New interdisciplinary review was published on current Long COVID science, with a roadmap for science and policy!

It is written in plain language, so it's worth a read on its own, but I just want to pull out some highlights about what WE DO KNOW into a single thread...

1/many

It is written in plain language, so it's worth a read on its own, but I just want to pull out some highlights about what WE DO KNOW into a single thread...

1/many

This is definitely the definition for Long COVID I'll be explicitly using from now on: Long COVID is "the constellation of post-acute and long-term health effects caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection."

2/

2/

Long COVID "affects nearly every organ system, including the cardiovascular system, the nervous system, the endocrine system, the immune system, the reproductive system, and the gastrointestinal system."

It affects people regardless of age or pre-existing health status.

3/

It affects people regardless of age or pre-existing health status.

3/

The specifics of the risk have varied over time (as the virus and medicine both evolve), but one thing is clear: The risk of Long COVID accumulates with each infection.

People with three infections are more at risk than people with two infection, for example.

4/

People with three infections are more at risk than people with two infection, for example.

4/

The *risk* of LC is correlated with the severity of acute COVID, but because most of the people around the world have had mild COVID, these "mild" cases "constitute more than 90% of people with long COVID, despite their lower relative risk..."

5/

5/

The specifics of Long COVID are unclear, simply because studies have not been consistent enough to be comparable.

One of the biggest problems is labeling "remission" as "recovery," especially when many manifestations "are chronic conditions that last a lifetime."

6/

One of the biggest problems is labeling "remission" as "recovery," especially when many manifestations "are chronic conditions that last a lifetime."

6/

Simply put, we're facing a MASSIVE threat to global public health. This review looked at what is known—and what issues will have to be addressed going forward!

7/

7/

Fundamentally, one of the biggest problems with grasping the nature of Long COVID is the "dynamic nature of the pandemic itself, which gave rise to many variants and subvariants, each yielding potentially different rates of long COVID"

8/

8/

But you know what is really interesting? If we stick to the absolute bare-minimum definition (having one of three clusters of symptoms three months after infection), we consistently see that AT LEAST *7% of the population* is impacted.

9/

9/

The global count of people affected by Long COVID is jarring: even only accounting for symptomatic cases and the most-likely outcomes, they "estimated a cumulative global incidence of long COVID by the end of 2023 of approximately 400 million."

400 MILLION.

10/

400 MILLION.

10/

And you know what else makes it challenging to estimate the global incidence of Long COVID? We don't yet know what risks "are not yet manifest and may emerge years or decades after infection."

This is a pressing global health issue.

11/

This is a pressing global health issue.

11/

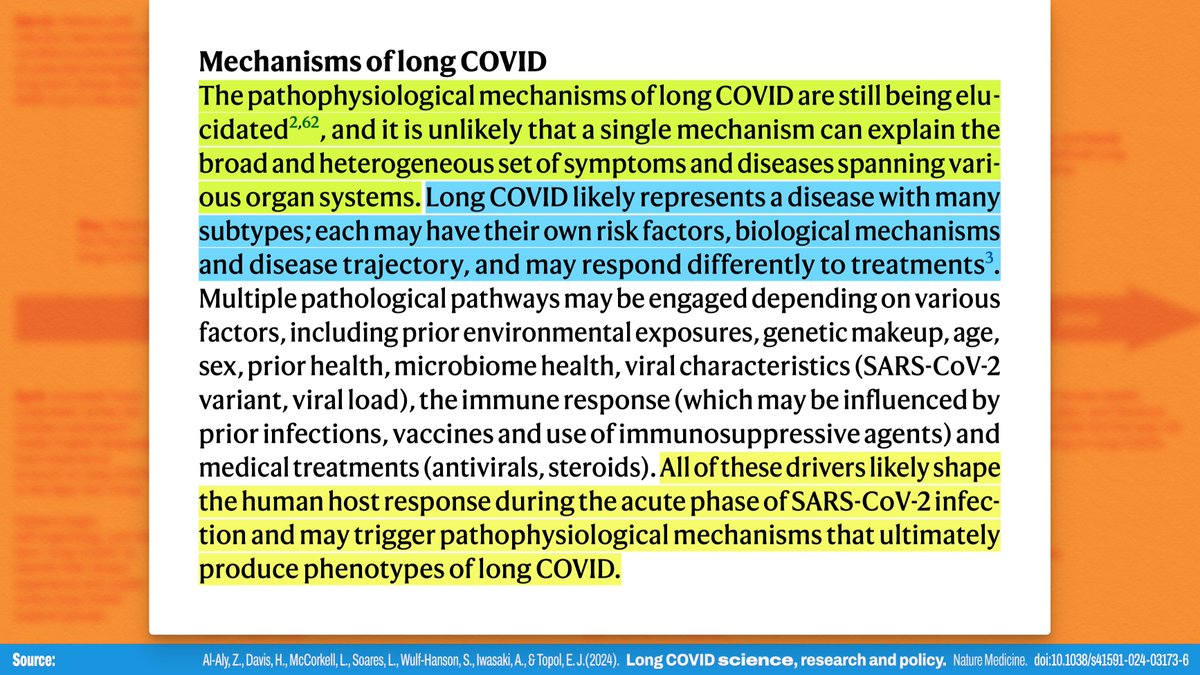

What causes Long COVID? Why does it occur?

Well, the specifics are still being figured out. There's not yet a clean answer to that question. All we do know is that it can involve many different systems, and many different variables affect outcomes.

12/

Well, the specifics are still being figured out. There's not yet a clean answer to that question. All we do know is that it can involve many different systems, and many different variables affect outcomes.

12/

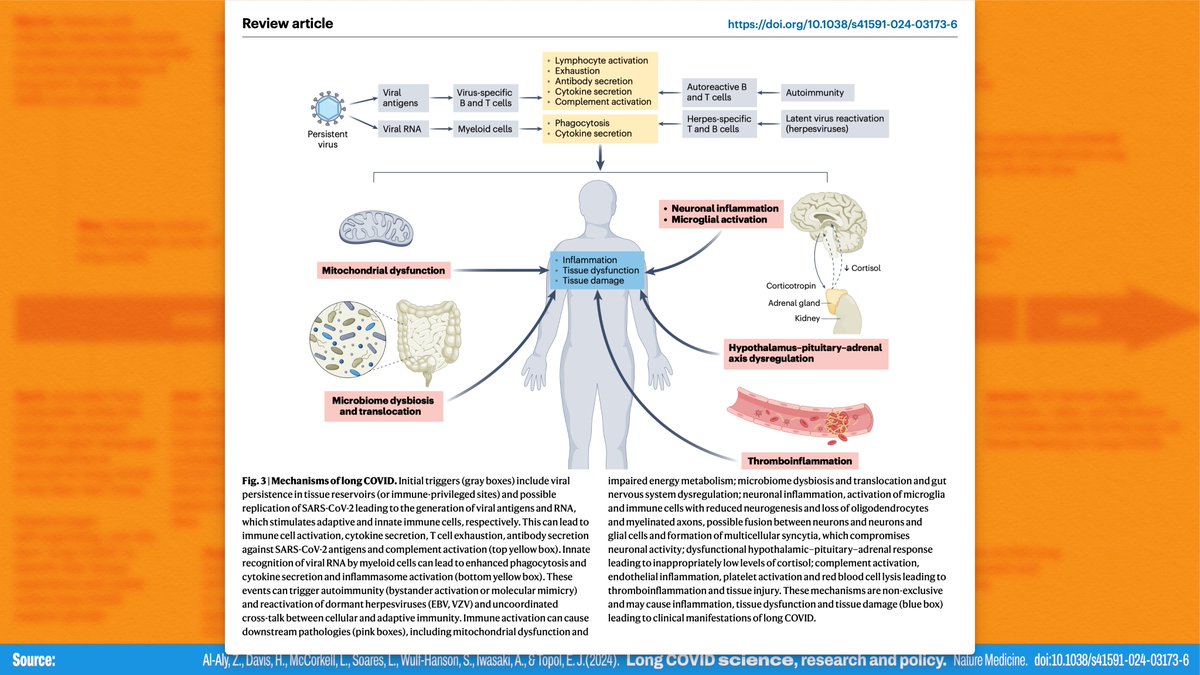

There are, however, some more-salient pathways that have been proposed, "including viral persistence, immune dysregulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, complement dysregulation, prothrombotic inflammation and microbiome dysbiosis"

13/

13/

Viral persistence is of particular concern, because persistence of "either replicating virus or viral RNA or protein fragments" in certain tissues "may be common" and "may trigger chronic low-grade inflammation and tissue injury."

14/

14/

Viral persistence is of particular note for further investigation, because studies "have demonstrated persistence of the virus in extrapulmonary sites, including the brain and coronary arteries, of individuals with severe COVID-19."

15/

15/

But here's the thing: Even if SARS-CoV-2 *isn't* directly infecting the brain, we DO know that "a transient respiratory infection with SARS-CoV-2 induces prolonged neuroinflammatory responses" and *brain fog* is associated with "disrupted blood-brain barriers."

NOT GOOD.

16/

NOT GOOD.

16/

When it comes to the immune system "abnormalities in the immune system have been documented in" pwLC, including a heightened antibody response to various herpesviruses, "exhausted T cell responses," uncoordinated adaptive immunity, and autoimmune responses.

17/

17/

Note that some of the vascular, endocrine, and GI impacts of LC can also have a DIRECT impact on nervous system and brain function.

(IMO, LC is primarily neurological, with the overarching condition being triggered by dysregulation in these other areas.)

18/

(IMO, LC is primarily neurological, with the overarching condition being triggered by dysregulation in these other areas.)

18/

How can LC be prevented? The best way to avoid Long COVID is to avoid SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Masking and ventilation "can reduce the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and... the risk of long COVID."

Vaccines ALSO reduce the risk of (but don't entirely *prevent*) LC.

19/

Masking and ventilation "can reduce the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and... the risk of long COVID."

Vaccines ALSO reduce the risk of (but don't entirely *prevent*) LC.

19/

There are some drugs in the works that have been shown to be useful in acute COVID, but it's still not entirely clear if they have a significant impact on the risk of Long COVID.

The best thing you can do for yourself is to not have anymore SARS-CoV-2 infections.

20/

The best thing you can do for yourself is to not have anymore SARS-CoV-2 infections.

20/

What about treatments? There is nothing yet, other than a few promising leads.

Current treatment for Long COVID is based on evidence for "treating similar symptomatology from other conditions," including ME/CFS and Gulf War illness.

So, nothing specific yet.

21/

Current treatment for Long COVID is based on evidence for "treating similar symptomatology from other conditions," including ME/CFS and Gulf War illness.

So, nothing specific yet.

21/

All of these issues are compounded by "lack of widespread recognition and understanding of long COVID among medical professionals" and a "general pervasive pandemic fatigue with an urge to 'move on'."

Unfortunately, the virus is unaware the pandemic was DECLARED "over".

22/

Unfortunately, the virus is unaware the pandemic was DECLARED "over".

22/

The impacts have been SIGNIFICANT.

- 1 in 4 pwLC have to "limit activities outside work in order to continue working."

- The increased demand created by LC "exacerbates existing pressures on health systems."

- There are "wide and deep ramifications on national economies."

23/

- 1 in 4 pwLC have to "limit activities outside work in order to continue working."

- The increased demand created by LC "exacerbates existing pressures on health systems."

- There are "wide and deep ramifications on national economies."

23/

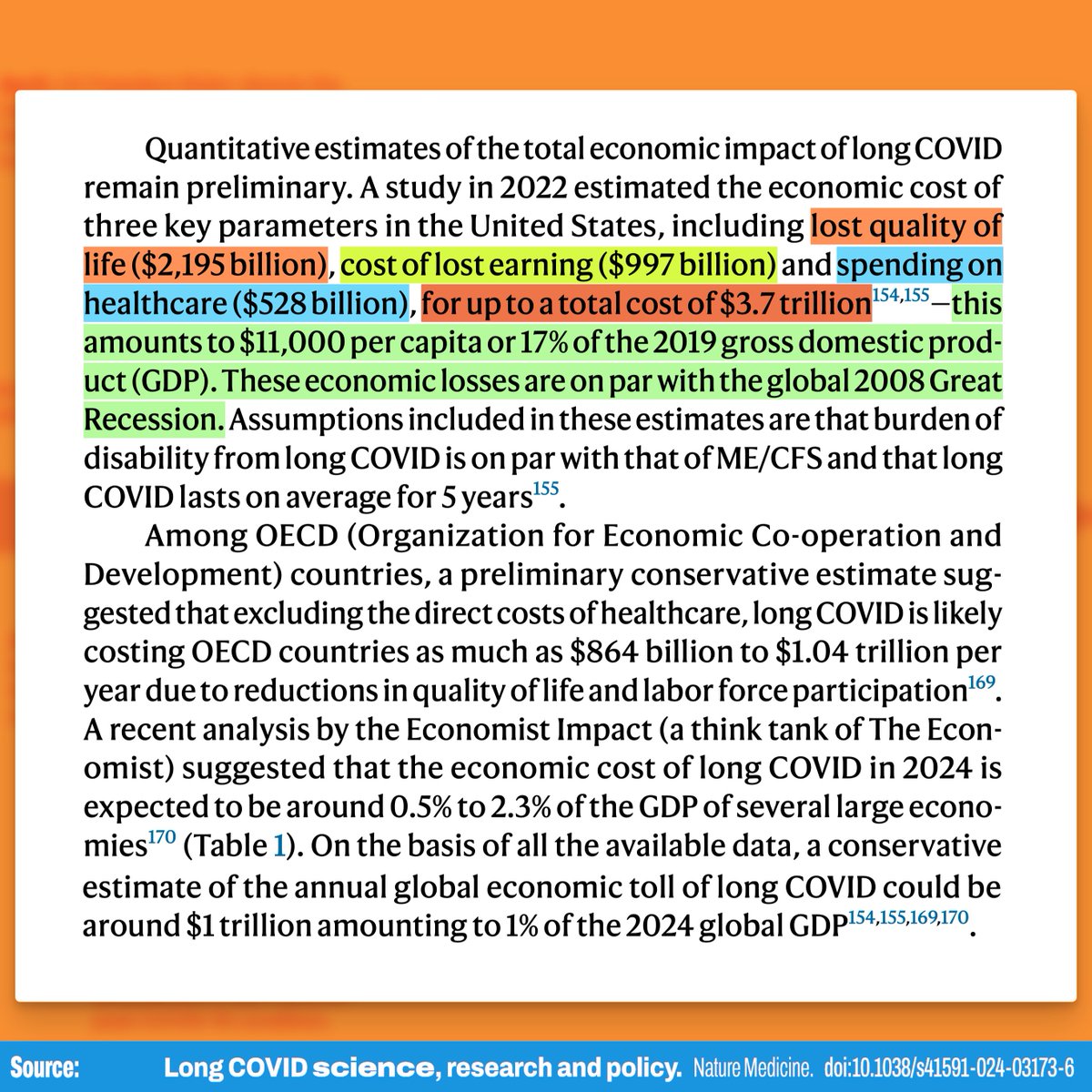

The economic losses in the United States alone are "on par with the global 2008 Great Recession," incurring financial losses of around $11,000 per capita.

And this is with the assumption that, for those who develop Long COVID, it will only last five years.

24/

And this is with the assumption that, for those who develop Long COVID, it will only last five years.

24/

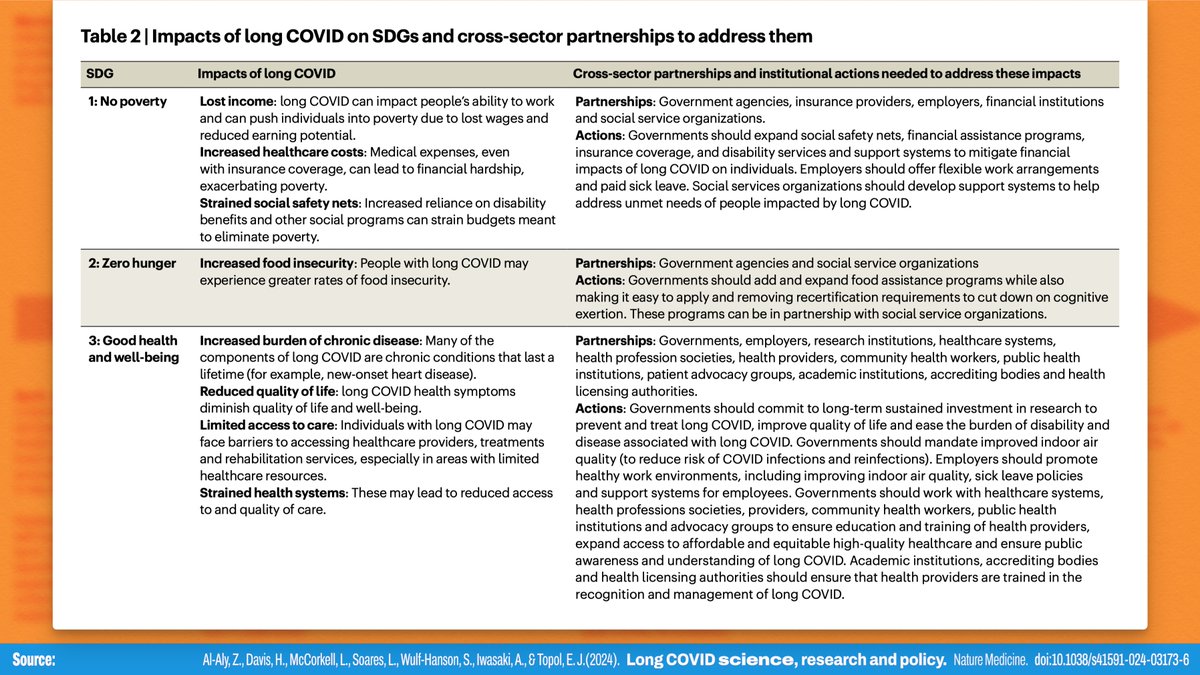

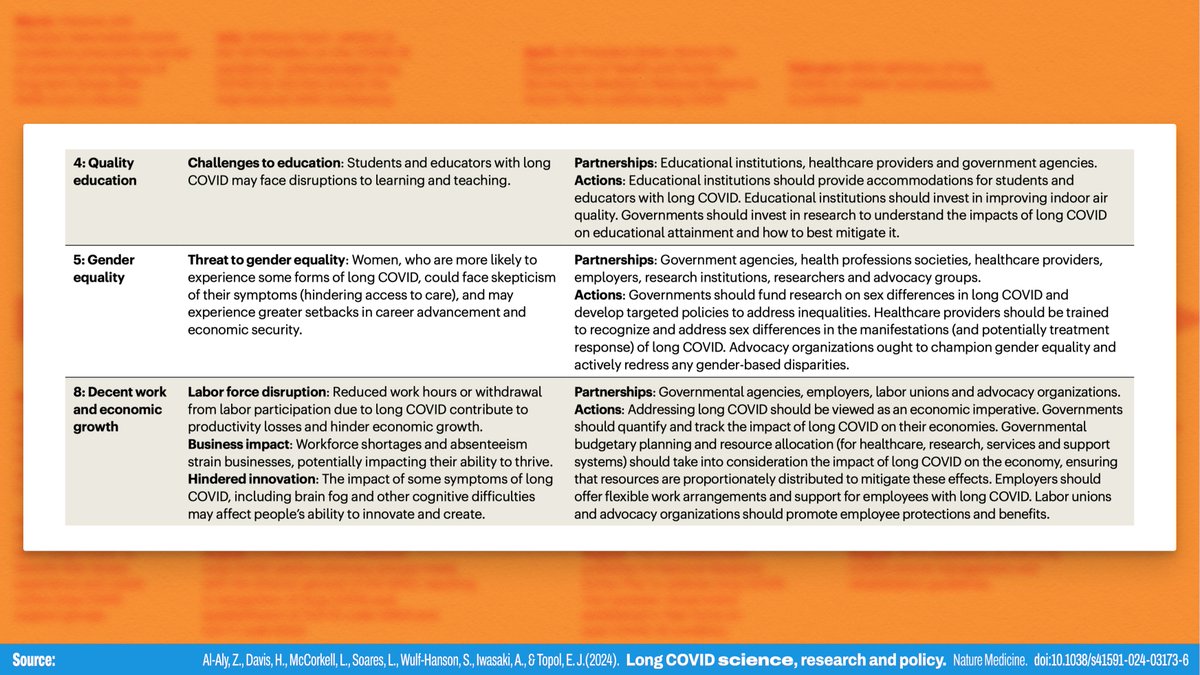

So... what do we do?

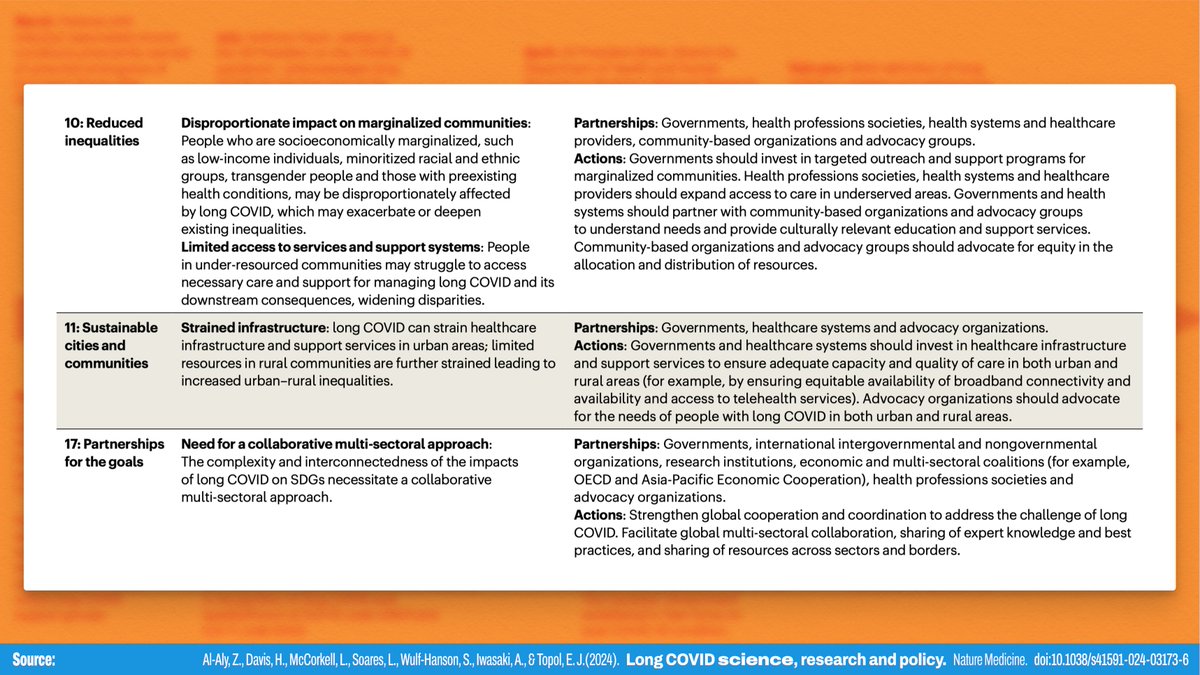

The rest of the paper lays out detailed research and policy roadmaps we can follow to navigate this crisis, and it's worth a read:

The path forward isn't easy, but this is not a problem that CANNOT be ignored.

25/25 nature.com/articles/s4159…

The rest of the paper lays out detailed research and policy roadmaps we can follow to navigate this crisis, and it's worth a read:

The path forward isn't easy, but this is not a problem that CANNOT be ignored.

25/25 nature.com/articles/s4159…

*This is a problem that CANNOT be ignored.

One of my absolute worst habits is rephrasing a sentence without making sure I removed all the redundant words. 🤦♂️

26/25

One of my absolute worst habits is rephrasing a sentence without making sure I removed all the redundant words. 🤦♂️

26/25

Agreed! It seems likely to be an underestimate.

I think they were aiming to define the bare minimum scope of what is actually known fairly definitively, and based on that the floor of the estimate is 400 million. It’s a good strategy from a policy advocacy perspective!

27/25

I think they were aiming to define the bare minimum scope of what is actually known fairly definitively, and based on that the floor of the estimate is 400 million. It’s a good strategy from a policy advocacy perspective!

27/25

https://twitter.com/bcarfree/status/1822100408514519315

Here is the entire thread summarizing the paper on one page: readwise.io/reader/shared/…

Note that they found an apparent disparity between LC in adults (6-7%) and children (~1%)!

HOWEVER, I do think this disparity may represent a significant underreporting of LC symptoms in children. Why?

While the severe ME/CFS phenotype of LC has very overt symptoms,…

28/25

HOWEVER, I do think this disparity may represent a significant underreporting of LC symptoms in children. Why?

While the severe ME/CFS phenotype of LC has very overt symptoms,…

28/25

https://twitter.com/jeffcavanagh1/status/1822332008368058716

…if a child’s symptoms manifest as moderate cognitive impairment and fatigue, they may not even realize something is wrong.

An adult realizes the issue when they’re no longer able to do their job. How many kids think school just becomes MUCH more challenging with age?

29/25

An adult realizes the issue when they’re no longer able to do their job. How many kids think school just becomes MUCH more challenging with age?

29/25

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

![“8. Performance of Nuclear Power Plants Affected by the Blackout On August 14, 2003, nine U.S. nuclear power plants experienced rapid shutdowns (reactor trips) as a consequence of the power outage. Seven nuclear power plants in Canada operating at high power levels at the time of the event also experienced rapid shutdowns. […]. Many non-nuclear generating plants in both countries also tripped during the event. Numerous other nuclear plants observed disturbances on the electrical grid but continued to generate electrical power without interruption. […] - The severity of the grid transient...](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/G0Q9wDEXkAAknYM.jpg)