Why did past societies build so much "useless" beauty everywhere — and why did we stop?

It might be a measure of a culture's health... (thread) 🧵

It might be a measure of a culture's health... (thread) 🧵

Street lights are seen by everyone. But what about things hardly seen at all, like fittings on the sides of doors?

This was the kind of thing Victorian society cared about — but why?

This was the kind of thing Victorian society cared about — but why?

The mantra of the 20th century was to say that ornamentation has no purpose, so get rid of it.

But ornaments assign ordinary things meaning. They speak to the tradition or craft that produced it...

But ornaments assign ordinary things meaning. They speak to the tradition or craft that produced it...

It might be something symbolic. In Mediterranean culture, the acanthus leaf means enduring life — so it was embedded right into columns.

Small details like this connect you to the past (several millennia in this case).

Small details like this connect you to the past (several millennia in this case).

Even something as mundane as street furniture can do this. London's curious "sphinx benches" were a nod to the arrival of Cleopatra's Needle from Egypt in 1878.

The modern, minimalist bench tells no such story.

The modern, minimalist bench tells no such story.

What about cost?

The Minimalists preached that building as cheaply as possible is virtuous. As Adolf Loos said: "The evolution of culture marches with the elimination of ornament from useful objects."

But what's fundamentally missing here?

The Minimalists preached that building as cheaply as possible is virtuous. As Adolf Loos said: "The evolution of culture marches with the elimination of ornament from useful objects."

But what's fundamentally missing here?

John Ruskin's first principle of architecture has the answer: sacrifice.

Things should be costly (either in materials or the effort we put in) because it proves love and sacrifice went into it — for the benefit of all.

Things should be costly (either in materials or the effort we put in) because it proves love and sacrifice went into it — for the benefit of all.

Past societies knew instinctively that cutting corners should be avoided. They made everything from lamp posts to phone boxes markers of civic pride.

If we don't put effort into the small things, doesn't that mean our culture has lost something?

If we don't put effort into the small things, doesn't that mean our culture has lost something?

If you cut out ornaments, you lose all the little things that make a place interesting.

Prague isn't beautiful because of its great monuments. It's all the "unnecessary" beauty: hand-carved statues and niches on every corner...

Prague isn't beautiful because of its great monuments. It's all the "unnecessary" beauty: hand-carved statues and niches on every corner...

Those old cities were the result of people shaping their environment organically over time, with a view to belonging there.

Every street corner tells a little story about its origin.

Every street corner tells a little story about its origin.

The modern, grid-plan street corner says nothing. Corners are simply where curtain walls meet.

The streets don't really belong to anyone.

The streets don't really belong to anyone.

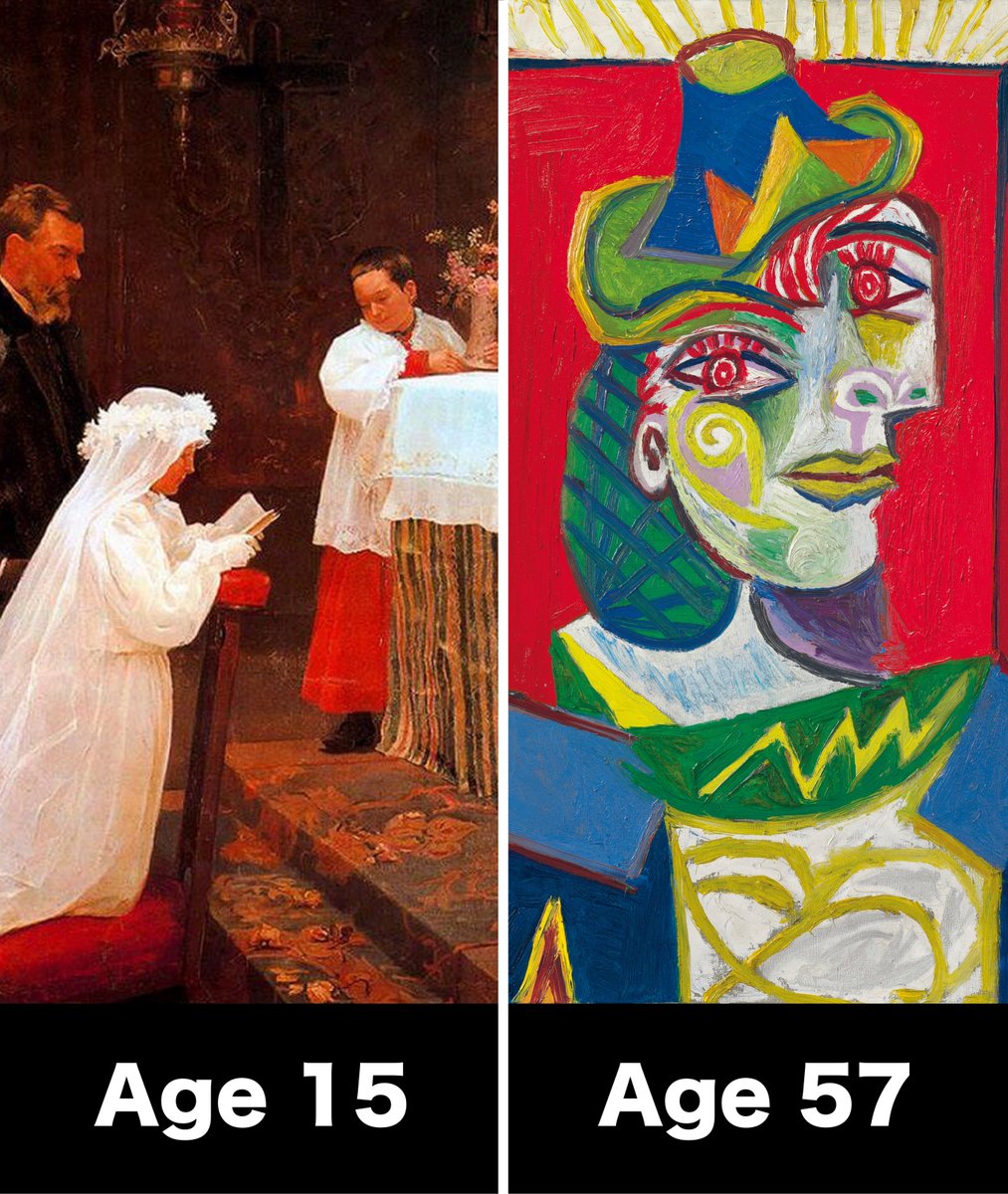

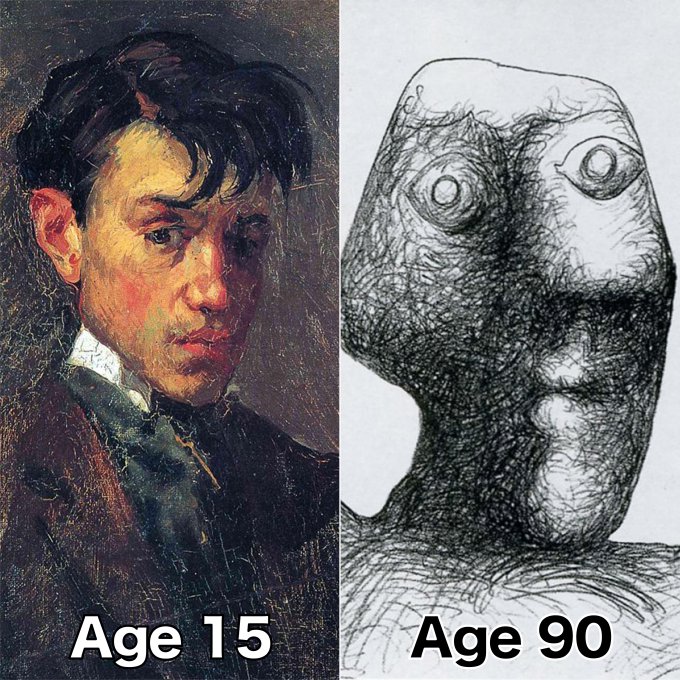

In so many aspects of life today, we're trying actively not to tell stories.

Companies no longer tell their complicated origin stories: logos must be immediately digestible and nothing more.

Companies no longer tell their complicated origin stories: logos must be immediately digestible and nothing more.

A world built on efficiency does this. When we forget about ornamentation, places and things become meaningless and monotonous.

Perhaps we've run out of meaning to assign to them?

Perhaps we've run out of meaning to assign to them?

The great Gothic facades of old told a thousand stories.

Maybe the problem is we no longer have anything to say...

Maybe the problem is we no longer have anything to say...

I go deeper on topics like this every week in my FREE newsletter — do not miss tomorrow!

60,000 people read it: art, history and culture 👇

culture-critic.com/welcome

60,000 people read it: art, history and culture 👇

culture-critic.com/welcome

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh