The James Webb Space Telescope has started capturing images of galaxies so far away that they are causally disconnected from the Earth — nothing done here or there could ever interact. 🧵

1/

1/

The latest of these, JADES-GS-z14-0, was discovered at the end of May this year. It is located 34 billion light years away — almost three quarters of the way to the edge of the observable universe.

2/

2/

The light we are capturing was released by the galaxy about 13.5 billion years ago — just 0.3 billion years after the Big Bang. So we are seeing a snapshot of how it looked in the early days of the universe.

3/

3/

Because the space between us is stretching, the current distance to the galaxy is 15 times larger than it was when the light began its journey towards us. That's how it can be 34 billion light years away when the light has only travelled for 13.5 billion years.

4/

4/

The expansion of space makes it hard for anything, even light, to cross the vast gulfs between distant galaxies, as the distance you need to cross keeps growing. Because the expansion is accelerating, eventually the remaining distance grows too fast to ever cross.

5/

5/

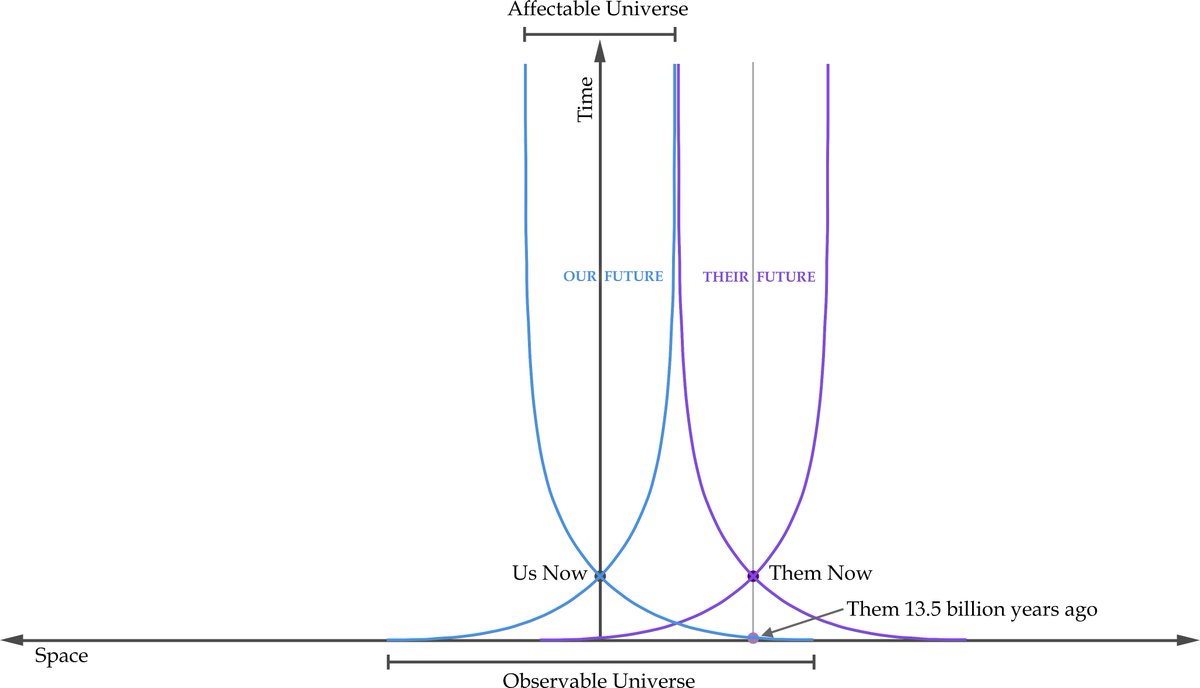

If we shine a torch up at the night sky, some of the photons released will eventually leave our galaxy and travel for a vast distance. They will eventually be able to reach any galaxy that is currently within 16.5 billion light years of us.

6/

6/

I call this region that we can affect 'The Affectable Universe', and in many ways it is the twin to the Observable Universe. Each year, more galaxies slip beyond our reach, as a photon released next year will no longer be ever able to reach them.

7/

7/

JADES-GS-z14-0 is well beyond the edge of the affectable universe. Nothing we send out can ever reach it or affect it.

We've seen galaxies beyond this distance for a long time. Many of the smaller galaxies in the Hubble Deep Field below are forever beyond out reach.

8/

We've seen galaxies beyond this distance for a long time. Many of the smaller galaxies in the Hubble Deep Field below are forever beyond out reach.

8/

But events here and contemporaneous events in those small galaxies *can* interact — if being in both galaxies set off towards each other at near the speed of light, they could eventually meet in the middle.

9/

9/

Or if we both sent signals, an alien civilisation in the middle could receive both and combine them. In other words, it is still possible to causally interact with each other.

10/

10/

This is also what we saw with the star 'Earendel' — the first individual star to be identified that was beyond our affectable universe.

11/

11/

https://x.com/tobyordoxford/status/1562144747522850816

But JADES-GS-z14-0 is slightly more than *twice* as far as the edge of the affectable universe. So the affectable universe around us and the affectable universe around them don't overlap at all. So there is no longer a way to interact at all.

12/

12/

Of course, we can still see these baby photos of their galaxy, but no matter how long we wait, we'll never see them grow up to our current age. If we waited, we'd see the evolution of their galaxy slow down asymptotically and never get to be 13.8 billion years old.

13/

13/

Of course, they'd keep getting older, but the 'postcards' (photons) they send us get delayed longer and longer by the expanding distance they have to cover, so come in less and less frequently, and recent postcards will never arrive.

14/

14/

You can find out much more about this in my paper on The Edges of Our Universe, described here:

15/15

15/15

https://x.com/tobyordoxford/status/1379357627134705665

So far the JWST has identified 3 such galaxies that are twice as far as the edge of the affectable universe (i.e. more than 33.0 billion light years away). You can find them here:

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_t…

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_t…

I've drawn up a scale diagram to show what is happening. The blue lines are our past and future light cones, the purple lines are their's.

For the first 300 million years, they were in our past light cone, which is why we can see their early stages. Similarly, they (now) could see our spot in the universe at that time, but it was empty, and they can never see the Earth form.

And here is a version with a dashed line showing the last point in time at their location that we will ever see. We will only be able to see the first 5 billion years or so, and never be able to see what they are doing now.

If you were interested in this thread and want to hear more big picture thinking about humanity, its role in the cosmos, and why our own time is crucial in that story, you may be interested in my book, The Precipice.

theprecipice.com

theprecipice.com

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh