"How does humidity affect SARS-CoV-2 transmission?"

Whenever this question comes up, the answer I give is along the lines of “it’s complicated”.

So, what exactly do I mean (a 🧵)?

Whenever this question comes up, the answer I give is along the lines of “it’s complicated”.

So, what exactly do I mean (a 🧵)?

https://x.com/HMogan24/status/1820211262858432569

Context: When considering airborne transmission of a respiratory virus, numerous factors are involved.

They ALL matter.

Moreover, they are all independent. Meaning, a certain parameter may affect each factor differently.

They ALL matter.

Moreover, they are all independent. Meaning, a certain parameter may affect each factor differently.

Since the dawn of the field (1950s/60s), the airborne survival of viruses has been measured as a function of relative humidity (RH) and temperature. There are numerous reasons for this, such as to understand viral transmission and to inform about why the virus decays.

Another reason there was a focus on temperature and humidity was that people can both feel, as well as control, them. By understanding transmission via these parameters, it becomes readily possible to mitigate spread.

For SARS-CoV-2, numerous epidemiological studies have shown that transmission INCREASES at HIGH humidity.

nature.com/articles/s4159…

publichealth.jmir.org/2021/1/e20495/

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/P…

nature.com/articles/s4159…

publichealth.jmir.org/2021/1/e20495/

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/P…

For SARS-CoV-2, numerous epidemiological studies have shown that transmission INCREASES at LOW humidity.

aaqr.org/articles/aaqr-…

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/P…

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

aaqr.org/articles/aaqr-…

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/P…

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

So, what is going on here? Both of thesethings can not be true.

More curious is the specificity of the claims. For example, there has been reported both a strong increase and decrease below an RH of ~70%.

More curious is the specificity of the claims. For example, there has been reported both a strong increase and decrease below an RH of ~70%.

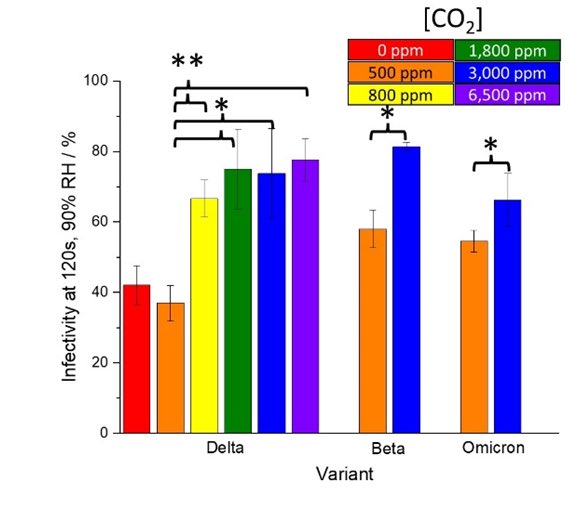

To understand what is happening, consider the following figure. Of the numerous processes involved in airborne transmission of a virus, RH affects a significant fraction. Moreover, the effect is often contradictory.

Consider just what is happening within the aerosol.

At high humidity:

-SARS-CoV-2 remains infectious longer

-the aerosol itself is larger

-the larger size causes it to settle out of the air faster

These processes are contradictory

At high humidity:

-SARS-CoV-2 remains infectious longer

-the aerosol itself is larger

-the larger size causes it to settle out of the air faster

These processes are contradictory

Consider the effect of RH on behavior. It the room gets too humid (or even too dry), people will proactively change their environment. For example, they may open a window leading to improved ventilation which in turn lowers the risk.

The body’s first line of defense to stop a respiratory infection is the layer of mucus and cilia on the surface of the bronchus epithelia. In dry air, the efficiency of this defense mechanism is lowered.

pnas.org/doi/full/10.10…

pnas.org/doi/full/10.10…

Mechanistically, there are reasons that high humidity both increases, and decreases, SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Likewise for low humidity.

As a result, it is unsurprising that both positive and negative correlations have been reported.

As a result, it is unsurprising that both positive and negative correlations have been reported.

In short, the effect of humidity on SARS-CoV-2 transmission is a mess.

If you have any questions, I’d be happy to try to answer them.

If you have any questions, I’d be happy to try to answer them.

I should also add that each of these general factors can be massively expanded. For example, "Immunity" encompasses all of the myriad of different virus/cell interactions.

@serehfas For example, people will turn on the AC in hot/humid conditions. Some AC units ventilate, others just push the, now cooler, air around more. Same action, wildly different changes in long distance transmission risk.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh