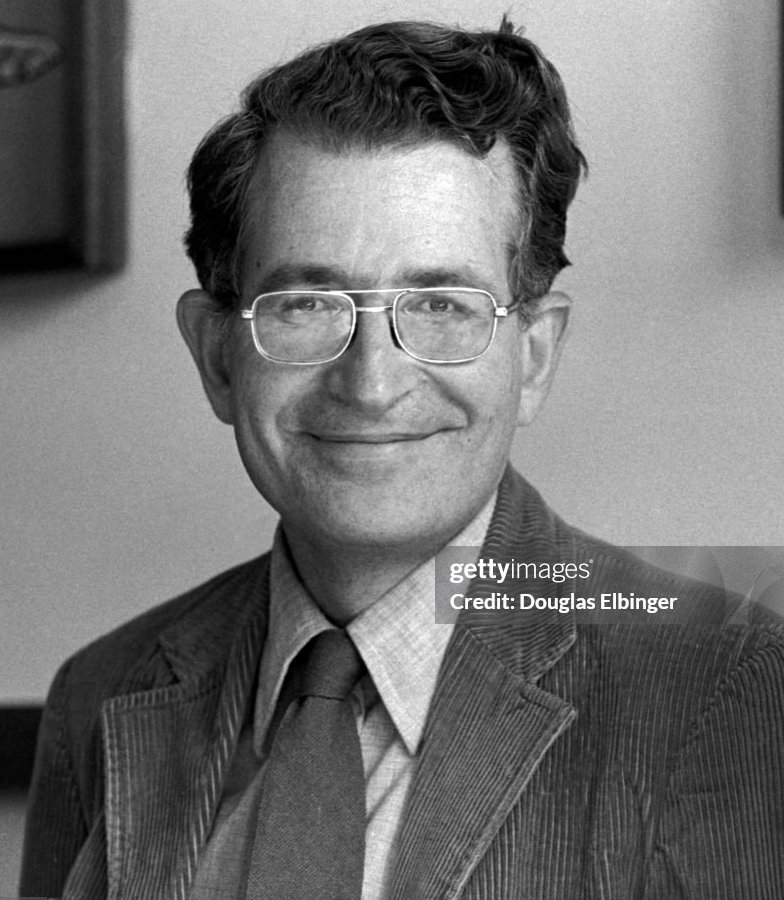

People mistake the notion of taste. Whatever one thinks of Chomky's worldviews, his style is very much a reflection of him as a person: a radical leftist academic who bought tailored clothing during the 1950s and 60s, which gives him a certain familiarity. 🧵

https://twitter.com/ggreenwald/status/1803532765532410322

Please note that in the following thread, I am not placing any value judgment on the term "Good Taste." I am only talking about it in the sociological sense. Every group has its own notion of taste, but only one gets privileged. Also, I'm not here to debate Chomsky's politics.

In his book Distinction, Pierre Bourdieu notes that the notion of Good Taste is nothing more than the preferences and habits of the ruling class. In American culture, this class is represented by the likes of William Buckley and George Plimpton.

Chomsky didn't grow up as a member of this class—he's a son of working-class Jewish immigrants—but he's certainly familiar with it, if only through proximity. After all, he debated Buckley, who famously threatened to punch him in the face, in 1969 on the show Firing Line.

Chomsky was born in 1928, which means he would have started shopping for tailored clothing in the late 1940s/ early 1950s. During this period, there were still one-stop-shop clothiers with tailors who could help you build a wardrobe.

So when you see earlier photos of him, it's not surprising that he dressed pretty well—his proximity to Good Taste and access to decent stores meant that he did not look terrible (true of many men of his generation).

But there are always things that betray his social position: his use of mid-calf socks, instead of over-the-calf socks, with tailored clothing. The occasionally questionable tie (this striped cotton knit tie is pretty ugly and obvs driven by the fashion of that era)

But even in his older years, you will not see him in the truly awful tailoring that's common today, partly because he grew up during a period when men wore tailoring more regularly and had access to clothiers who guided them. He knows when things are too tight.

Some things hint at his counter-cultural leanings, such as the Army jackets that student protestors pressed into subversive services in the 1960s and '70s. And Clarks Wallabees, which were once associated with intellectuals and progressives.

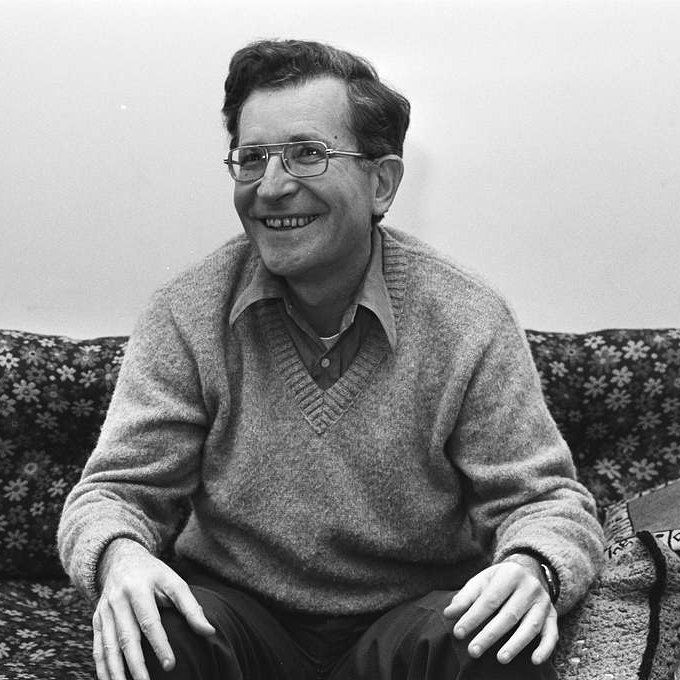

And look at the types of sweaters he's worn throughout his life. In the original thread, one commentator called these sweaters "generic." Perhaps. But they are Shetlands and Shaker knits, commonly sold in stores such as Brooks Brothers and J. Press.

These are not like the smooth merino sweaters you see at the mall. If you look at the history of well-dressed men before 1980, you'll notice that the knits often have a spongey texture.

I don't know what Chomksy specifically found offensive about this tie. But from the photo, it appears a bit shiny—perhaps made from satin. In this framework of "Good Taste," satin ties are considered a bit vulgar, especially outside of dinner suits.

Note that I am not trying to draw any comparison between Trump and Greenwald beyond neckwear. But to give an example, Trump has made shiny ties a style signature—a bold, brash, wealthy businessman who lives in a gold home and wears shiny ties. It's the opposite of "Good Taste."

A more tasteful, neutral tie would be something like a regimental stripe in repp silk or Irish poplin. Matte, tasteful, quiet.

Greenwald is also a product of his generation. He was born in 1967, during the waning years of the coat-and-tie. By the time he would have shopped for himself as a young adult, the market was already chaotic, and notions of Good Taste were less relevant.

That class has almost no social relevance today. The centers of cultural, political, and financial power have shifted away from Plimpton and Buckley and towards Musk and Bezos.

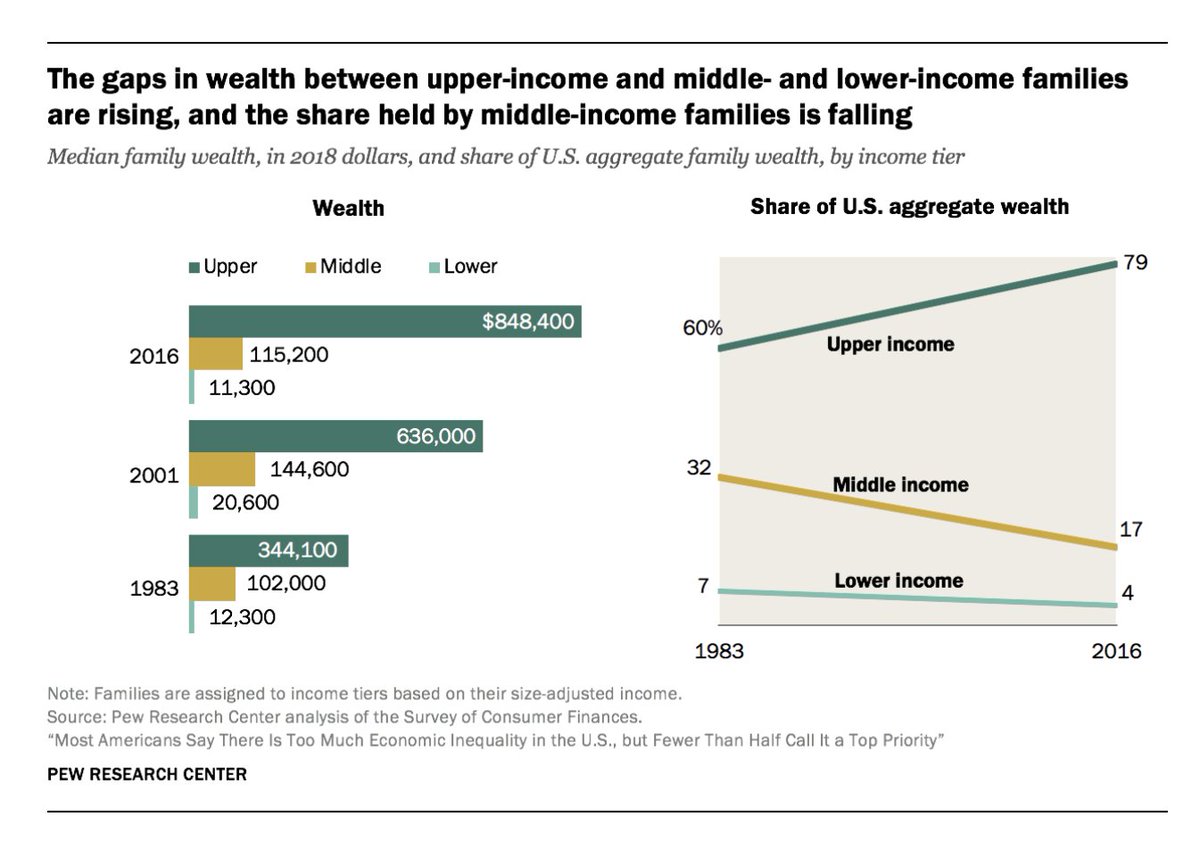

There's some irony in that, as the upper classes have dressed down to look more middle-class, income inequality has mostly grown every decade since the 1980s.

In any case, to bring this back to ties, I don't find it surprising that a man who grew up with tailored clothing might have an opinion on ties. And one does not need to be Anna Wintour or be dressed "fashionably" to have a sense of taste.

To flatten Chomsky's style to a "guy who wears generic sweaters" is to miss the nuances in how men's style expresses deeper things. Some irony is how a self-professed anarcho-syndicalist and libertarian socialist upheld old notions of ruling-class taste.

Whoops, in my haste, I included the wrong chart on income inequality. The relevant charts are on this Pew Research page.

🔗: pewresearch.org/social-trends/…

🔗: pewresearch.org/social-trends/…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh