How should we tax capital gains due to rising asset prices? On realization? On accrual? Or should we perhaps tax wealth?

The existing public finance literature has a big hole making it unsuitable for thinking about these issues: it doesn't model asset prices!

🧵 on a new paper:

The existing public finance literature has a big hole making it unsuitable for thinking about these issues: it doesn't model asset prices!

🧵 on a new paper:

We “put the ‘finance’ into ‘public finance’”, meaning that we study optimal redistributive taxation with changing asset prices.

Joint work with Mark Aguiar and @Florian_Scheuer

Paper here:

Slides here: benjaminmoll.com/PFPF/

benjaminmoll.com/PFPF_slides/

Joint work with Mark Aguiar and @Florian_Scheuer

Paper here:

Slides here: benjaminmoll.com/PFPF/

benjaminmoll.com/PFPF_slides/

This is important because there have been a number of recent policy proposals to tax wealth or unrealized capital gains

Just 3 days ago @gabriel_zucman made one for @g20org

When does that make sense?

Just 3 days ago @gabriel_zucman made one for @g20org

When does that make sense?

https://x.com/gabriel_zucman/status/1805603448857182708

An important related question is: what is income? And therefore what's a good tax base?

The standard public finance answer goes back to 1920s & 30s: "Haig-Simons income" which includes unrealized capital gains

When does that income concept make sense? en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haig%E2%8…

The standard public finance answer goes back to 1920s & 30s: "Haig-Simons income" which includes unrealized capital gains

When does that income concept make sense? en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haig%E2%8…

This matters: for example, @gregleiserson and @dannyyagan calculate that the 400 wealthiest U.S. families paid an average tax rate of only 8.2% by including unrealized capital gains in the tax base.

whitehouse.gov/cea/written-ma…

whitehouse.gov/cea/written-ma…

Other important related issues include:

- the wealthy borrowing against appreciating assets rather than selling

- "stepped-up basis" for inherited assets

- "buy, borrow, die" tax avoidance strategies

See the most recent @TheEconomist for a good article

- the wealthy borrowing against appreciating assets rather than selling

- "stepped-up basis" for inherited assets

- "buy, borrow, die" tax avoidance strategies

See the most recent @TheEconomist for a good article

https://x.com/TheEconomist/status/1804513679800463387

On to our paper:

When we "put the finance into public finance", we adopt the modern finance view that asset prices fluctuate not only because of changing cash flows, but also due to other factors (“discount rates”)

This is Shiller's famous paper

aeaweb.org/aer/top20/71.3…

When we "put the finance into public finance", we adopt the modern finance view that asset prices fluctuate not only because of changing cash flows, but also due to other factors (“discount rates”)

This is Shiller's famous paper

aeaweb.org/aer/top20/71.3…

Our question is: how should the optimal tax system responds to changes in asset prices, starting from some baseline (e.g. a steady state)?

Our main findings: optimal redistributive taxes

(i) generally differ from the case with constant asset prices

(ii) depend on the sources of asset-price changes

Taxing wealth or unrealized capital gains *can* be optimal. But only in extreme knife-edge cases.

(i) generally differ from the case with constant asset prices

(ii) depend on the sources of asset-price changes

Taxing wealth or unrealized capital gains *can* be optimal. But only in extreme knife-edge cases.

Whenever asset prices fluctuate beyond movements due to cash flow changes, taxes must target realized trades, i.e. sales and purchases not asset holdings.

A tax combination that works in general (even if it's all cash flows): realization-based capital gains + dividend taxes.

A tax combination that works in general (even if it's all cash flows): realization-based capital gains + dividend taxes.

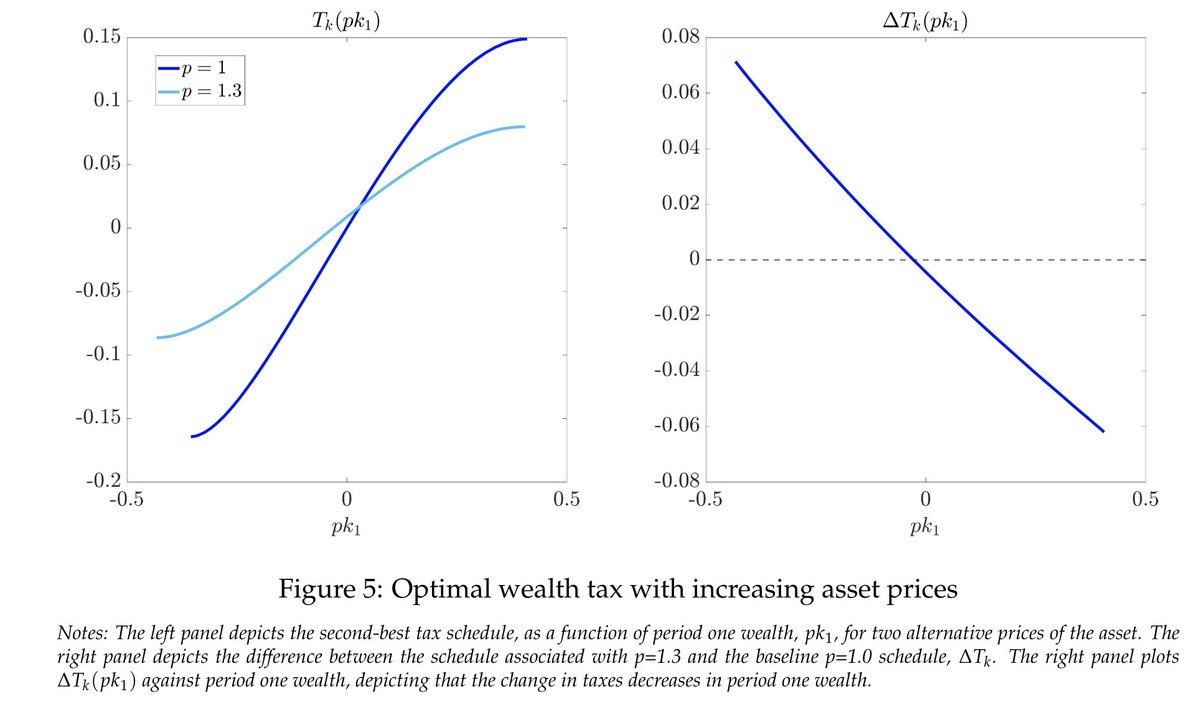

Taxes that are optimal in environments with constant asset prices may cease to be optimal, or change in counterintuitive ways, when asset prices fluctuate.

Example: a wealth tax may be optimal with constant asset prices. But when prices move, its progressivity must change...

Example: a wealth tax may be optimal with constant asset prices. But when prices move, its progressivity must change...

In extreme examples, optimal taxation may even prescribe tax cuts for the wealthiest when asset prices rise.

The key intuition is that rising asset prices primarily benefit asset sellers not asset holders --> transactions matter!

This is true except in some knife-edge cases which are precisely those cases in which taxing Haig-Simons income or wealth is optimal.

This is true except in some knife-edge cases which are precisely those cases in which taxing Haig-Simons income or wealth is optimal.

https://x.com/ben_moll/status/1549356986072027136

A useful stepping stone for understanding our results is the idea of Slutsky compensation you may remember from your study of income and substitution effects.

In the first-best case, optimal lump-sum taxes essentially Slutsky-compensate gains & losses from changing asset prices.

In the first-best case, optimal lump-sum taxes essentially Slutsky-compensate gains & losses from changing asset prices.

While our formula for optimal redistributive taxes is reminiscent of realization-based capital gains taxation systems observed in practice, it also differ in important ways.

E.g. it prescribes compensating "purchasing losses" and taxing *net* rather than *gross* transactions.

E.g. it prescribes compensating "purchasing losses" and taxing *net* rather than *gross* transactions.

An important one is the wealthy borrowing against appreciating assets, often with the aim of taking advantage of the "stepped-up basis" for bequeathed assets as part of a "buy, borrow, die" tax avoidance strategy.

@TheEconomist has a good example

economist.com/finance-and-ec…

@TheEconomist has a good example

economist.com/finance-and-ec…

Our results show that, by itself, the wealthy borrowing against appreciating assets is not the issue.

The real issue is the "stepped-up basis" which should be eliminated and replaced by a "carry-over basis" as already practiced in a number of countries including 🇩🇪🇮🇹🇯🇵

The real issue is the "stepped-up basis" which should be eliminated and replaced by a "carry-over basis" as already practiced in a number of countries including 🇩🇪🇮🇹🇯🇵

Absent stepped-up basis, the wealthy would still benefit from borrowing against high-return assets with lower-interest loans.

But this is just like *any* leveraged investment, e.g. homeowners investing in the stock market rather than repaying their mortgage --> not tax avoidance

But this is just like *any* leveraged investment, e.g. homeowners investing in the stock market rather than repaying their mortgage --> not tax avoidance

Some things are also (still) missing from the paper, e.g. a satisfactory treatment of the "lock-in effect" of realization-based capital gains taxation emphasized in the public finance literature

To summarize our results, it is useful to juxtapose them with the following naïve intuition implicit in proposals for wealth taxes or taxes on unrealized capital gains: "when the value of Jeff Bezos’ Amazon stocks doubles so should his tax liability."

edition.cnn.com/2021/10/26/opi…

edition.cnn.com/2021/10/26/opi…

Our results show that this intuition is, in general, incorrect. Optimal taxes instead generally depend on (i) whether Bezos sells his Amazon shares and (ii) whether and by how much cash flows, here Amazon’s profits,

increase.

increase.

To be clear, we do not have much to say about optimal tax *rates* on the wealthy. These may well be high

But key point: subject to eliminating loopholes like basis step-up, the existing tax *structure* with realization-based capital gains + dividend taxes is probably not so bad!

But key point: subject to eliminating loopholes like basis step-up, the existing tax *structure* with realization-based capital gains + dividend taxes is probably not so bad!

p.s. in case you're in Barcelona for the @SEDmeeting conference, you can listen to my co-author Mark presenting our paper this afternoon:

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh