What do the Washington Post, Brookings, The Atlantic, and Business Insider have in common?

They all employ credulous writers who don't read about the things they write about.

The issue? Attacks on laptop-based notetaking🧵

They all employ credulous writers who don't read about the things they write about.

The issue? Attacks on laptop-based notetaking🧵

Each of these outlets (among many others, unfortunately) reported on a a 2014 study by Mueller and Oppenheimer, in which it was reported that laptop-based note-taking was inferior to longhand note-taking for remembering content.

The evidence for this should not have been considered convincing.

In the first study, a sample of 67 students was randomized to watch and take notes on different TED talks and then they were assessed on factual or open-ended questions. The result? Worse open-ended performance:

In the first study, a sample of 67 students was randomized to watch and take notes on different TED talks and then they were assessed on factual or open-ended questions. The result? Worse open-ended performance:

The laptop-based note-takers didn't do worse when it came to factual content, but they did so worse when it came to the open-ended questions.

The degree to which they did worse should have been the first red flag: d = 0.34, p = 0.046.

The degree to which they did worse should have been the first red flag: d = 0.34, p = 0.046.

The other red flag should have been that there was no significant interaction between the mean difference and the factual and conceptual condition (p ≈ 0.25). Strangely, that went unnoted, but I will return to it.

The authors sought to explain why there wasn't a difference in factual knowledge about the TED talks while there was one in ability to describe stuff about it/to provide open-ended, more subjective answers.

Simple: Laptops encouraged verbatim, not creative note-taking.

Simple: Laptops encouraged verbatim, not creative note-taking.

Before going on to study 2: Do note that all of these bars lack 95% CIs. They show standard errors, so approximately double them in your head if you're trying to figure out which differences are significant.

OK, so the second study added an intervention.

OK, so the second study added an intervention.

The intervention asked people using laptops to try to not take notes verbatim. This intervention totally failed with a stunningly high p-value as a result:

In terms of performance, there was once again nothing to see for factual recall. But, the authors decided to interpret a significant difference between the laptop-nonintervention participants and longhand participants in the open-ended questions as being meaningful.

But it wasn't, and the authors should have known it! Throughout this paper, they repeatedly bring up interaction tests, and they know that the interaction by the intervention did nothing, so they shouldn't have taken it. They should have affirmed no significant difference!

The fact that the authors knew to test for interactions and didn't was put on brilliant display in study 3, where they did a different intervention in which people were asked to study or not study their notes before testing at a follow-up.

Visual results:

Visual results:

This section is like someone took a shotgun to the paper and the buckshot was p-values in the dubious, marginal range, like a main effect with a p-value of 0.047, a study interaction of p = 0.021, and so on

It's just a mess and there's no way this should be believed. Too hacked!

It's just a mess and there's no way this should be believed. Too hacked!

And yet, this got plenty of reporting.

So the idea is out there, it's widely reported on. Lots of people start saying you should take notes by hand, not with a laptop.

But the replications start rolling in and it turns out something is wrong.

So the idea is out there, it's widely reported on. Lots of people start saying you should take notes by hand, not with a laptop.

But the replications start rolling in and it turns out something is wrong.

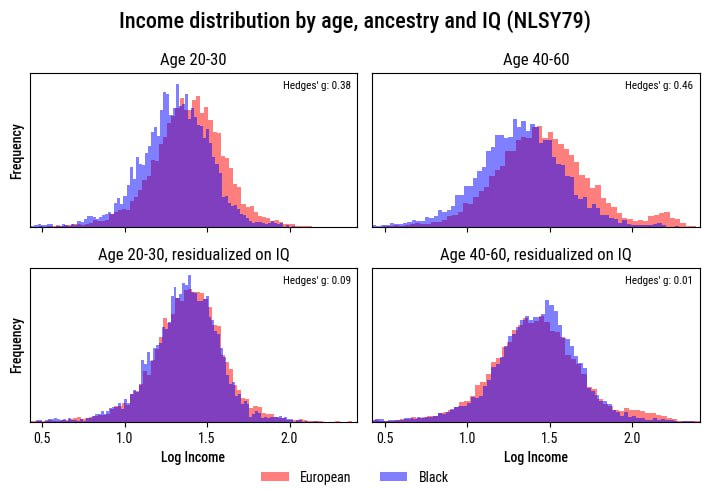

In a replication of Mueller and Oppenheimer's first study with a sample that was about twice as large, Urry et al. failed to replicate the key performance-related results.

Verbatim note copying and longer notes with laptops? Both confirmed. The rest? No.

Verbatim note copying and longer notes with laptops? Both confirmed. The rest? No.

So then Urry et al. did a meta-analysis. This was very interesting, because apparently they found that Mueller and Oppenheimer had used incorrect CIs and their results were actually nonsignificant for both types of performance.

Oh and the rest of the lit was too:

Oh and the rest of the lit was too:

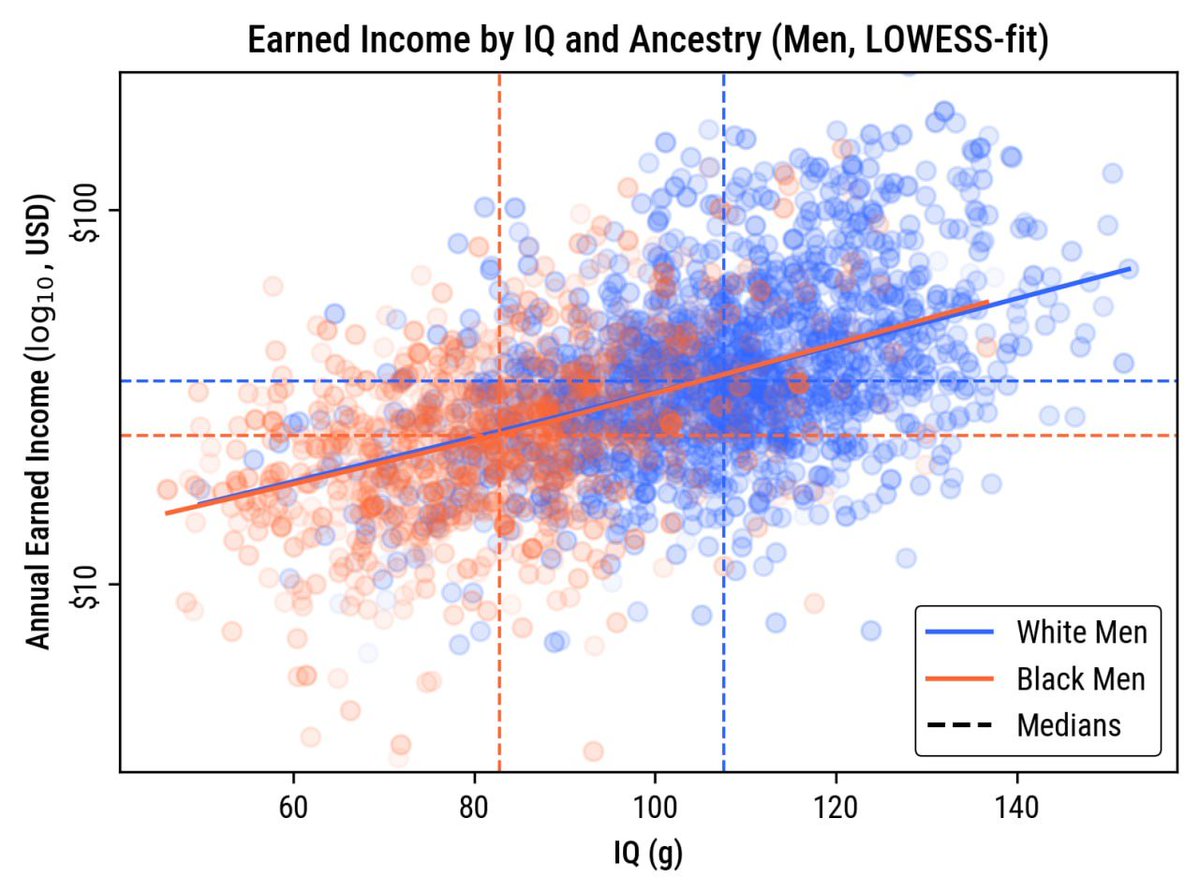

Meta-analytically, using a laptop definitely led to higher word counts in notes and more verbatim note-taking, but the performance results just weren't there.

The closest thing we get in the meta-analysis to performance going up is that maybe conceptual performance went up a tiny bit (nonsignificant, to be clear), but who even knows if that assessment's fair

That's important, since essays and open-ended questions are frequently biased

That's important, since essays and open-ended questions are frequently biased

So, ditch the laptop to take notes by hand?

I wouldn't say to do that just yet.

But definitely ditch the journalists who don't tell you how dubious the studies they're reporting on actually are.

I wouldn't say to do that just yet.

But definitely ditch the journalists who don't tell you how dubious the studies they're reporting on actually are.

Sources:

Postscript: A study with missing condition Ns, improperly-charted SEs, and the result that laptop notes are worse only for laptop-based test-taking but not taking tests by hand. Probably nothing: journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/09…

journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.11…

journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00…

Postscript: A study with missing condition Ns, improperly-charted SEs, and the result that laptop notes are worse only for laptop-based test-taking but not taking tests by hand. Probably nothing: journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/09…

journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.11…

journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh