Mongolia's Olympic uniforms are lovely. But what's up with the wording on this tweet? Is the insinuation that we don't do the same? Let's talk about how the USA Olympics uniform connects to our heritage, culture, and history. 🧵

https://twitter.com/GigaBasedDad/status/1813249423323111828

Note, while there are women on the US Olympics team, I will be talking about this from the perspective of menswear because that's what I know.

First, let's review the main elements of the uniform: an unusually trimmed navy jacket, some blue jeans, and a pair of white shoes.

First, let's review the main elements of the uniform: an unusually trimmed navy jacket, some blue jeans, and a pair of white shoes.

To understand the language of classic American dress (again, from a menswear perspective), you have to go back to 1818 when Henry Sands Brooks opened a clothing store on the corner of Catherine and Cherry streets in Manhattan. This store would revolutionize American dress.

If dress is a language then Brooks Brothers gave us our ABCs. They invented the first ready-made suit in 1849 and, by the turn of the century, debuted a soft-shouldered, dartless form of tailoring they called the "sack suit."

The sack suit carried American men from the hopping jazz clubs of the Roaring 20s through the Great Depression and onto the Ivy League campuses of a booming post-war America. It was *the* American silhouette.

It's distinguishing marks—soft shoulder line, dartless front, hook vent, and machine-finished edges—differed from European tailoring, which tended to be stiffer or more shaped. American style had a "natural" silhouette

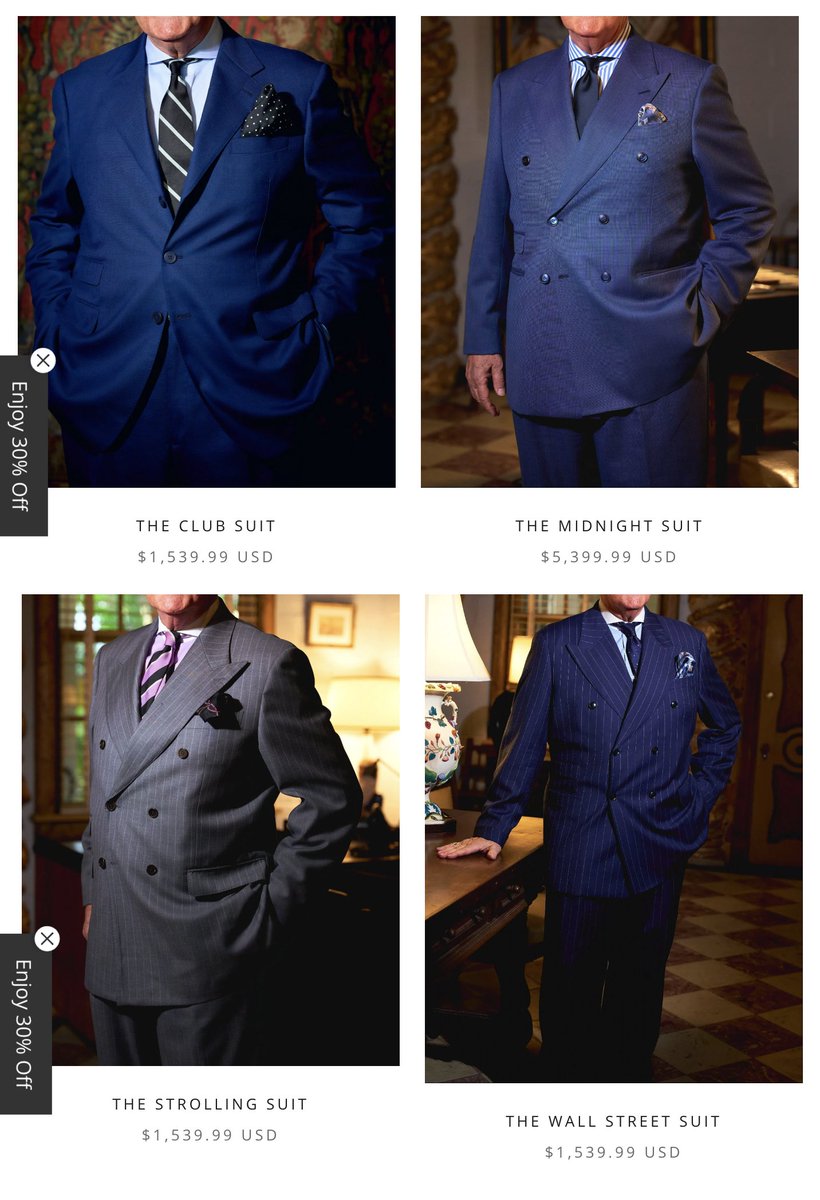

Left: American

Right: British Savile Row

Left: American

Right: British Savile Row

The main thing to understand is that, for the first half of the 20th century, what landed on the shelves at Brooks Brothers' stores often became the pillars of classic American style: the sack suit, oxford button-down, penny and tassel loafer, polo coat, Shetland sweater, etc.

This is because Brooks Brothers primarily dressed that upwardly mobile class of Americans who saw their fortunes rise with industrial capitalism. This style would later be known as "Ivy Style" because of how it defined campus dress at elite Ivy colleges. Others would copy.

These campuses put their own thumbprint on American traditions. For example, "drinking jackets" were worn in eating clubs to protect students from airborne beer. This is a 1920s Brooks Brothers jacket that Princeton students decorated with stencils (see flying beer mug).

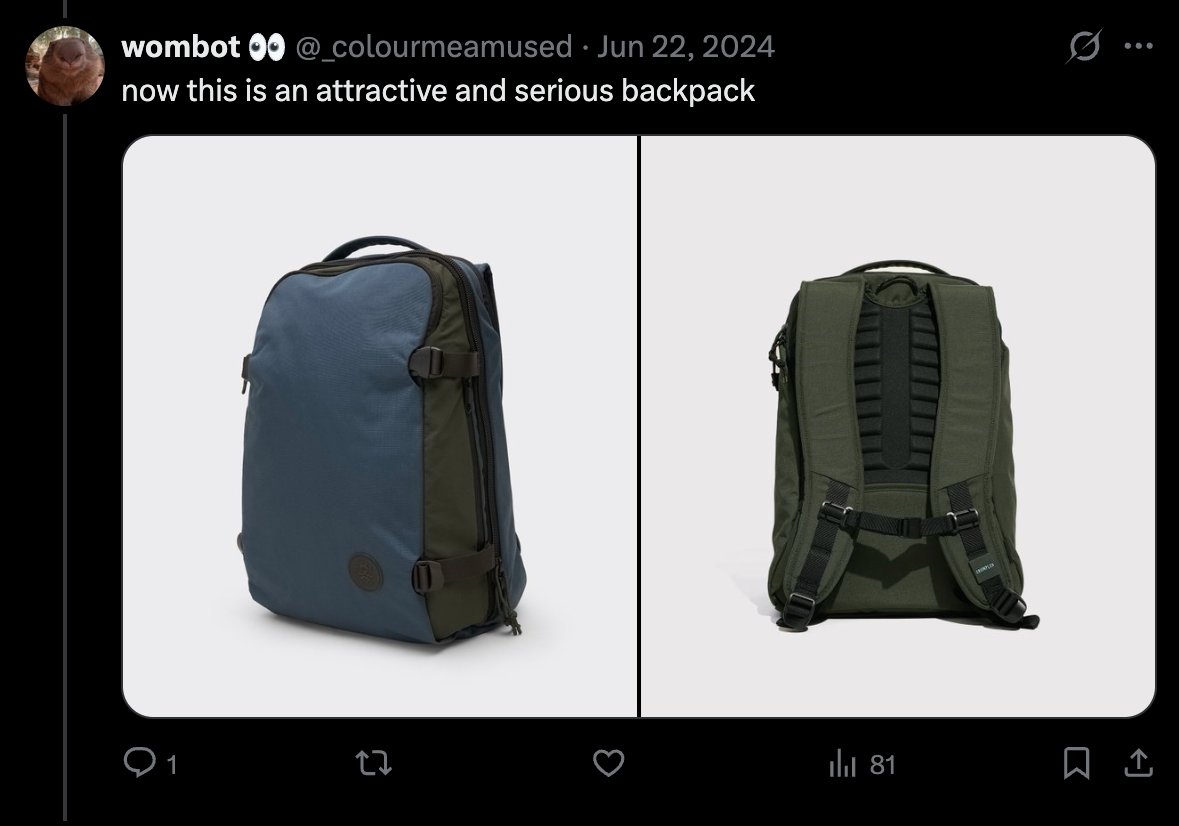

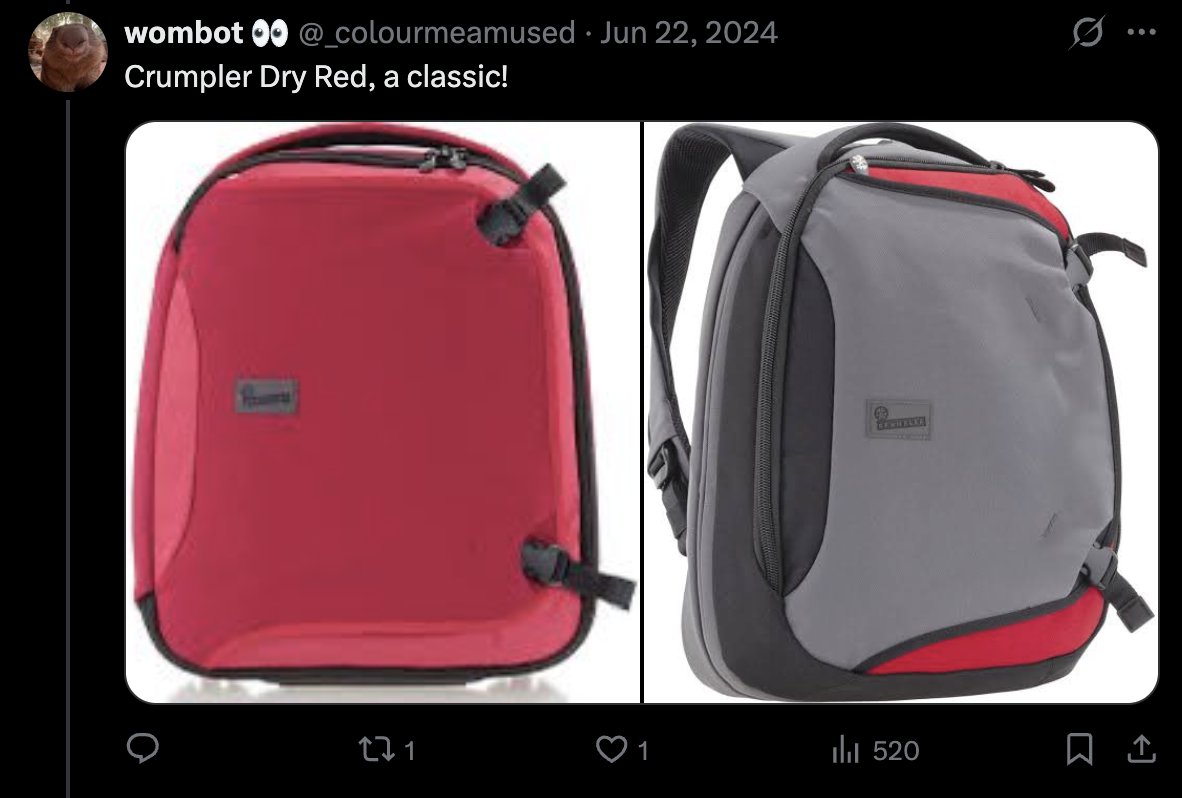

The other important university jacket is the rowing blazer (aka boating blazer). These were worn by members of rowing clubs with the unusual stripes denoting the team's colors. Since traditional American dress largely derives from the UK, we first see these in England

Here are the American versions. Yale is on the left, Harvard is on the right. Colors and stripes differ, depending on the team.

Sometimes these jackets would be emblazoned with some motif. Sometimes the stripes would take up the whole jacket, not just a trim along the edges. Buttons could be brass, mother-of-pearl, or cloth-covered. Lots of variation, but they're all distinctive

And what do we see on the US Olympics team uniform? A club blazer traditionally worn for sport. The trim is striped with our national flag colors (our club). A patch on the right side shows this is for the Olympics team (and yes, I could do without the pony, but oh well)

My one quibble is that, if they really wanted to stick to American traditions, these jackets should have been made without a front dart, which is the faint line that I've highlighted in red. But doing so would have given the jackets less shape. A design decision.

Whereas tailoring represents the history of America's upwardly mobile class, blue jeans represents the laborers. Just when Brooks Brothers invented the first ready-made suit, a Bavarian immigrant named Levi Strauss opened a dry goods store in San Francisco (1853)

Strauss made durable five-pocket pants from blue denim and copper rivets for the miners trying to strike a fortune during California's Gold Rush. This was the birth of blue jeans—what would later come to symbolize a certain kind of working-class romanticism.

The merging of the navy club blazer with blue jeans is totally natural, not just in terms of showing the two sides of American history, but also because Americans have always sought to dress things down. The American spirit is less formal than our European counterparts

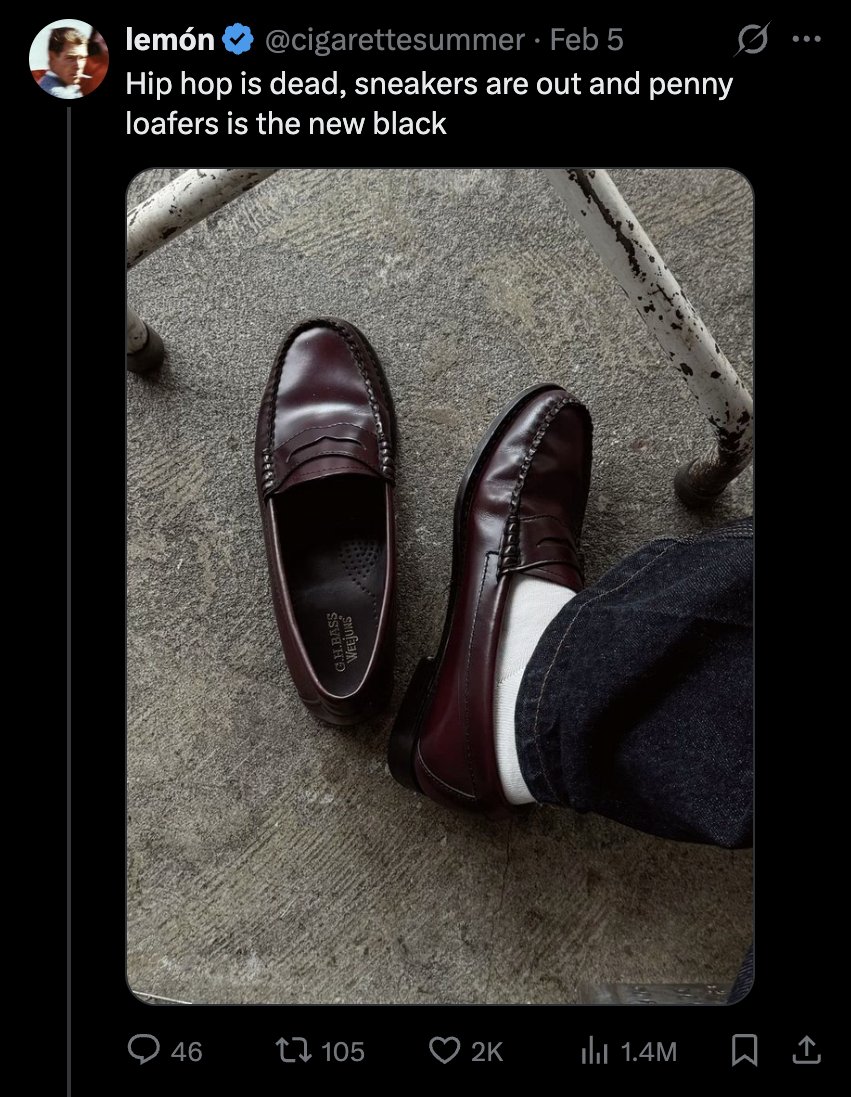

After all, we popularized the lounge suit for boardrooms; two-piece suit for day wear; the oxford button-down; patchwork madras and seersucker; penny loafers and tassel loafers with tailoring, etc. So totally natural for Olympics team to wear blue jeans with a club blazer

This casual spirit is nicely carried through in their use of a knit tie—the most casual form of traditional neckwear.

Finally, we get to the white shoes, which are called white bucks because they were historically made from buckskin (nowadays more commonly made from calf suede). Like with the club blazer, this derives from elite campus dress common in the early to mid-20th century.

Have you heard the term "white-shoe firm?" This derives from the fact that prestigious professional service firms, particularly those in banking and law, used to be primarily staffed by people who graduated from elite Ivy League colleges (and thus wore white bucks)

I don't know anything about the history of Mongolia dress. The history I just laid out for American dress starts in 1818. Perhaps Giga Based Dad wants us to go back before the 1800s and have our athletes arrive at the Olympics dressed in silk stockings, buckled shoes, and wigs.

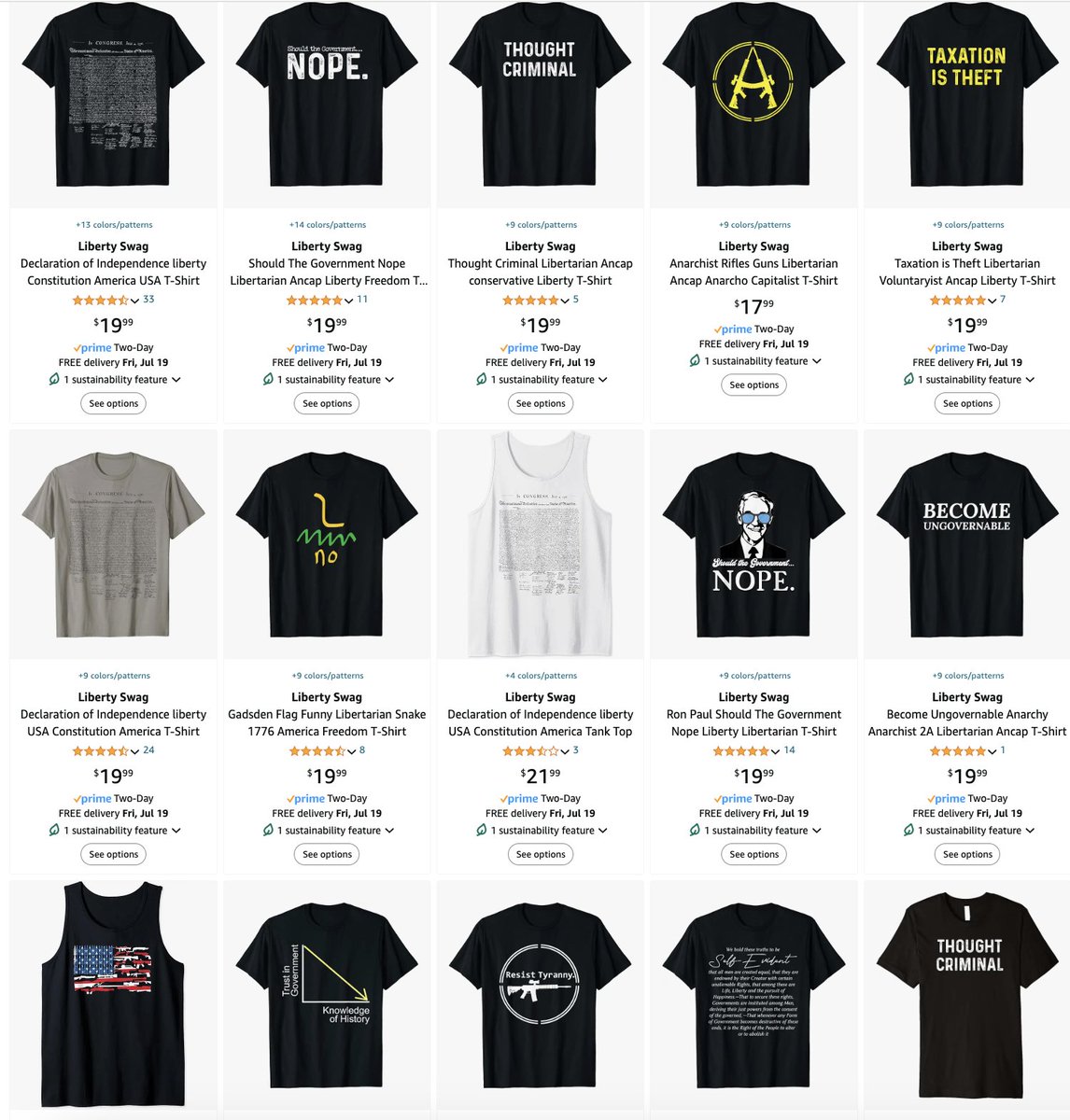

But I think our uniform does meaningfully connect us to our heritage, culture, and history, so long as you know a bit about that history. At the very least, it connects us more to our history than the $20 graphic t-shirts that Giga Based Dad is flogging on Amazon

IMO, there are a lot of accounts on here that performatively worship tradition but know very little about tradition. The comments are less about traditions and more about how they hate certain things. Many also don't practice what they preach.

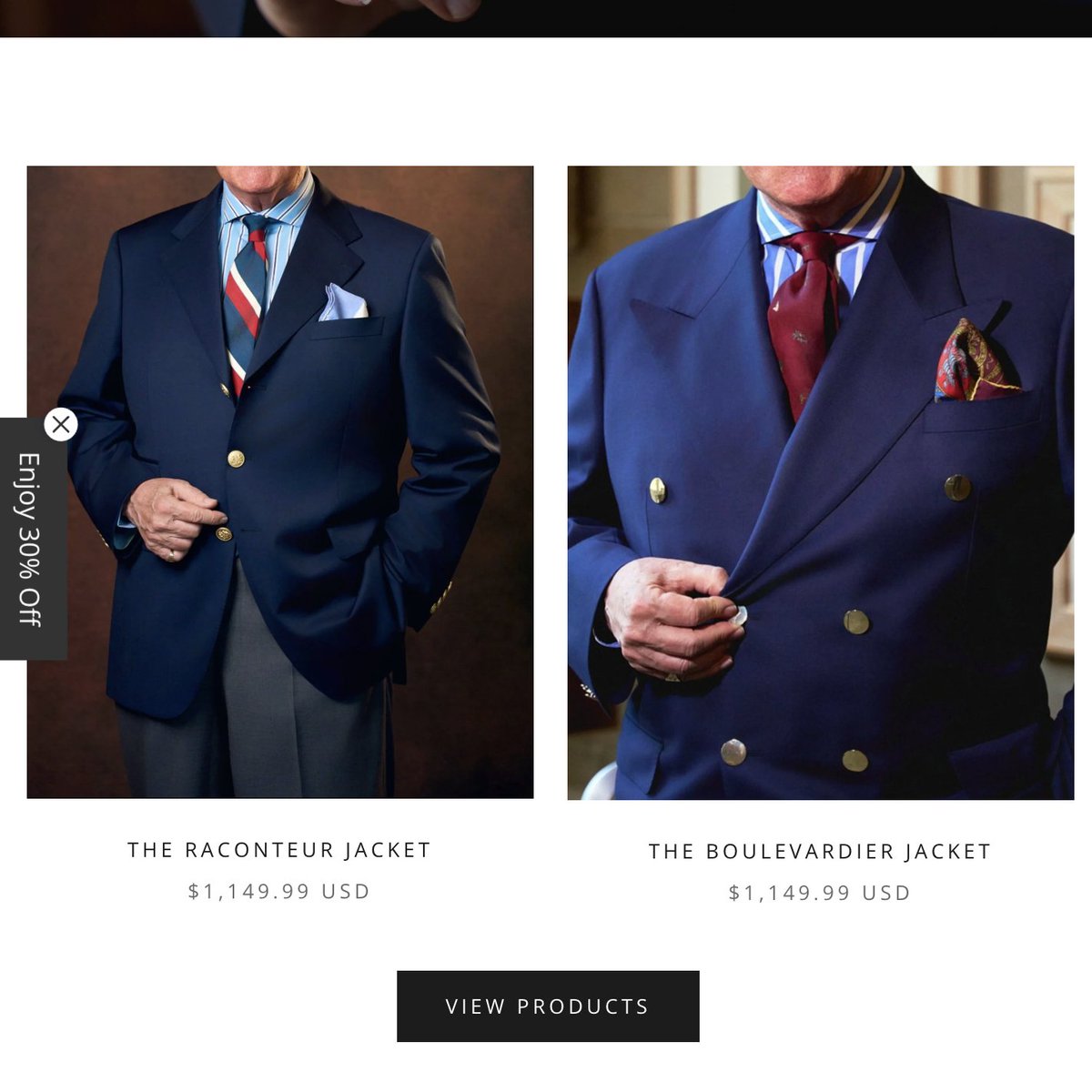

Anyway, here's a photo of how Brooks Brothers used to sell clothes. Clothes were organized by sizes and stacked in big piles with the lining out. This changed in 1966, although if you visit the most traditional of traditional American clothiers, some still do things this way.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh