What’s going on with lithium-ion battery prices?

In short, they’re plummeting, and the implications are just starting to ripple out across the automotive and power sectors.

A short thread:

In short, they’re plummeting, and the implications are just starting to ripple out across the automotive and power sectors.

A short thread:

Prices for lithium iron phosphate (LFP) battery cells in in China fell 51% over the last year and now sit at $54/kWh. The average global price for these cells last year was $95/kWh.

Drivers: Falling raw material prices.

Cathode share of total cost of a battery cell have fallen from over 50% at the beginning of 2023 to below 30% today.

Cathode share of total cost of a battery cell have fallen from over 50% at the beginning of 2023 to below 30% today.

Drivers: Overcapacity.

There is way more battery capacity than is currently needed, and more is coming. Utilization rates are falling and manufacturers are cutting prices to maintain market share.

Margins are being compressed.

There is way more battery capacity than is currently needed, and more is coming. Utilization rates are falling and manufacturers are cutting prices to maintain market share.

Margins are being compressed.

Technology and manufacturing improvements are also still playing a big role. China’s battery giants continue to invest heavily in automation and R&D and are launching new products at a frenetic pace.

Battery cells at $50/kWh means the technology to decarbonize most of road transport globally is already here. Pack prices in China for LFP batteries are now at $75/kWh.

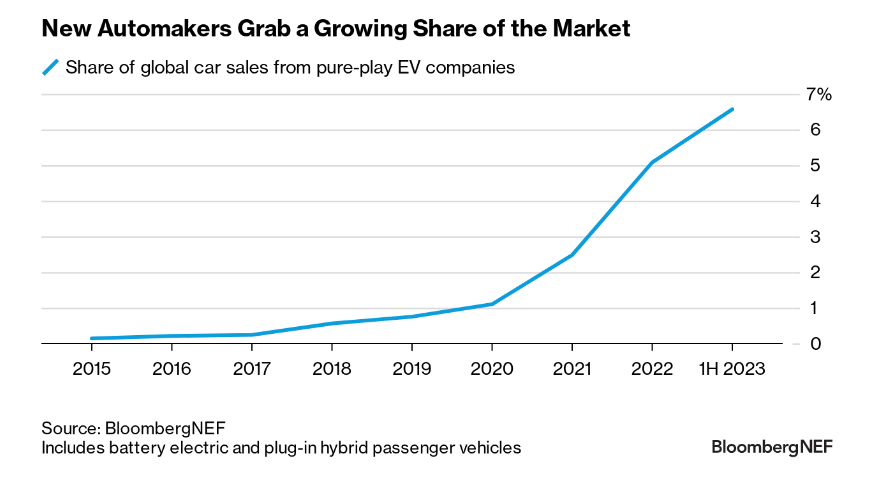

China is the world’s largest auto market, and battery-electric vehicles are currently the cheapest drivetrain by average transaction price in the country, even after stripping out mini city cars from the dataset.

Another way to look at it: Almost two-thirds of EVs available in China are already cheaper than internal combustion engine models. Still, intense price competition going on and it’s not clear how long everyone can hold on.

The stationary energy-storage market may be the biggest beneficiary.

Overcapacity isn’t going anywhere anytime soon, but BNEF expects global stationary storage installations to rise to 67GW/155 GWh this year, up 61% from last year.

Overcapacity isn’t going anywhere anytime soon, but BNEF expects global stationary storage installations to rise to 67GW/155 GWh this year, up 61% from last year.

Over the last four years, there was a steady drumbeat of predictions that batteries and battery metals would be in short supply indefinitely.

That's not what's happened, at least not yet.

That's not what's happened, at least not yet.

That's it for now. For more, see my latest column for @BloombergNEF and @business

bloomberg.com/news/newslette…

bloomberg.com/news/newslette…

This weeks piece features analysis from my brilliant colleagues @AndyLeachBatt, Jiayan Shi, @EvelinaStoikou, Nelson Nsitem and @YayoiSekine

Follow them if you don't already!

Follow them if you don't already!

@AndyLeachBatt @EvelinaStoikou @YayoiSekine You can sign up for the Bloomberg Hyperdrive Newsletter here:

Daily briefings from around the world, expertly edited by @crtrud with weekly contributions from BNEF analysts.bloomberg.com/account/newsle…

Daily briefings from around the world, expertly edited by @crtrud with weekly contributions from BNEF analysts.bloomberg.com/account/newsle…

Some more thoughts on the battery overcapacity situation and what it means globally here:

bloomberg.com/news/newslette…

bloomberg.com/news/newslette…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh