A few years ago, I was at Buddh Circuit—India’s only F1 track—and I saw a beautiful GT2RS. Out of curiosity, I used an app to find out who the owner was. It turned out the car was owned by a listed Indian company. Subsequently, I found that the company owns several such cars.

So, when we discuss bad assets, we must decide from whose point of view we are looking at the situation. Those cars have been capitalized in the books of the listed company as fixed assets. Their purchase appears as capex to the stockholders in the cash flow statement, but those “assets” will do nothing for the minority shareholders. They are “good assets” for the users but bad for the minority stockholders.

So, I will focus on the idea of “bad assets, good liabilities” from the point of view of minority shareholders of listed or unlisted companies.

Traditional accounting tells us that our net worth is the surplus of assets over liabilities. The focus of the accountants here is the quantum of the assets and liabilities instead of their quality. Once we start applying our minds to the quality dimensions of assets and liabilities instead of just their quantity, some useful insights are found. I share some here.

So, when we discuss bad assets, we must decide from whose point of view we are looking at the situation. Those cars have been capitalized in the books of the listed company as fixed assets. Their purchase appears as capex to the stockholders in the cash flow statement, but those “assets” will do nothing for the minority shareholders. They are “good assets” for the users but bad for the minority stockholders.

So, I will focus on the idea of “bad assets, good liabilities” from the point of view of minority shareholders of listed or unlisted companies.

Traditional accounting tells us that our net worth is the surplus of assets over liabilities. The focus of the accountants here is the quantum of the assets and liabilities instead of their quality. Once we start applying our minds to the quality dimensions of assets and liabilities instead of just their quantity, some useful insights are found. I share some here.

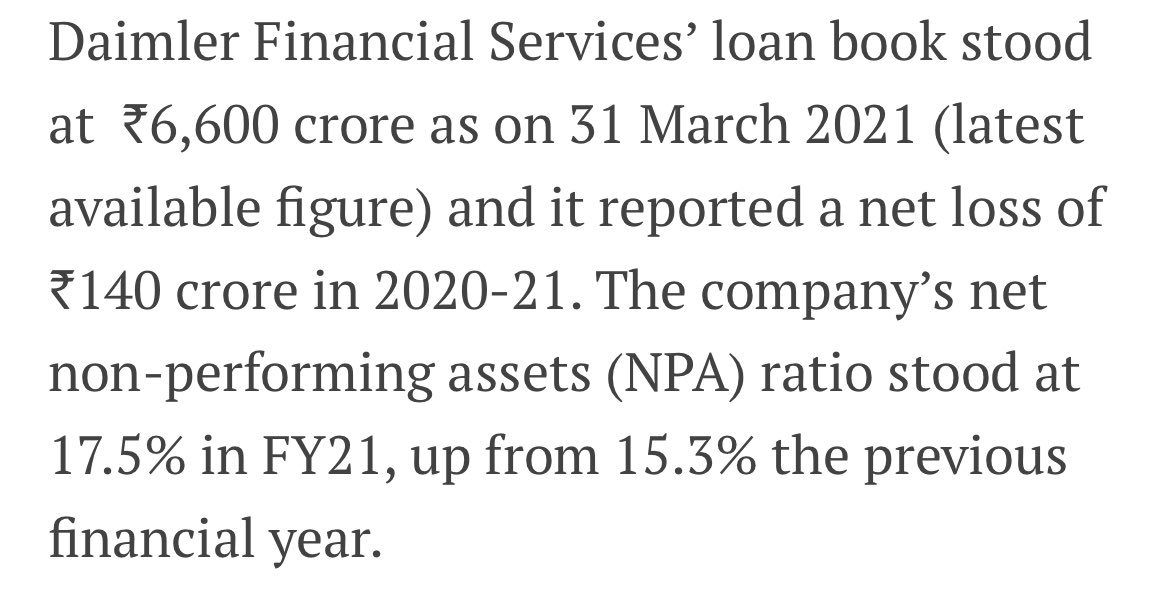

One example of bad assets would be loan losses in a bank but think about this: Loan losses are a cost of doing business in the banking industry. Zero NPAs mean you are not taking enough risk, leaving money on the table. The idea here is not to have zero loan losses but to have a small amount to help you find the right place on the risk spectrum, ranging from being reckless to being too conservative. This is a controversial idea, and not everyone will agree with it.

Bad assets also appear in books but should not be there at all. In other words, fictitious assets. And there are so many of those out there. For example, accounting goodwill arises from paying a large premium over the book value of a bad acquisition. The goodwill will eventually be impaired by the accountants, but that will take a long time. In the meantime, the asset is sitting there, inflating the book value of the common stock.

Another example of a fictitious asset is maintenance capex capitalised, which should have been expensed. This is very common for two reasons: inflation and competitive pressure.

In a fixed capital-intensive business, using original cost accounting in an inflationary environment results in the overstatement of assets because of under-provision for depreciation. When the asset needs to be replaced, the money required to replace it will be far more than what it cost in the first place. So, the correct treatment would be to amortise not the original cost but the replacement cost. Not doing so will result in the overstatement of earnings and the appearance of a fictitious asset on the balance sheet.

Competition in a low-entry barrier, capital-intensive business requires frequent replacement of plant and machinery to keep up with the competition, which is going on a massive capex program. This results in an under-provision of depreciation and overstatement of assets. This is very common and happens in industries where the rate of obsolescence is high. But even here, one has to discriminate between defensive and aggressive strategies.

If a business must spend money on capex to stay in the game because not doing so will result in its going out of business, but doing so will not result in the creation of new earning power but will only help in maintaining current earning power, then that capex is not capex - its an expense. On the other hand, if you are an Nvidia or Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company or Amazon, you are spending money aggressively on research and development or fulfilment centres, then in those situations, those spendings increase their moat so that I would regard them as an asset and not an expense. So context is very important here.

Then there is the case of "white elephants," which are shiny things companies buy that don't do much for the stockholders but cost a lot of money to build/buy and also cost a lot to maintain. Flashy corporate headquarters/jets are one example.

To white elephants, let's add black holes. Losing businesses where you keep throwing good money after bad for all sorts of dumb reasons - that's an example of assets on the books which should have been expensed long ago. Classic example was Buffett's decision to shut down textile operations of Berkshire Hathaway.

Role of litigation. If you can't use an asset because of litigation, which will last decades, how much is it worth? As an aside, here is something I learned from Graham: There are many situations where the value of security largely depends on the outcome of litigation. Generally, the market tends to undervalue a litigated claim as an asset and overvalue it as a liability.

Basically, encumbrances reduce the value of assets as well as liabilities for stockholders. They can come in many forms - read Marty Whitman's Aggressive Conservative Investor on this subject.

Another important point is that what is good today may become bad tomorrow. Just see what has happened to the value of long-term bonds on the assets side of many global investors, as US interest rates have gone from nearly zero to 6%. So, there is a whole category of situations where what is valuable today will not be valuable tomorrow. Another example would be impairment due to disruption. Or, what happened to thermal power projects where power was sold at a fixed price, but input prices (coal from Indonesia) skyrocketed

Another aspect of bad assets is the problem of exit barriers. We think a lot about entry barriers but not much about exit barriers. Some businesses are like Hotel California — you can check in, but you can't check out. For example, loss-making schools, hospitals, or an airline route where the regulators don't allow you to shut down in the community's interests. In such cases, bad assets must be run and maintained — you can't walk away from them easily.

Okay, now let's talk about "good liabilities". Float, obviously, comes to mind. It's other people's money - OPM. Its presence alone reduces the need to borrow or raise equity, creating value for the stockholders. Ask Costco or Amazon (Prime). So, this form of liability is very good. However, just how good it is will depend on many factors.

For example, duration. Insurance float on a 30-year super catastrophe policy must be differentiated from an auto insurance float of one year. Another factor is flexibility in deployment. If there are major restrictions on what you can and can't do with the float money, then its value to stockholders will be curtailed instead of situations without restrictions. Buffett and Munger had no restrictions on using float money of Blue Chip stamps, and they used it to buy Sees Candy. But, stockbrokers can no longer use customers' money in pool accounts, residential real estate developers have to keep customer money (float) in an escrow account and can't use it for other projects, and regulators of insurance companies and banks have norms for deploying float money - they have to park a lot of it in low-income yielding assets - so they have far less flexibility than what Buffett and Munger had in the Blue Chip situation.

Some Indian examples: RITES Limited gets float but has to return the interest on the float money to Indian Railways. That's not the case with Cochin Shipyard and MSTC, and city gas distribution companies.

On CASA, a counter-intuitive view is laid out in Buffett's writing on some of the banks he used to love in his early days. He said that banking is a platform business, so it has to keep customers on both sides of the platform happy. So, it must offer good (high) deposit rates and attractive (low) interest rates on customer loans. He also wrote that deposits are far more sticky than cheap float money in non-interest-bearing accounts. While deposit money costs more, it's long-term and sticky. It reduces asset-liability mismatch, and keeping customers happy on both sides of the balance sheet creates a more durable business. He cites the example of M&T Bank, which should be studied by investors. Their letters are fantastic. In Buffett's world, a bank would be run like M&T Bank - offers good rates on deposits and attracts good customers on the other side of the balance sheet, so loan losses are very tiny. Still, the place is run so frugally that the cost-to-income ratio is very small compared to the competition, and the ROEs are excellent. So, our obsession with CASA should be moderated somewhat, in my view.

Refinancing turns a bad liability into a good liability under certain conditions. When short-term debt is converted into long-term debt with fixed interest rates and where the opportunities of the asset side of the balance sheet as such that the yield on the asset is far more than the cost of the money used to fund it, then the business become more profitable and less fragile (because of asset-liability mismatch is reduced). So bad liabilities can be converted into good ones.

Another source of float money is vendor financing of receivables and inventory. This happens in well-run retail operations, but back in 2011, when I was doing working on a presentation on float (), I took a look at Amazon and was astonished to find this:

Inventories: $5 billion

Accounts Receivable: $ 2.5 billion

Fixed Assets: $ 4.4 billion

Float: $15 billion

Amazon's float was so huge that it exceeded the sum of all assets in the business! So, the entire operation was funded by OPM, which is insane. I should have bought the stock when I found this, but I didn't because of insanity. 😀tinyurl.com/4cyuaczy

Inventories: $5 billion

Accounts Receivable: $ 2.5 billion

Fixed Assets: $ 4.4 billion

Float: $15 billion

Amazon's float was so huge that it exceeded the sum of all assets in the business! So, the entire operation was funded by OPM, which is insane. I should have bought the stock when I found this, but I didn't because of insanity. 😀tinyurl.com/4cyuaczy

One more thought on exit barriers. These barriers in competition can prolong a business's competitive edge. Example: Balkrishna Industries is the world's lowest-cost producer of off-road tyres. This is a labour-intensive business—hence BKT's cost advantage, which is manufactured in India.

Question: Why haven't the European companies shifted production to Asia?

Answer: Exit barriers. European labour markets are rigid, and it's very hard to shut down uncompetitive plants. Another reason why exit barriers are high is that in at least one of the large European competitors, there is a mental reluctance to close plants there and shift production to Asia because the company is owned by the local community, where generations of people have worked for the company—they would rather lose market share than move to Asia.

So, in some situations, exit barriers on bad assets of other people can make you strong. It's a pari-mutual world.

Question: Why haven't the European companies shifted production to Asia?

Answer: Exit barriers. European labour markets are rigid, and it's very hard to shut down uncompetitive plants. Another reason why exit barriers are high is that in at least one of the large European competitors, there is a mental reluctance to close plants there and shift production to Asia because the company is owned by the local community, where generations of people have worked for the company—they would rather lose market share than move to Asia.

So, in some situations, exit barriers on bad assets of other people can make you strong. It's a pari-mutual world.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh