KP.3, w/the unusual Q493E mutation, now dominant globally. To me, it's the first major spike change—involving real structural/epistatic change as opposed to treadmilling, stepwise antibody-evasion mutations merely keeping pace w/population immunity—since JN.1 emerged. 1/23

https://twitter.com/siamosolocani/status/1813483639306346530

Most spike mutations affect ACE2 binding similarly in BA.2, XBB.1.5, & JN.1—e.g., Y453F confers a large incr in ACE2 affinity in all—so the XBB.1.5 deep mutational scanning info from @bdadonaite & @jbloom_lab is still invaluable. But Q493E is different. 2/

https://x.com/jbloom_lab/status/1791652758141141238

In both XBB.1.5 and BA.2 spike backgrounds, Q493E imposes a devastating hit to ACE2 affinity—so large that no variant with it could survive & circulate.

Data below from:

Bloom Lab XBB.1.5 DMS -

BA.2 RBD heat map - 3/ dms-vep.org/SARS-CoV-2_XBB…

jbloomlab.github.io/SARS-CoV-2-RBD…

Data below from:

Bloom Lab XBB.1.5 DMS -

BA.2 RBD heat map - 3/ dms-vep.org/SARS-CoV-2_XBB…

jbloomlab.github.io/SARS-CoV-2-RBD…

Initially, the bare fact that Q493E existed in JN.1* indicated something more was happening.

Later, @yunlong_cao showed that on a JN.1+F456L background Q493E actually *increases* ACE2 binding & efficiently evades Class 1 Abs—the rare win-win mutation. 4/

Later, @yunlong_cao showed that on a JN.1+F456L background Q493E actually *increases* ACE2 binding & efficiently evades Class 1 Abs—the rare win-win mutation. 4/

https://x.com/yunlong_cao/status/1798091739418509476

I don't think it's known for certain why Q493E has such dramatically different effects on ACE2 affinity and antibody evasion in JN.1 + F456L compared to BA.2 and XBB.1.5, but it's clear some sort of epistasis with JN.1-specific mutations is at work. 5/

So far the only major advance on baseline KP.3 is S:∆S31, a deletion found in KP.3.1.1 (& ~all other growing JN.1* lineages) that adds a glycan (sugar) to N29, increasing Ab evasion.

∆S31 provides a surprisingly potent advantage, as @BenjMurrell's growth chart illustrates. 6/

∆S31 provides a surprisingly potent advantage, as @BenjMurrell's growth chart illustrates. 6/

KP.3's higher ACE2 affinity means it has more "space" to maneuver, i.e. a greater variety of stepwise, Ab-evading spike RBD mutations available. None have yet appeared, but you can be sure they will in the coming months—F456L, now universal, took time to emerge & grow. 7/

There is other evidence Q493E marks a significant departure from all previous JN.1 lineages.

R346T & F456L together give "FLiRT" variants their name. KP.3 is often called a "FLiRT" variant, but it is NOT: it lacks R346T, which is in >90% of non-KP.3 sequences. 8/

R346T & F456L together give "FLiRT" variants their name. KP.3 is often called a "FLiRT" variant, but it is NOT: it lacks R346T, which is in >90% of non-KP.3 sequences. 8/

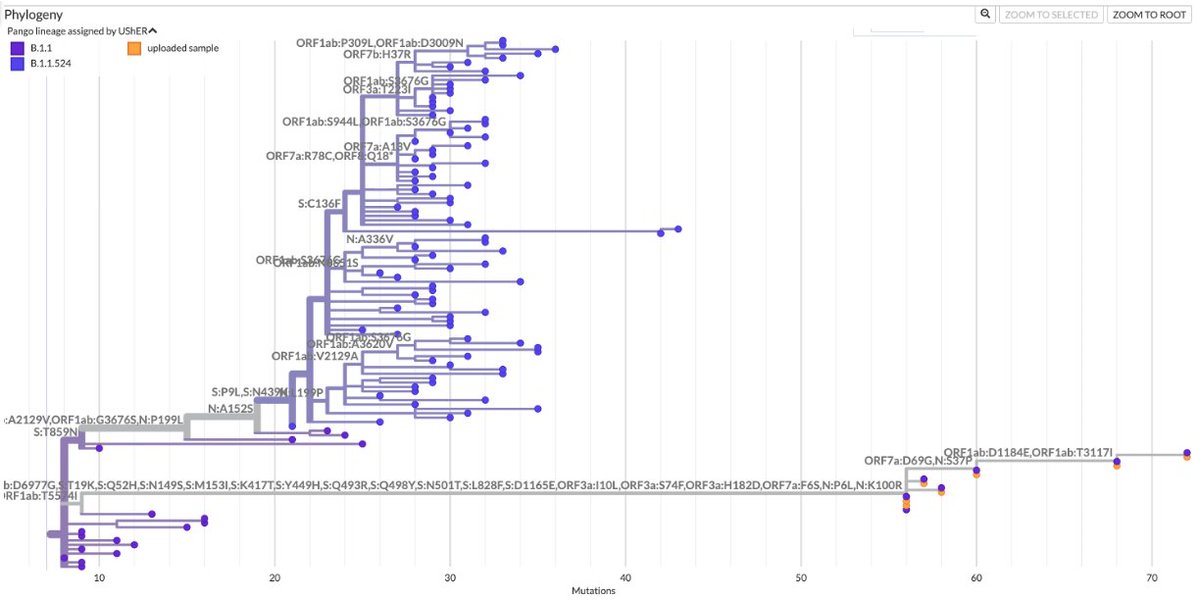

With the exception of a few scattered singlets & one 8-seq branch (which also has S:H445R), R346T is entirely absent from KP.3.

Though not absolutely incompatible, it's clear R346T does not work in KP.3, in stark contrast to all other JN.1 lineages. 9/

Though not absolutely incompatible, it's clear R346T does not work in KP.3, in stark contrast to all other JN.1 lineages. 9/

In some ways, this is a return to normal: JN.1 has N450D, & R346T has always been incompatible with N450D, the only exceptions being small lineages of dying variants—mainly FV.1 (a BA.2.3.20 descendant) and JG.3.2.1 (an EG.5.1 descendant). 10/

It's unclear why R346T & N450D don't mix well, but could Q493E's incompatibility w/R346T provide a clue?

346, 450, & 493 are very near each other.

R346T, N450D, & Q493E all involve increased negative electric charge.

(see up + down RBD in BA.2.86 spike below, PBD 8XLV)

11/

346, 450, & 493 are very near each other.

R346T, N450D, & Q493E all involve increased negative electric charge.

(see up + down RBD in BA.2.86 spike below, PBD 8XLV)

11/

But just as R346T is incompatible with KP.3, I expect some mutations incompatible with FLiRT lineages may be compatible with KP.3, though no major ones have emerged yet.

12/

12/

Clearly Q493E is hugely beneficial for the virus. Why, then, has it not emerged in other JN.1* variants?

Incompatibility with R346T is only a partial explanation; until very recently, a huge number of non-R346T lineages existed. None acquired Q493E.

Why not? 13/

Incompatibility with R346T is only a partial explanation; until very recently, a huge number of non-R346T lineages existed. None acquired Q493E.

Why not? 13/

Some highly advantageous mutations never appear simply because they're extremely hard to acquire—esp those requiring 2 or 3 nuc mutations. 2-nuc mutations are extraordinarily rare & usually only emerge amid intense selection pressure. E.g. F486P 14/

https://x.com/LongDesertTrain/status/1556473625456377863

Q493E only requires 1 nuc mutation. But some nuc muts are far more common than others.

@richardneher & @jbloom_lab showed this in contexts where AA selection does not operate (b/c no mutation can cause an AA change—i.e. all mutations are synonymous). /15

jbloomlab.github.io/SARS2-mut-spec…

@richardneher & @jbloom_lab showed this in contexts where AA selection does not operate (b/c no mutation can cause an AA change—i.e. all mutations are synonymous). /15

jbloomlab.github.io/SARS2-mut-spec…

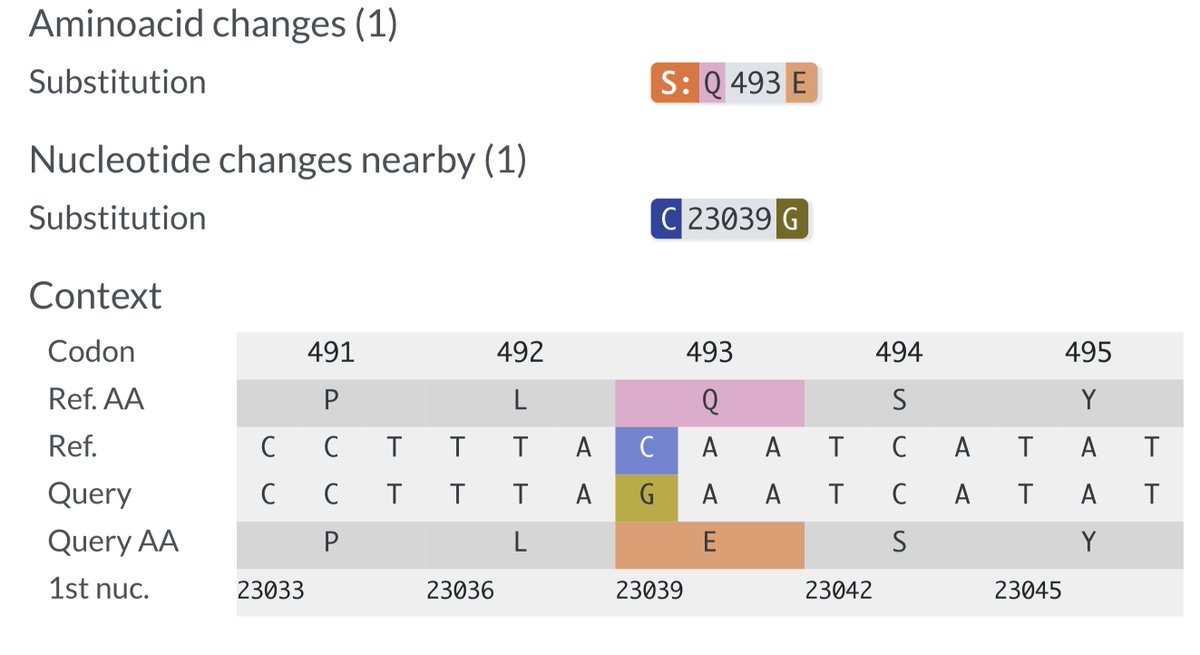

Q493E requires a C->G nucleotide mutation, which is the rarest of all—about 40x less common than C->T mutations in the contexts Neher & Bloom analyzed. /16

In >3400 highly mutated, chronic-infection seqs, I found similar results: compared to C->T, overall C->G mutation rate was 40.2-fold lower.

• Synonymous C->G rate 374-fold lower (unadjusted for contexts)

• Non-synonymous C->G rate 26.4-fold lower (unadjusted)

/17

• Synonymous C->G rate 374-fold lower (unadjusted for contexts)

• Non-synonymous C->G rate 26.4-fold lower (unadjusted)

/17

(Aside: I'm running something to calculate the rates of each nuc mutation in all 16 nuc contexts for each specific sequence, but it might take 2 weeks to complete. Been running 40 hours so far. Some vestige of its beginning remains, but no prospect of an end in sight.)

There's been much discussion of the convergent mutations we often see, i.e. the same mutations occurring independently in numerous lineages—R346T and F456L among the most notable.

@dfocosi regularly updates a diagram illustrating this convergence. /18

@dfocosi regularly updates a diagram illustrating this convergence. /18

https://x.com/dfocosi/status/1807054825978290298

.@siamosolocani & I recently tried to list convergent C->G mutations. We couldn't think of any. I don't think any exist. So it's not surprising no other JN.1 lineage has gotten Q493E.

(The few non-KP.3 Q493E seqs are IMO all isolated singlets or contamination/recombination) /19

(The few non-KP.3 Q493E seqs are IMO all isolated singlets or contamination/recombination) /19

(There is 1 fascinating, maddening, enigmatic C->G mutation that's convergent in the longest, most extreme chronic-infection seqs & @solidevidence's Cryptics. The total lack of other convergent C->G mutations only magnifies its inscrutable allure. Another day, another 🧵) /20

Finally, Q493E may open one other door that's been closed until now. The BA.2 Bloom Lab RBD heat map showed two viable Q493 mutations towered above the rest in ACE2 affinity: Q493A & Q493V.

These have been off-limits (except in a few chronic-infection sequences)... /21

These have been off-limits (except in a few chronic-infection sequences)... /21

...because each required two rare nuc mutations: the ultra-rare C->G together with an A->C or A->T mutation, both of which are also uncommon. In the case of Q493A, the mutations must occur in the correct order as well since Q493P is not viable. /22

493A & 493V may not confer the same huge increase in ACE2 affinity on a KP.3 background as on a BA.2 background, & they could ruin KP.3 stability or antibody evasion.

But the 2nd Q493A seq ever just appeared—the other was in Oct 2022—so this may be one to watch for. 23/end

But the 2nd Q493A seq ever just appeared—the other was in Oct 2022—so this may be one to watch for. 23/end

Screwed up this picture. The bottom caption should NOT have R346T.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh