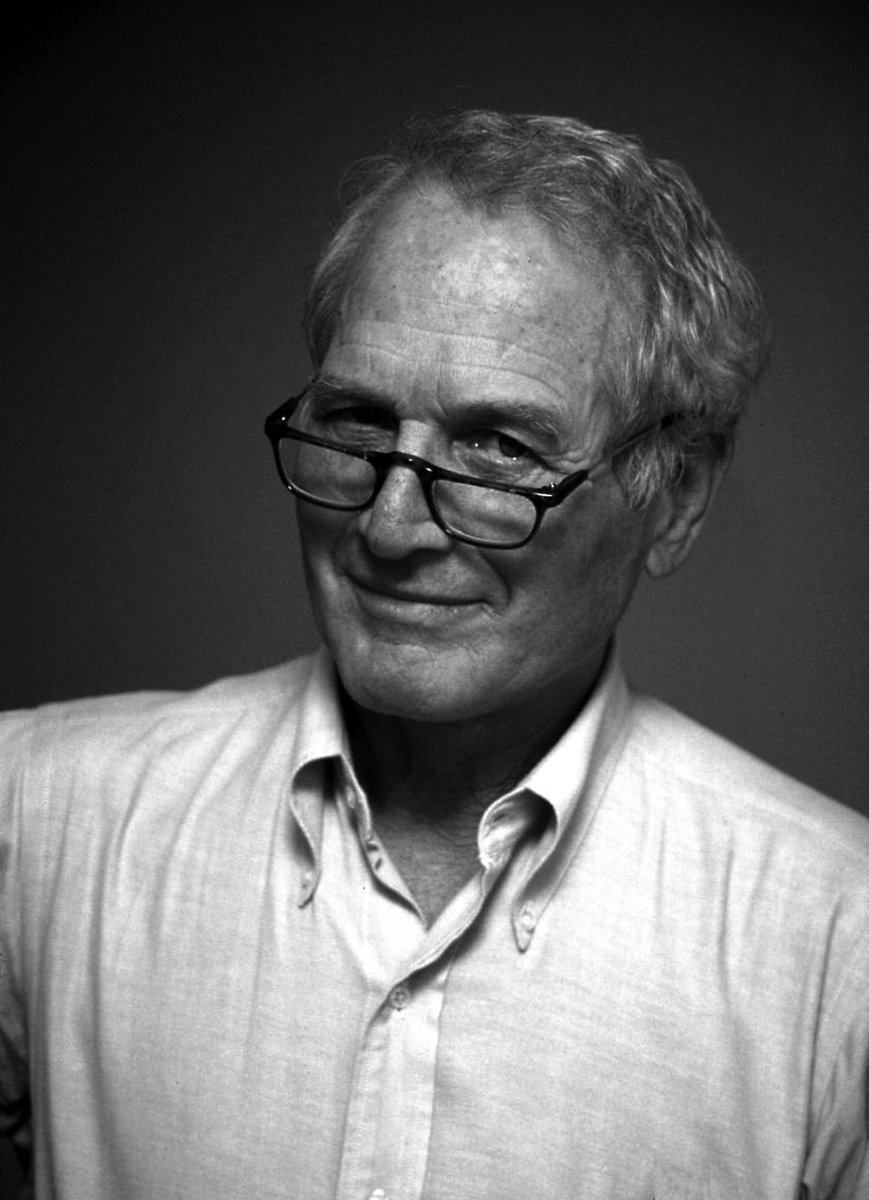

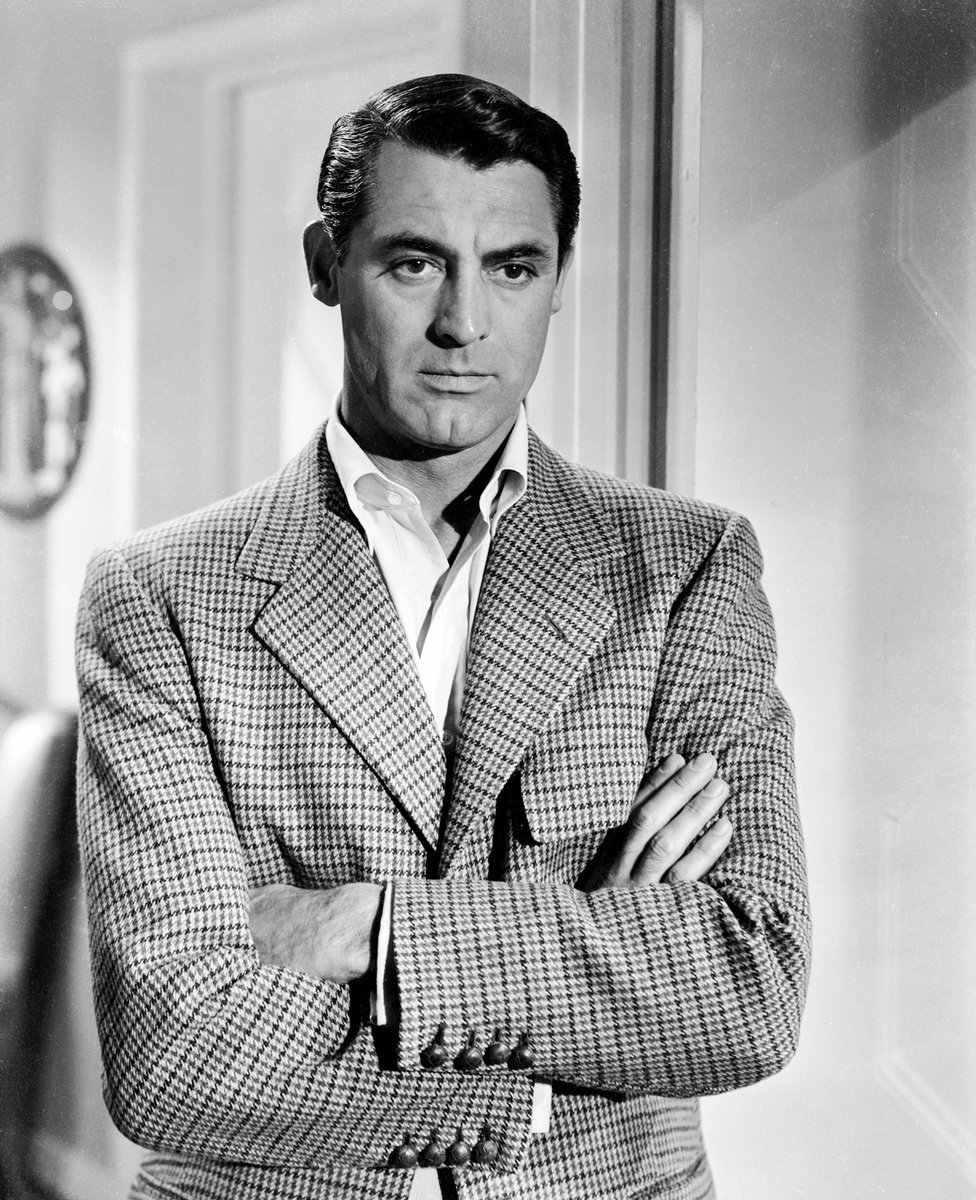

The shirt was an instant classic. By 1915, the button-down collar was a wardrobe staple for young men at Ivy League colleges. By mid-century, it spread West. Style icons Paul Newman, Miles Davis, and Gianni Agnelli were regularly seen in Oxford cloth button-downs (OCBDs).

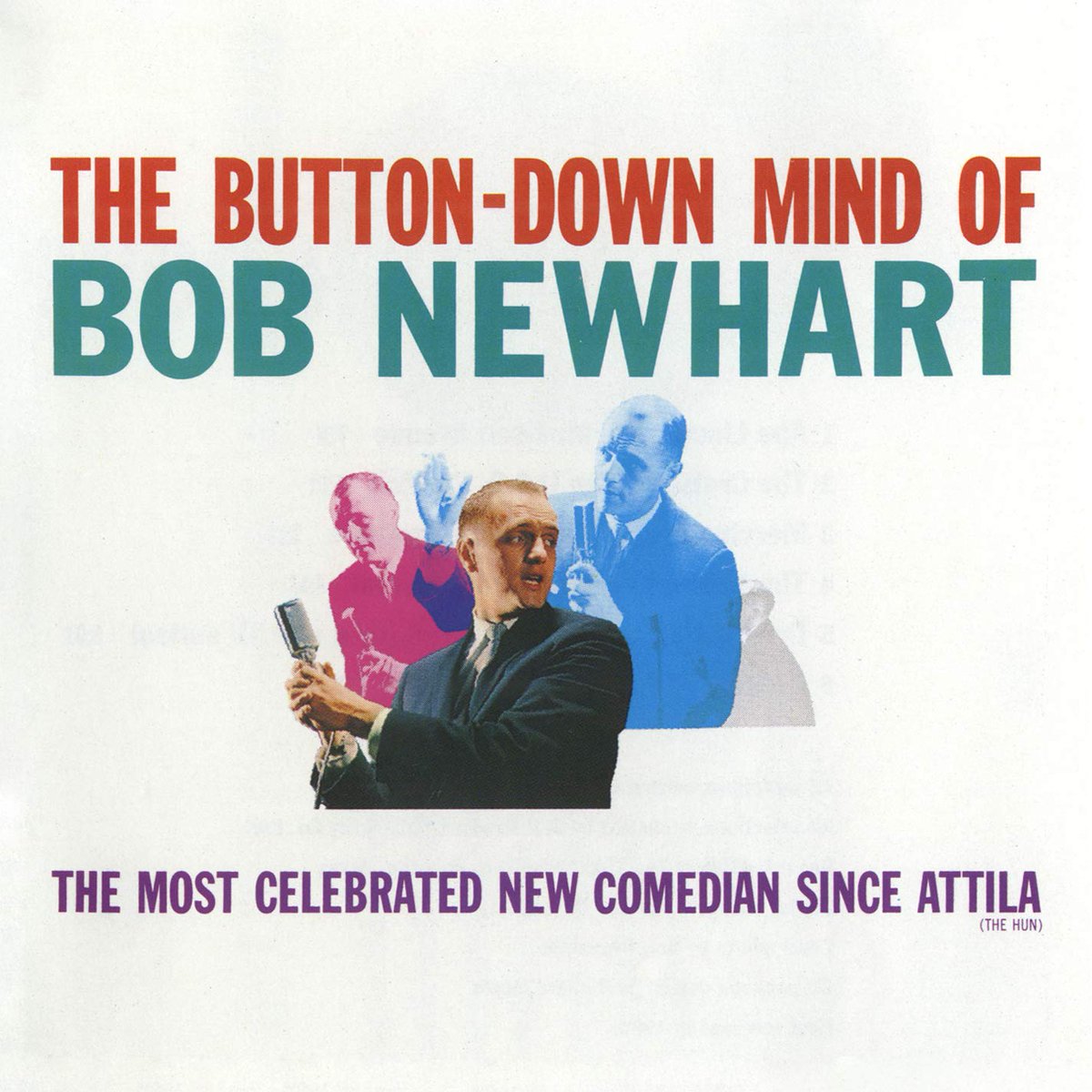

The style became a symbol of all that's good: casualness, youth, education, trustworthiness, dependability, and sport. Americans wore them on weekdays and weekends, with or without a tie, with suits or casualwear. Bob Newhart even named his first record after them.

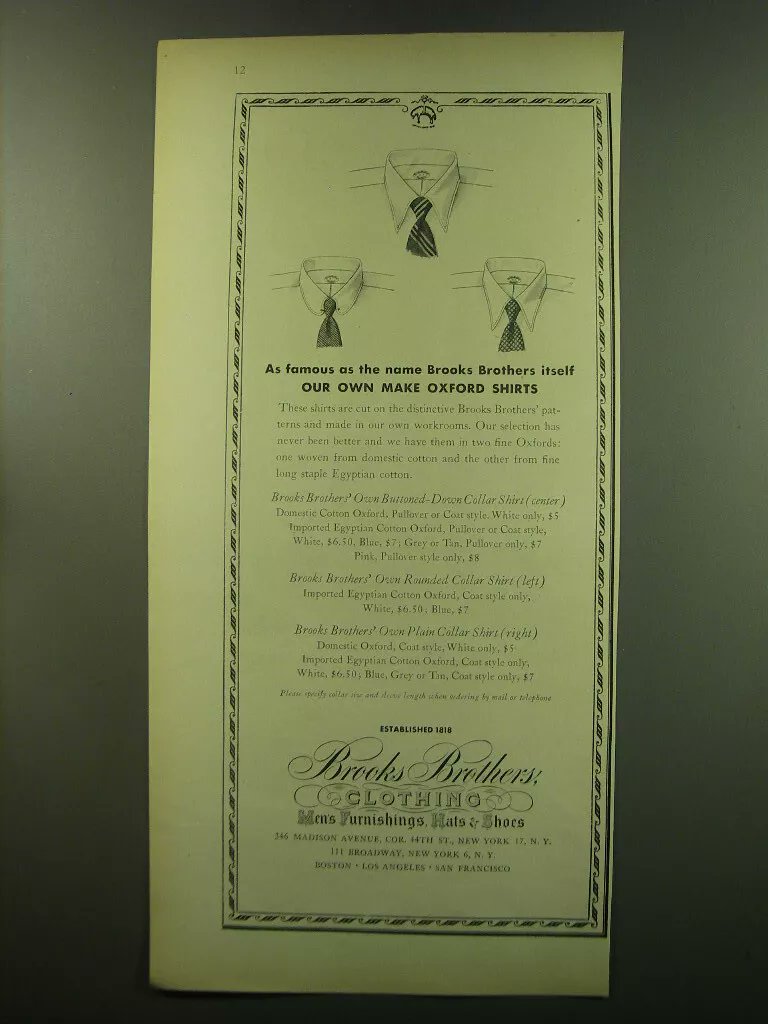

In 1949, Brooks Brothers charged about $7 for their button-down shirts, depending on the fabric and style. In today's dollars, that translates to about $90. During this time, the shirt almost never went on sale. Thousands of clothiers copied it, making it an American classic.

For guys who are really into tailoring, OCBDs hold a special place in menswear history because they symbolize something special about American style: that slightly messy, deshabille character that makes tailoring look more natural and charming.

When the collar is made correctly, the collar leaf will form a soft roll like an angel's wings. IMO, the collar is also best when it's unlined so that it rumples when you move. This expresses the casual nature that has always been at the heart of American style.

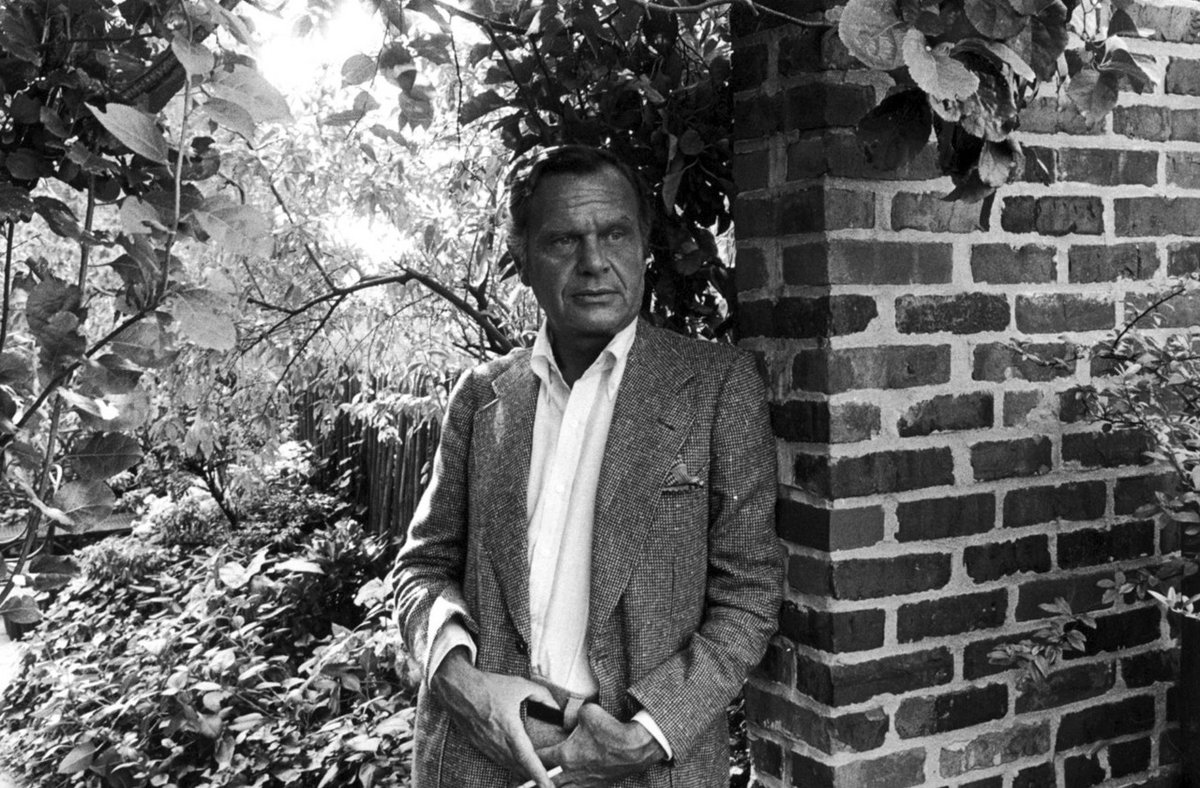

Of course, this assumes you can find a collar that has been cut correctly. Just as men's suits, shirts, and trousers have shrunk in the last 20 years, so have their collars. When a collar is too small, it doesn't exhibit that charming roll. Compare:

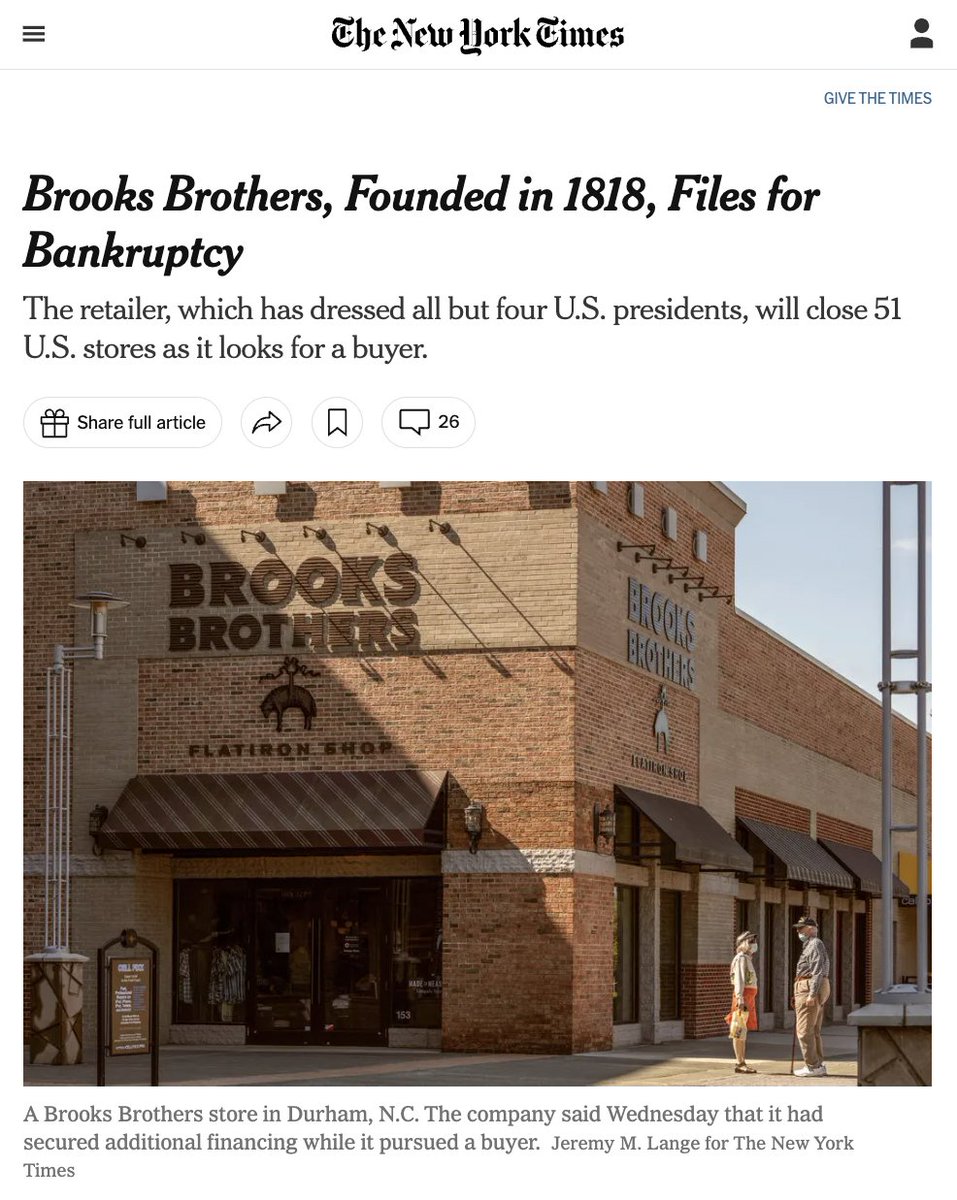

In 2020, Brooks Brothers filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. The company cited the pandemic, but the real reasons involved long-term changes in the clothing market, a set of questionable business decisions, and a complex network of real estate deals that locked them into bad stores

When Brooks Brothers filed for bankruptcy, I interviewed several of its former executives. One told me that the company derived about 27% of its sales from non-iron button-up shirts alone—and this is just a fraction of its shirt business.

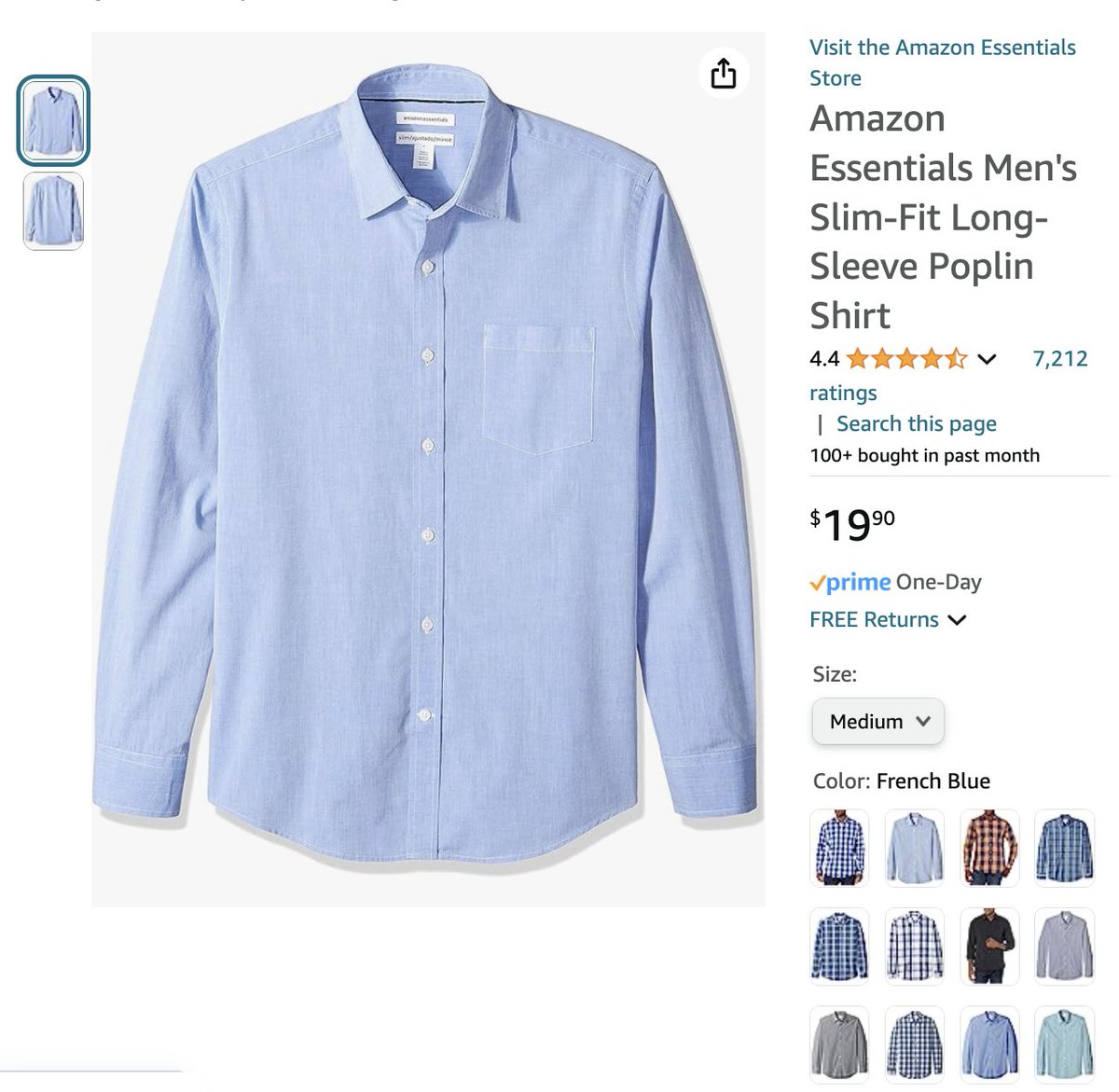

This shocking statistic reveals the decline of big-ticket items such as suits and sport coats (and the importance of non-iron fabrics in the company's business). I was also shocked when he said the company sees its competitors in brands like UnTuckit and Amazon.

In the 1980s, Brooks Brothers' OCBDs went on sale once a year—after Christmas—and only for a meager discount. As the company faced headwinds, it created lower-tier lines at outlet stores and increasingly more sales within the mainline.

I asked this executive how it was possible that the most important company in American men's tailoring could not distinguish its button-downs—which it invented—from generic $20 shirts on Amazon. "That's the million-dollar question," he said.

When Brooks Brothers filed for bankruptcy, it shed a few of their American factories (a credit to former CEO Claudio Del Vecchio, who held onto them under immense pressure to offshore even more of the company's production during the period from 2001 to 2020)

One of these was the Garland Shirt Company in North Carolina, which made Brooks Brothers' iconic button-downs. The shuttering of this factory meant the loss of 150 jobs in this small Sampson County town. They were the town's largest employer.

Out of this rubble was a small beam of hope: the emergence of the Garland Apparel Group, which sought to rescue the operation. They bought the factory and brought back many of the employees—109 out of the 150. In 2022, Sampson Independent said business was "bursting at the seams"

A few months ago, the newspaper published an update: "Factory eyes next chapter. Low orders led to closure; next tenant sought." There are discussions to pass it on to a new owner, although I don't know the state of things. If it closes, it will be a loss of a 70-year-old factory

Kenneth Ragland, the managing partner for Garland Apparel Group, told the newspaper bluntly: “Lots of people talk about Made in the USA as being so necessary, but when the rubber meets the road, most Americans want cheap goods, which do not make it easy for US firms to survive.”

Over time, Brooks Brothers had to charge a little more for their shirts, although some of this was offset by discounts. In 1949, they were $90. In 2019, I think they were $150 or so, but often discounted to $100.

I don't know their manufacturing costs, but I do know the cost of making a shirt at other US factories. Labor alone is about $35/ shirt. Fabric can range from $3-9 per yard. You need 1.75 yards to make a shirt. So the cost is about $45/ shirt.

This is for a small run. Brooks Brothers would get a cheaper price because of volume. But the estimated costs here also don't include the price of pattern making, sourcing, sample making, marking, or grading. My only point is that $100-150/ shirt is not crazy for made-in-USA.

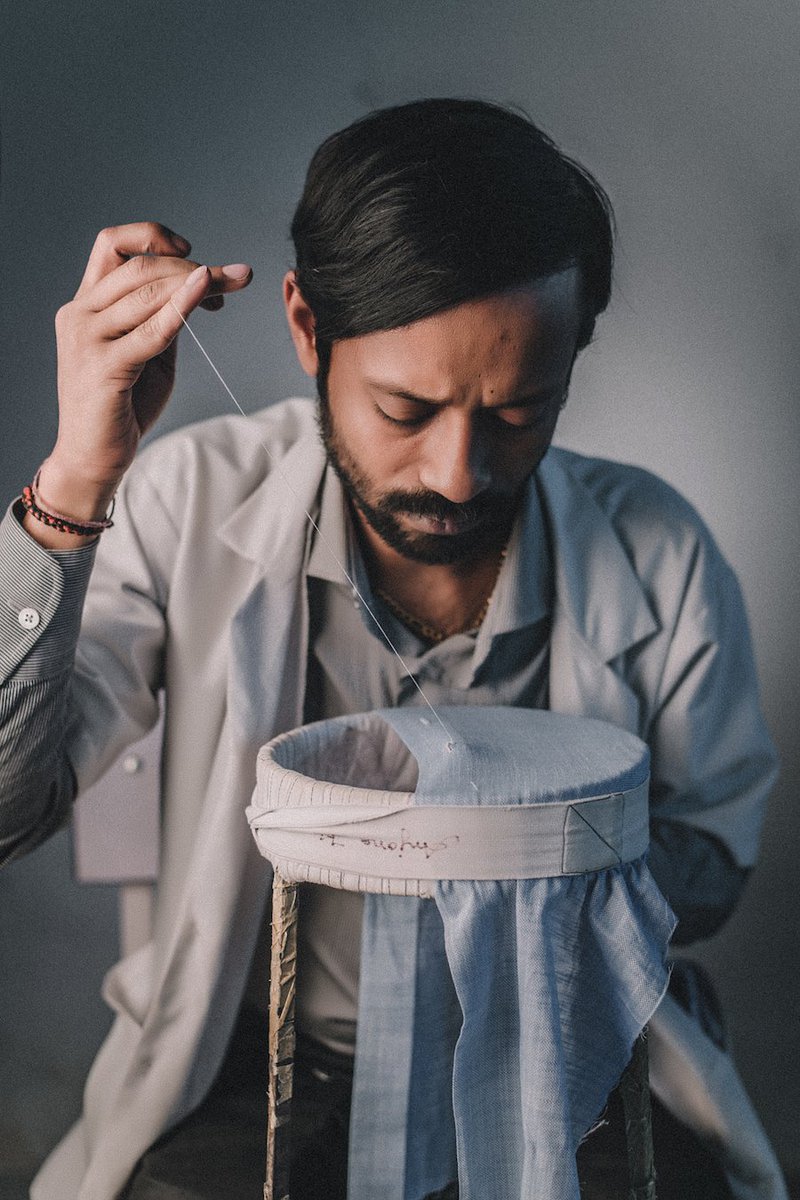

Are shirts made in low-cost countries necessarily worse? No, not necessarily. Some may, in fact, be better in terms of "quality." The finest ready-to-wear shirts I've seen are from 100 Hands in India. There is a tremendous amount of handwork, although you pay for it (~$400)

There's nothing special about American hands vs. foreign ones. You can get a great OCBD made abroad (most of mine are made by Ascot Chang in Hong Kong). But I do think there's something special about a Brooks original made in the USA. It would be a shame if it disappeared.

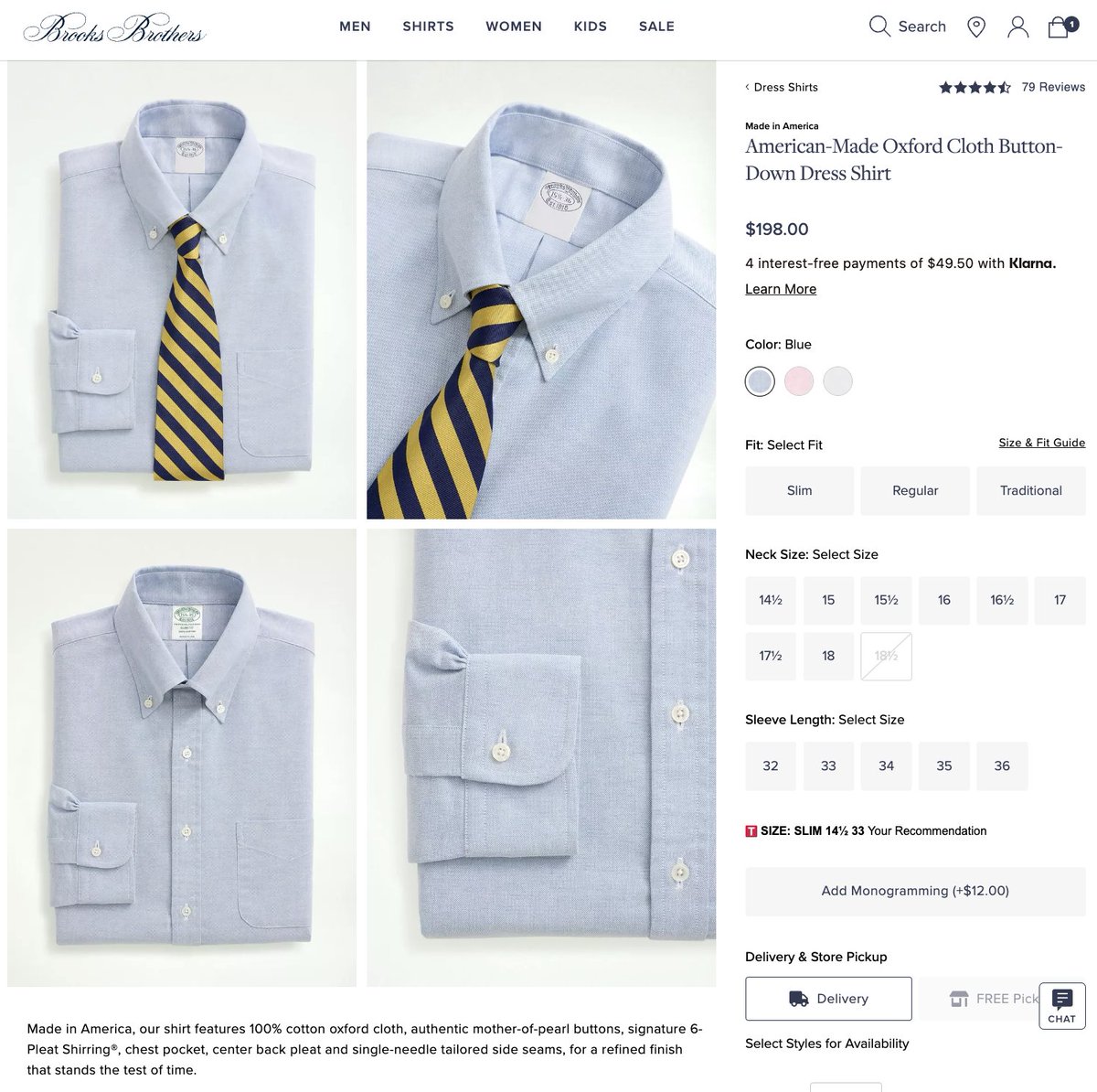

Today, you can still get a Brooks Brothers button-down, but it costs a little more: $198.

Some links if you want to read more:

A history of OCBDs that I wrote in 2013 🔗:

My story on why Brooks filed for bankruptcy 🔗: putthison.com/tag/the-oxford…

dieworkwear.com/2020/07/17/lam…

Some links if you want to read more:

A history of OCBDs that I wrote in 2013 🔗:

My story on why Brooks filed for bankruptcy 🔗: putthison.com/tag/the-oxford…

dieworkwear.com/2020/07/17/lam…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh