The 1918 flu is called the "Spanish flu" because in most places, the media censored it. Except Spain, where they reported honestly. This isn't a conspiracy theory - it's a historical fact. And I think it is occurring right now again with COVID:

This article in The New Republic - "How America’s Newspapers Covered Up a Pandemic" - provides an overview of what happened in 1918. In short, the media either avoided talking about the flu altogether, or they blamed something else for the damage the flu was causing.

"the big-city newspapers...sugarcoated the truth, practicing an alarming level of self-censorship. Any article or headline suggesting more than casual concern about the disease would be open to attack"

"Only by putting together the tiny headlines on page 11 of the Boston Post could a dutiful newspaper reader get a sense of the full extent of the epidemic"

Is this happening again right now with COVID? I think for the first few years of the pandemic, most of the press covered it honestly (indeed, some articles at the time noted the contrast between the media's early coverage of COVID and the censorship of 1918)

But as time has passed, there's been a shift towards censorship. Articles that should obviously mention COVID now rarely do. In some cases, this is debatable, like a story on student absences. But for coverage of health trends, this is inexcusable. A few recent examples:

This article from Today reports on an alarming trend: the growing number of young, seemingly healthy people, having unexplained heart attacks. The writer suggests the cause could be obesity, or marijuana use, but does not mention COVID.

This is a glaring omission, as COVID infections increase your risk of having a heart attack, and studies have found that this risk is most pronounced among young adults.

This article tackles a similar topic, although this time it's strokes rather than heart attacks. Once again, coverage on the growing number of young people having a stroke. And once again obesity is blamed, along with stress and pollution, while COVID is never mentioned.

Again, a glaring omission: getting infected with COVID significantly increases your risk of having a stroke. One study found that the odds of having a stroke increased by 52% in the year following a COVID infection.

This article is a bit different. It isn't really about a trend, but more of a sort of thinkpiece on the relationship between chronic illnesses and stress: how stress can drive them, and how doctors can ignore them.

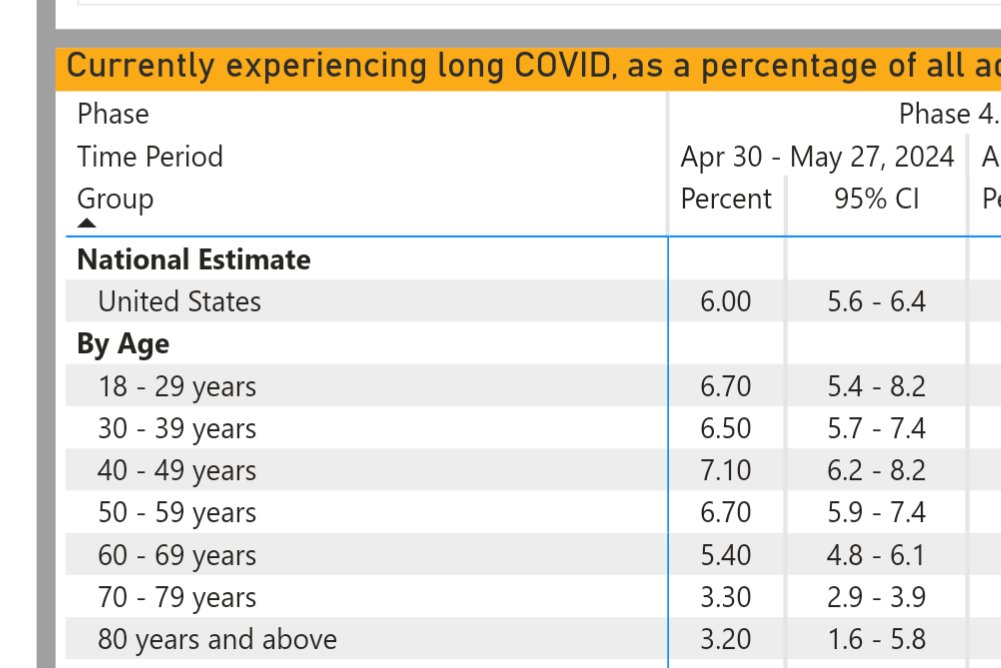

The article doesn't mention COVID. Chronic illnesses are obviously not new, and the space is much bigger than COVID, but it's odd to write a piece about chronic illness and not mention COVID given that it has been an enormous driver of chronic illness in recent years. According to the CDC, about 6% of all American adults are currently living with long COVID.

Recently, a sort of genre of article has emerged: stories about people having odd, unexplained health issues. Many of these health issues are immediately recognizable to anyone who has experienced long COVID, and yet, the articles themselves don't mention it, even as a possibility

This one tackles the number of people developing an odd persistent cough that lasts for weeks or months. The article mentions COVID only to assure the reader that COVID is certainly not the cause, then suggests the culprit might be social distancing, masks, or anxiety

But not only do COVID infections themselves frequently result in a cough during the acute stage, but a chronic cough is also one of the more common long COVID symptoms, lasting for at least a year after infection.

In this one, the writers visit a rural Texas town where many of the people living there have developed odd, seemingly unexplainable, health issues: blood clots, hearing loss, headaches, hair loss, and autoimmune disease, among other issues. The story clearly tries to place the blame on a BTC mine.

And while that may be the case, every symptom mentioned in the article is also a common long COVID symptom. What makes this more compelling is that long COVID disproportionately affects rural populations

As you read articles about declining health in the population - unexplained illnesses, the growing number of sick people - look to see if COVID is mentioned as a driver. If it isn't, take whatever symptoms the article is talking about, and look to see if there is research linking those symptoms to COVID or long COVID. More often than not, you'll probably find out that's the case.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh