What makes a good necktie?

I was recently served this ad on Instagram, which shows a clip of Jesse Watters saying that Otaa Brothers makes the best ties in the world.

Wow, the best ties in the world! So, I looked into it.

I was recently served this ad on Instagram, which shows a clip of Jesse Watters saying that Otaa Brothers makes the best ties in the world.

Wow, the best ties in the world! So, I looked into it.

On their Instagram page, Otaa has ads like this one below. Their marketing follows a familiar pitch: luxury brands are ripping you off and we sell the same quality for less because we're good blokes. Their ad is reminiscent of "Dollar Shave Club."

Intrigued, I bought one.

Intrigued, I bought one.

So what actually makes a tie high-quality? Lets compare

First is the fabric. A high-quality tie will be made from natural fibers, such as pure silk, wool, cashmere, linen, or cotton. These are from Shibumi Firenze (they're great). Natural materials will feel better in your hand.

First is the fabric. A high-quality tie will be made from natural fibers, such as pure silk, wool, cashmere, linen, or cotton. These are from Shibumi Firenze (they're great). Natural materials will feel better in your hand.

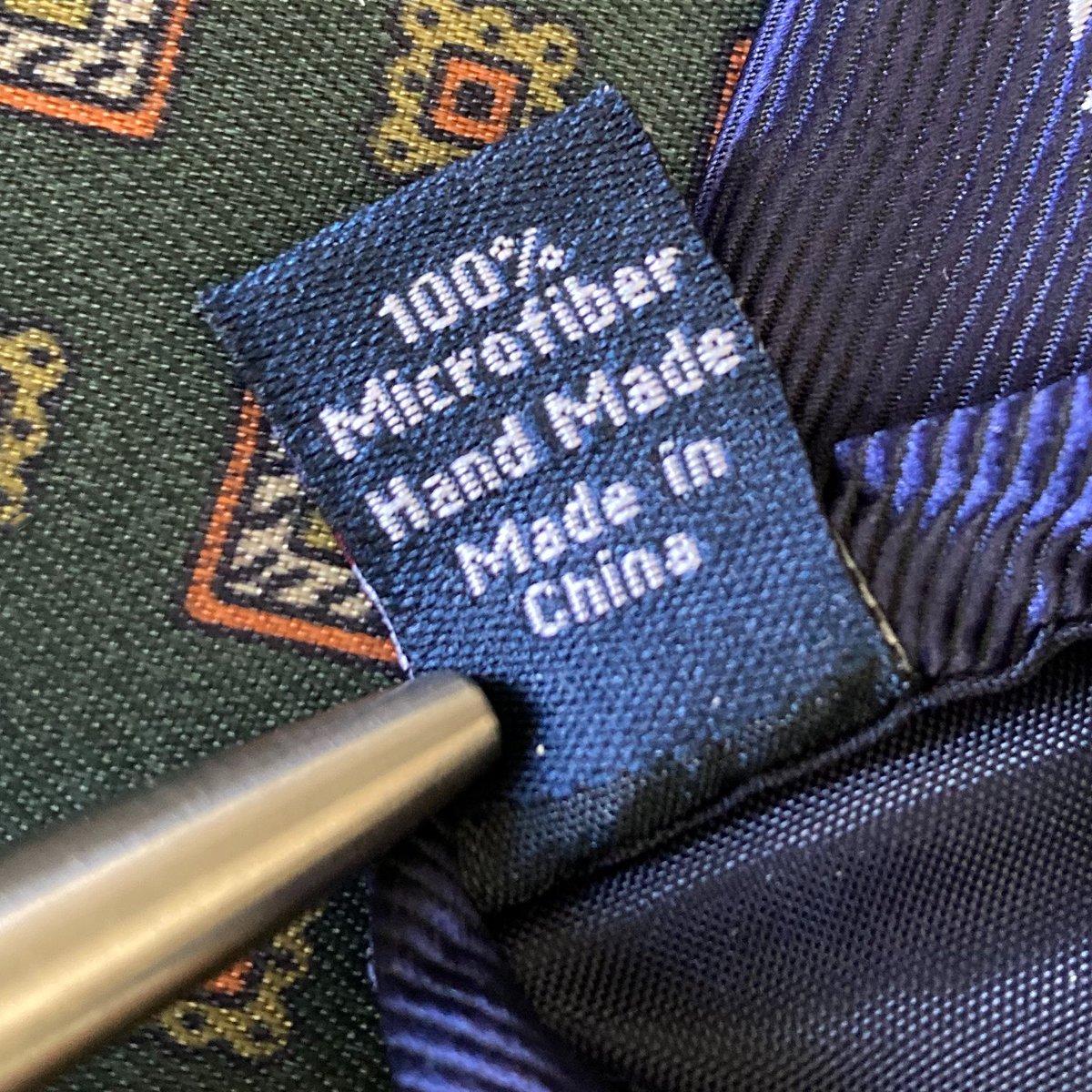

The Otaa tie I bought is made from microfiber, which is a pure synthetic (usually derived from polyester).

As an aside, the label says that it's "designed in Australia and 'handmade' in China." But it's not actually handmade. We'll get into that later.

As an aside, the label says that it's "designed in Australia and 'handmade' in China." But it's not actually handmade. We'll get into that later.

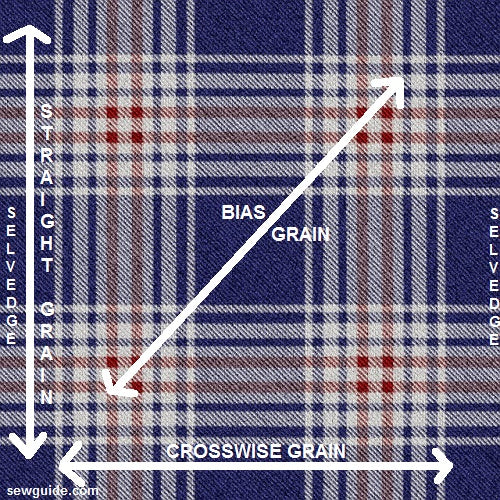

Next, we have the cut. A good tie should be cut "on the bias," which means placing the paper pattern on the fabric at a 45 degree angle. This allows the tie to drape properly. It also allows the fabric to naturally stretch, which means a more comfortable fit around your neck.

Unfortunately, this Otaa tie wasn't cut on the bias. The ribs run vertically, not diagonally. But this is typical for these types of fabrics, as the pattern has to look a certain way when worn. The EG Cappelli tie on the right (genuine high quality) also has vertical ribs.

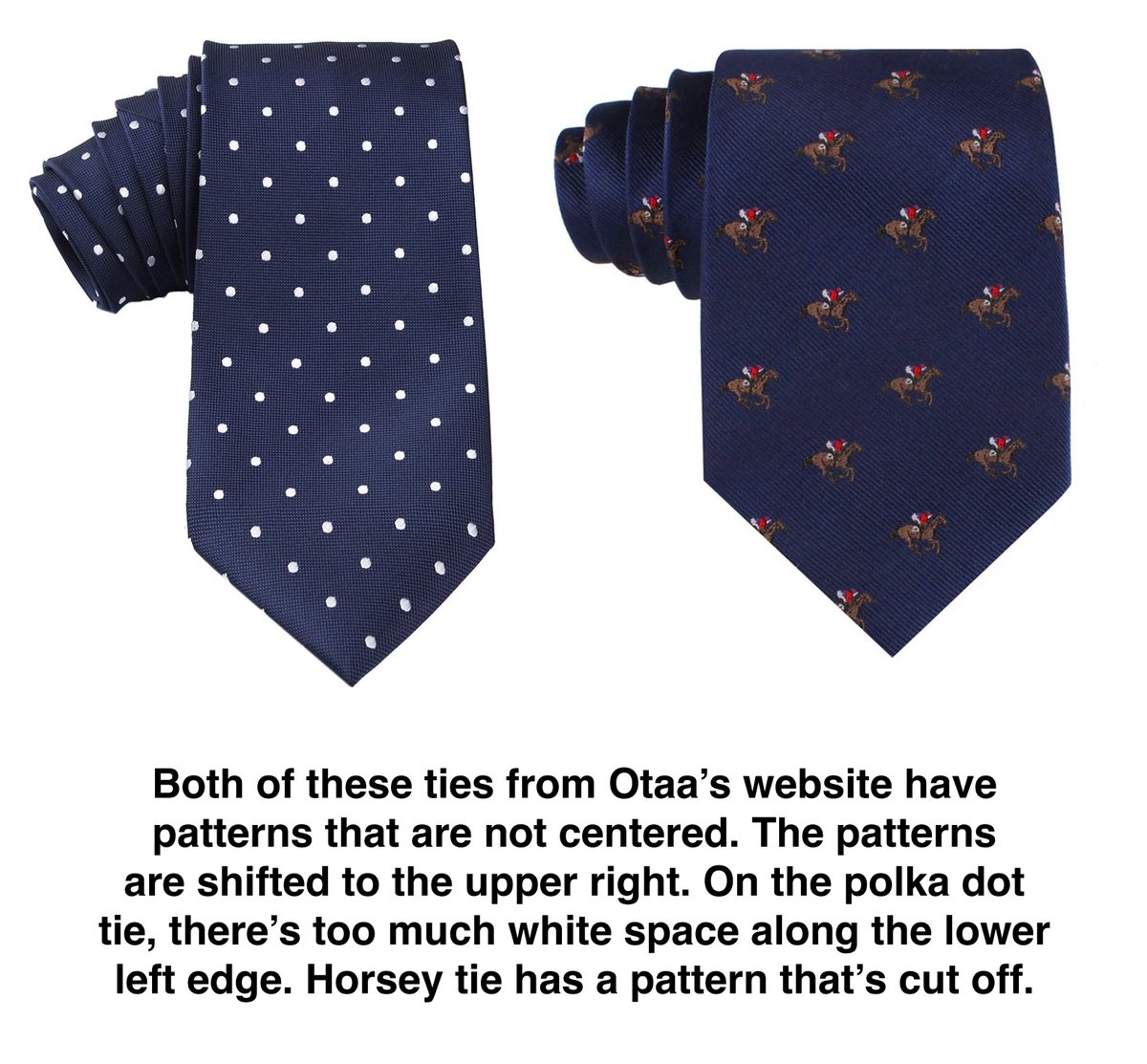

When placing the paper pattern down on the fabric, the cutter should make sure the fabric's pattern is centered. The anchor pattern on my Otaa tie is mostly centered, but many ties on their website are not. This shows poor quality control.

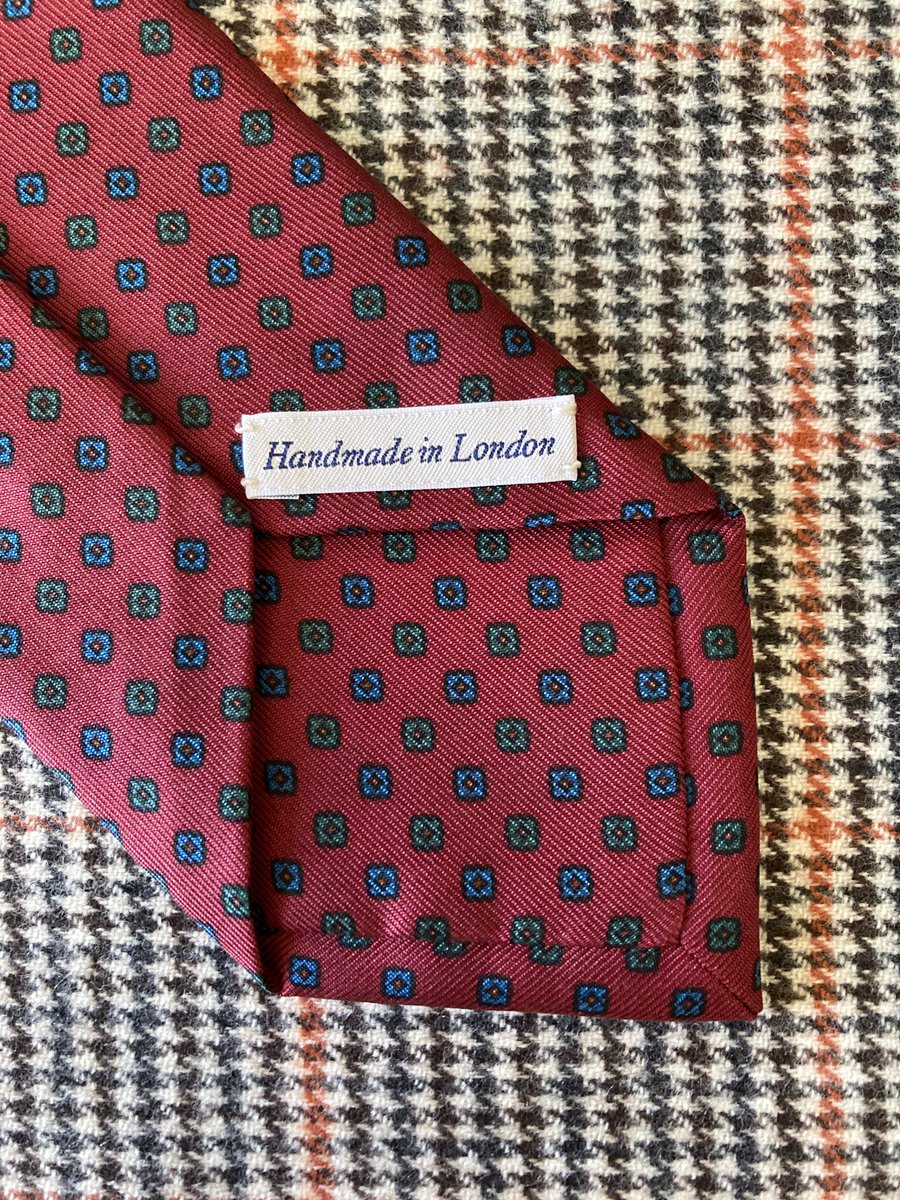

Now, let's flip the tie over. A high-quality tie should be "self tipped," which means the back of the blade is finished with the same shell fabric. This shows the maker spared no cost. Or it can be "untipped," at which point, the edges should be hand-rolled and -sewn.

This Otaa tie has been tipped with black polyester. The polyester is probably no cheaper than the microfiber (which is already cheap). However, by using black polyester, they can use the same material across their entire range, which cuts down on overall production costs.

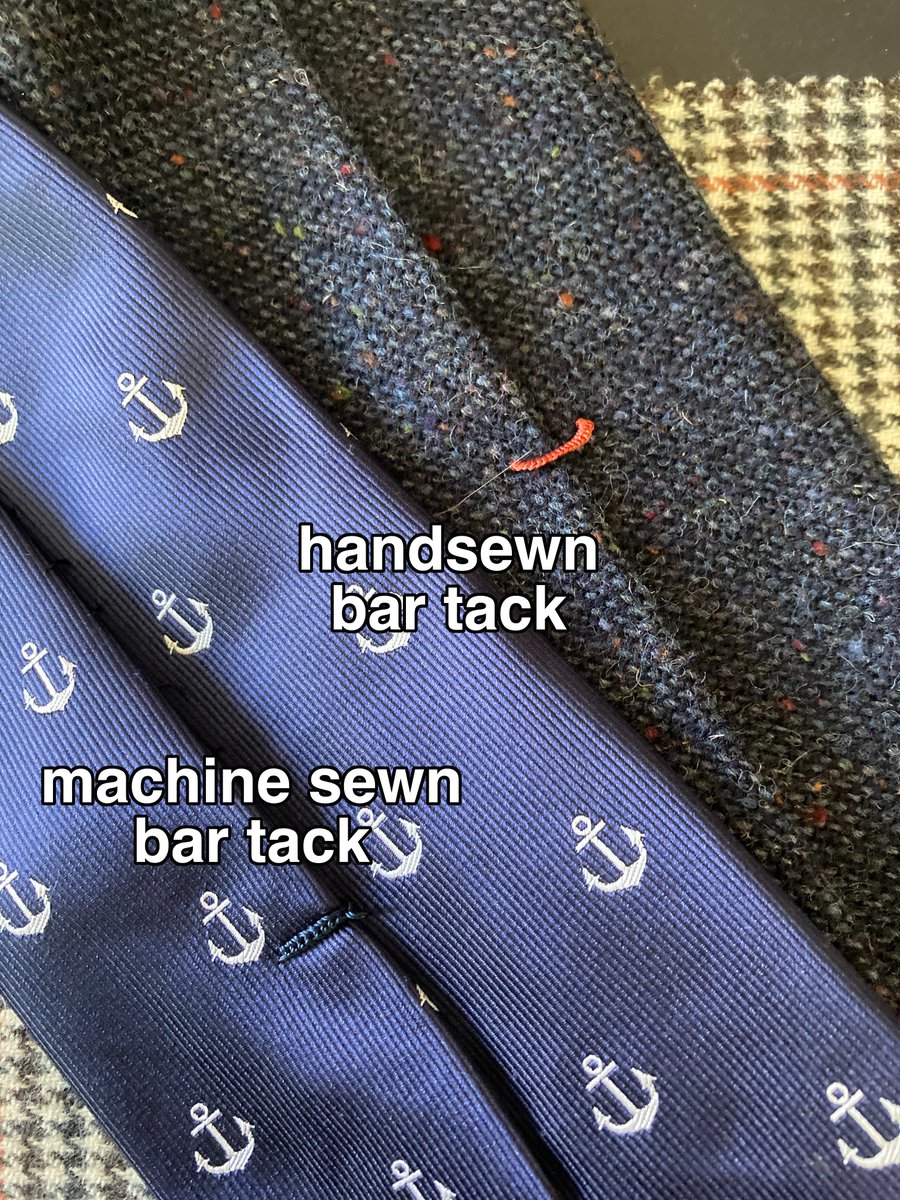

Next is the sewing. A quality tie will have a handsewn slip-stitch running up the tie's spine. The bar tacks will also be sewn by hand. This handsewn slip-stitch will have more give than a machine-made lockstitch. It also shows a bit of craftsmanship. A video is from Tom James:

By contrast, a machine-made tie will often be made on a LIBA machine. You can see how the process here is much quicker. An operator loads the material and a tie pops out of the other end. This is a deskilling of labor, so the manufacturer can also pay their workers less.

Otaa labels their ties as "handmade" but they're actually machine-made. You can tell from the evenness of the slip-stitch and the look of the bar tack. Hands are required to operate a machine, but when people read "handmade," they assume a certain level of craftsmanship.

Now let's open the tie up. Most ties are made with a construction known as a "three fold," meaning the shell fabric is folded upon itself three times. Some ultra-premium ties are made with a seven fold, which requires more fabric (and thus more cost). This drapes heavier

Of course, Otaa's tie is made with a three-fold construction. There's nothing inherently wrong with that—some people may even prefer a three-fold construction over a seven-fold. But along with everything else above, it demonstrates the maker was sensitive about costs.

Next is the interlining. If the shell fabric is not robust, like wool or a thick silk, then the tie will need something inside to give it some "body. Luxury ties typically have a wool interlining because this keeps its shape, drapes better, and sheds wrinkles more easily.

Remember, wool has more "memory" than cotton or linen, so it will more easily return to its original shape after a long day of wear. However, wool interlinings are expensive, to cut costs, manufacturers often use cheaper synthetic materials or blends.

I don't know what Otaa used for their interlinings (and can't tell without burning it; too lazy for that). But it feels slick. Does not look like the wool interlinings I've seen in higher-end ties. Here's a comparison of the Otaa next to an EG Cappelli

Finally, there's the finishing. Quality ties are gently steamed to preserve the soft roll along the tie's edge. Cheaper ties are pressed flat like a panini. You can tell the difference between the flat Otaa tie on the left and the handmade Sam Hober ties on the right.

All of these things should manifest in some way when the tie is worn. See how in the first pic, there's a nice dimple (made possible because of the quality materials). The second pic shows a soft edge (done with skilled steaming, not hard pressing).

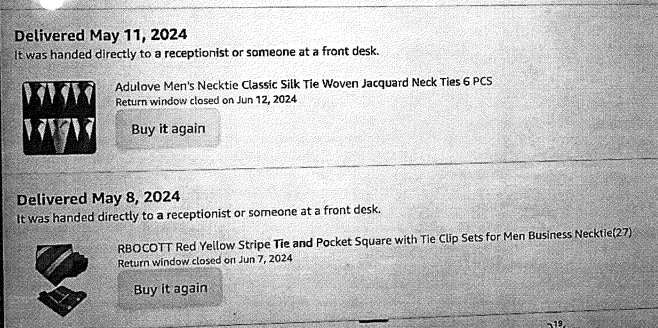

In one of their ads, Otaa compares their $50 ties to $300 luxury ties. I think it's better to compare them to $8 ties on Amazon, as these are all synthetic ties made in low-cost countries using automated machines. Rudy Giuliani was smarter to buy his ties from Amazon:

I bring this up because it bothers me when companies feed the public's cynicism on why things cost what they do. "Oh well, Otaa's ties are $50, so why is this other company charging $200? What a rip off!" But the reason has to do with materials and craftsmanship.

This sort of cynicism makes it harder for true tailors, makers, and craftspeople to make a living doing what they do. There's nothing wrong with wearing a lower-quality, machine-made tie, but companies should be honest. It's farcical to compare $50 polyester ties to Vanda:

If you want a high-quality tie, check out Sam Hober (among the best value, as they're bespoke and fully handmade for about $110). Also EG Cappelli, Drake's, Shibumi Firenze, and Vanda Fine Clothing (often made with no interlining, so they're super light and scarf-like).

Other notables include Tie Your Tie, Rampley, and Bigi Milano. For something more affordable, scour eBay for brands like Ben Silver. Finally, Chipp Neckwear makes ties in NYC. Jesse says he's concerned about the offshoring of US manufacturing jobs, so he should buy US-made ties.

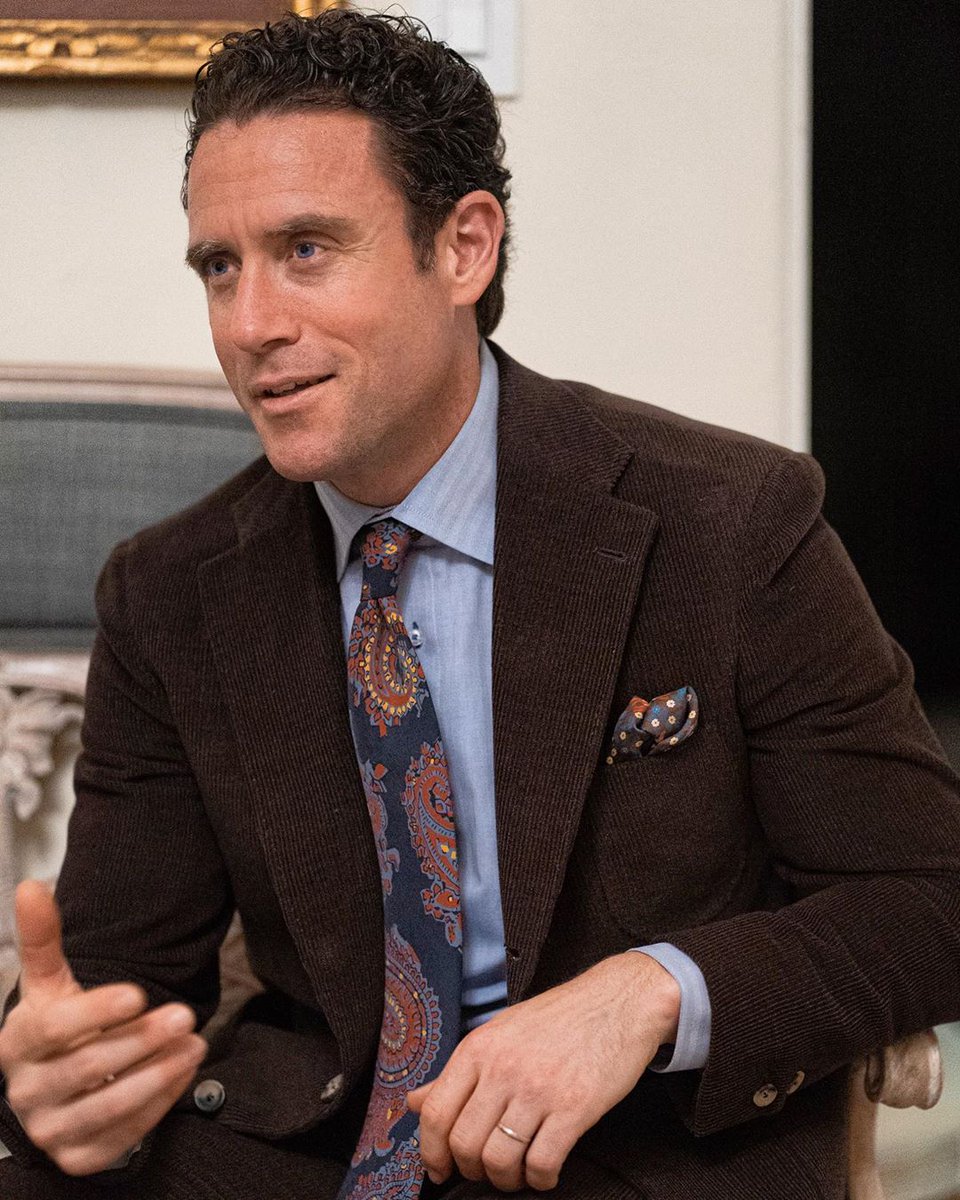

Lastly, here's Ted wearing a handmade tie from Tie Your Tie. Notice the soft roll to the edge (three-dimensional shaping), pure silk fabric (quality material), and untipped blades that have been finished with a hand-rolled, handsewn edge (true craftsmanship). What a gentleman.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh