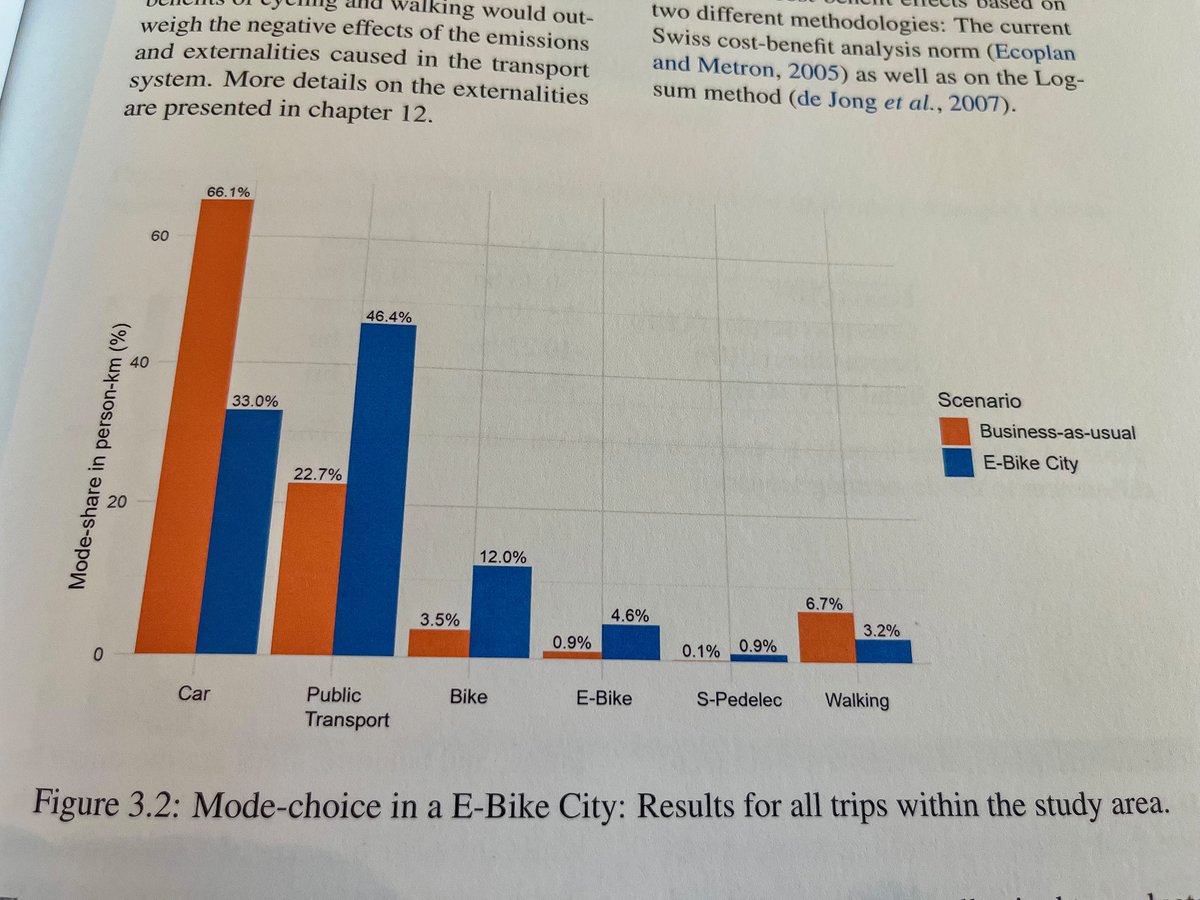

What does an AI tool teach us about accelerating the urgent shift to cycling? We must stop engaging in bad faith arguments over bike lanes. We won’t—and don’t need to—convince everyone in the comment section. Our precious time and energy are better spent on the bigger picture. 🧵

Rather we should share our vision of a liveable future; sparking a values-based conversation on our aspirations, on which there’s a lot of consensus: on safety, health, greenery, equity, sustainability, prosperity. Once we agree on the destination, we can debate how to get there.

We must expand our movement to bring in those left behind by car dependence. There's a coalition waiting to be formed, especially the young and old, women, and people with disabilities or lower incomes. Many would hop on a bike if it didn’t require dodging cars from door-to-door.

We must rise above the culture war separating us into modes and leading to inaction. There is a latent demand waiting to be activated and numbers that will support politicians willing to change the status quo. Our mission is to ensure this silent majority is heard loud and clear.

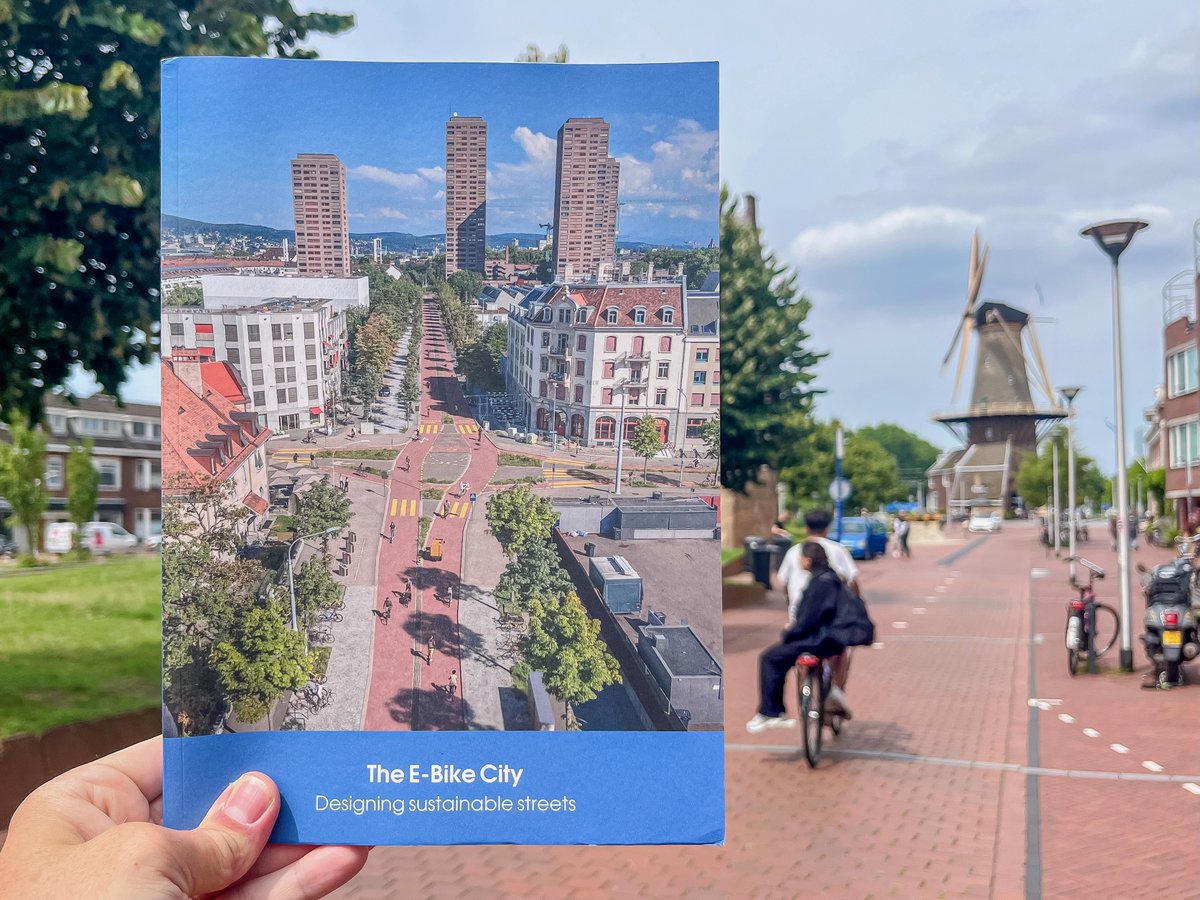

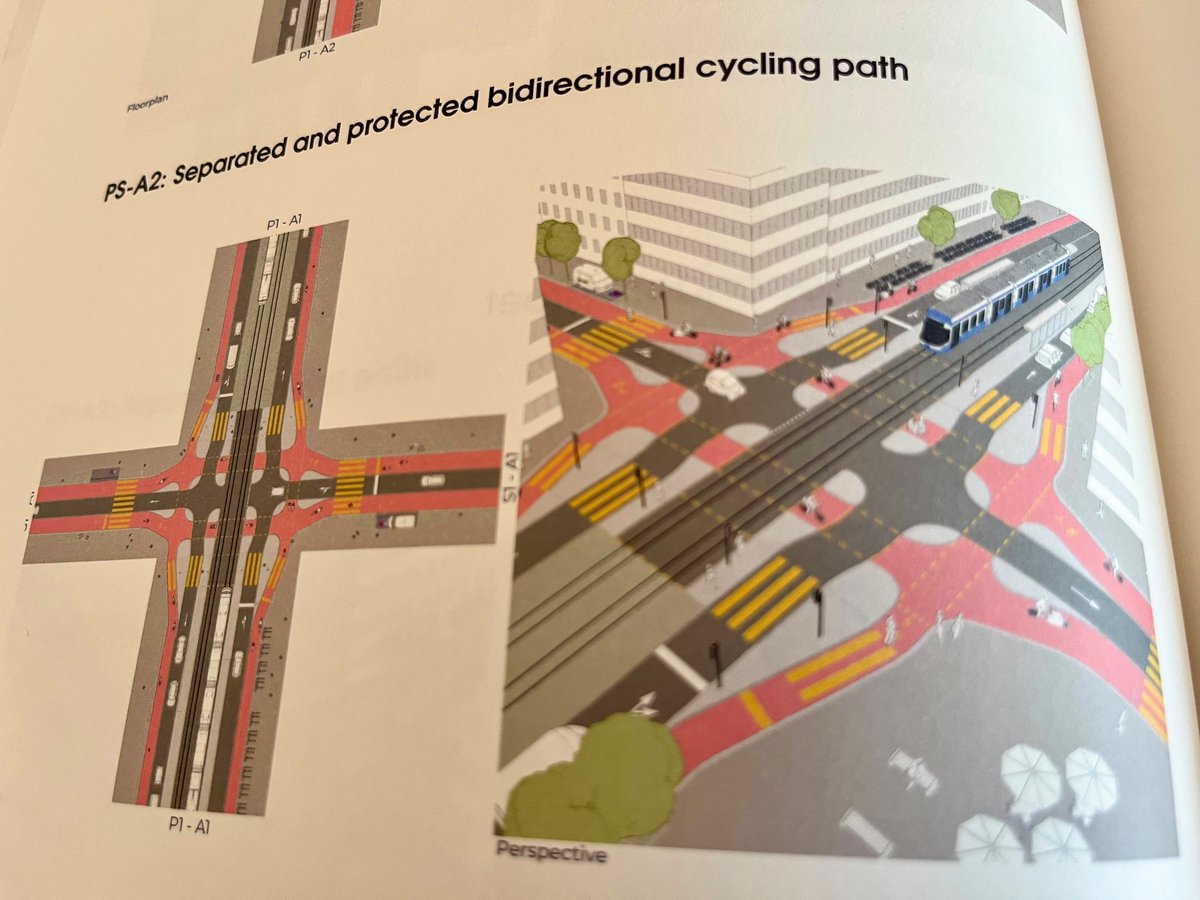

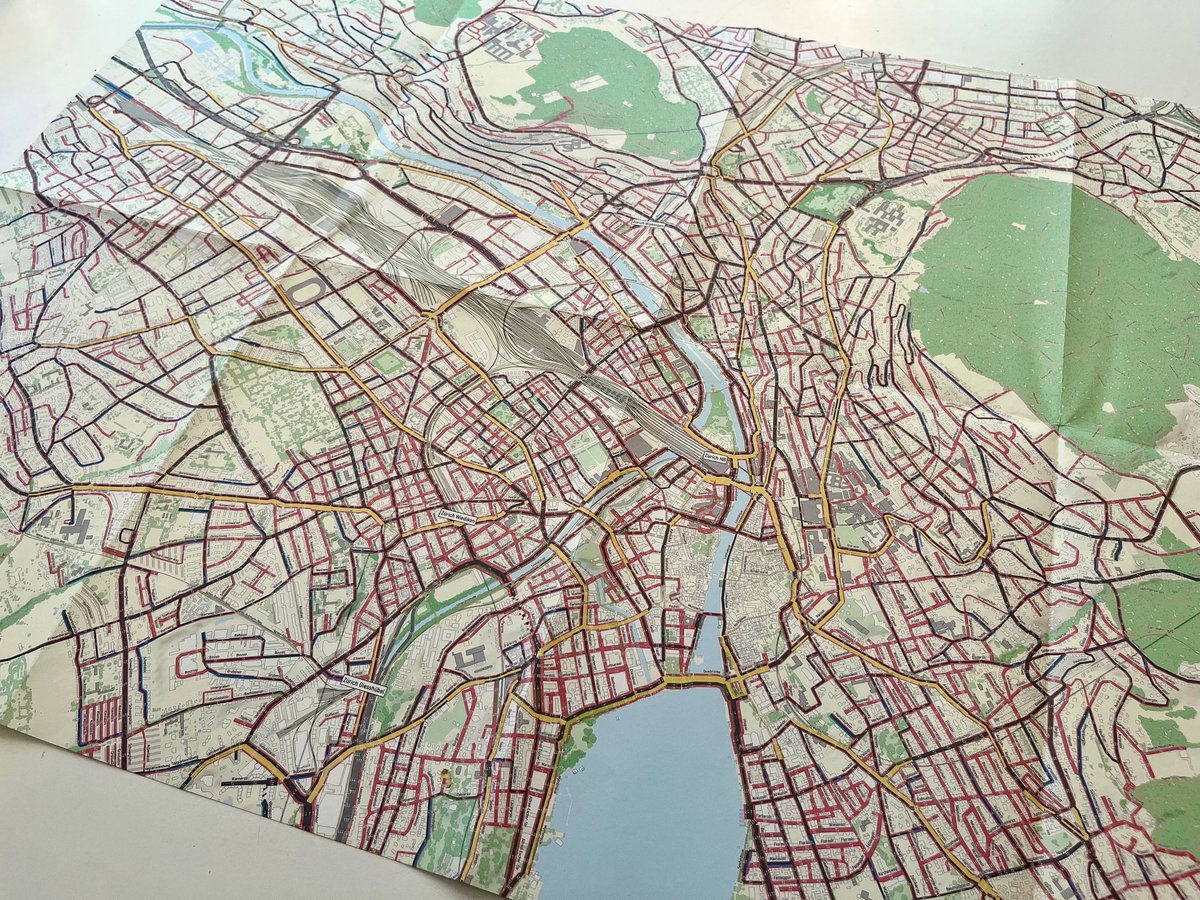

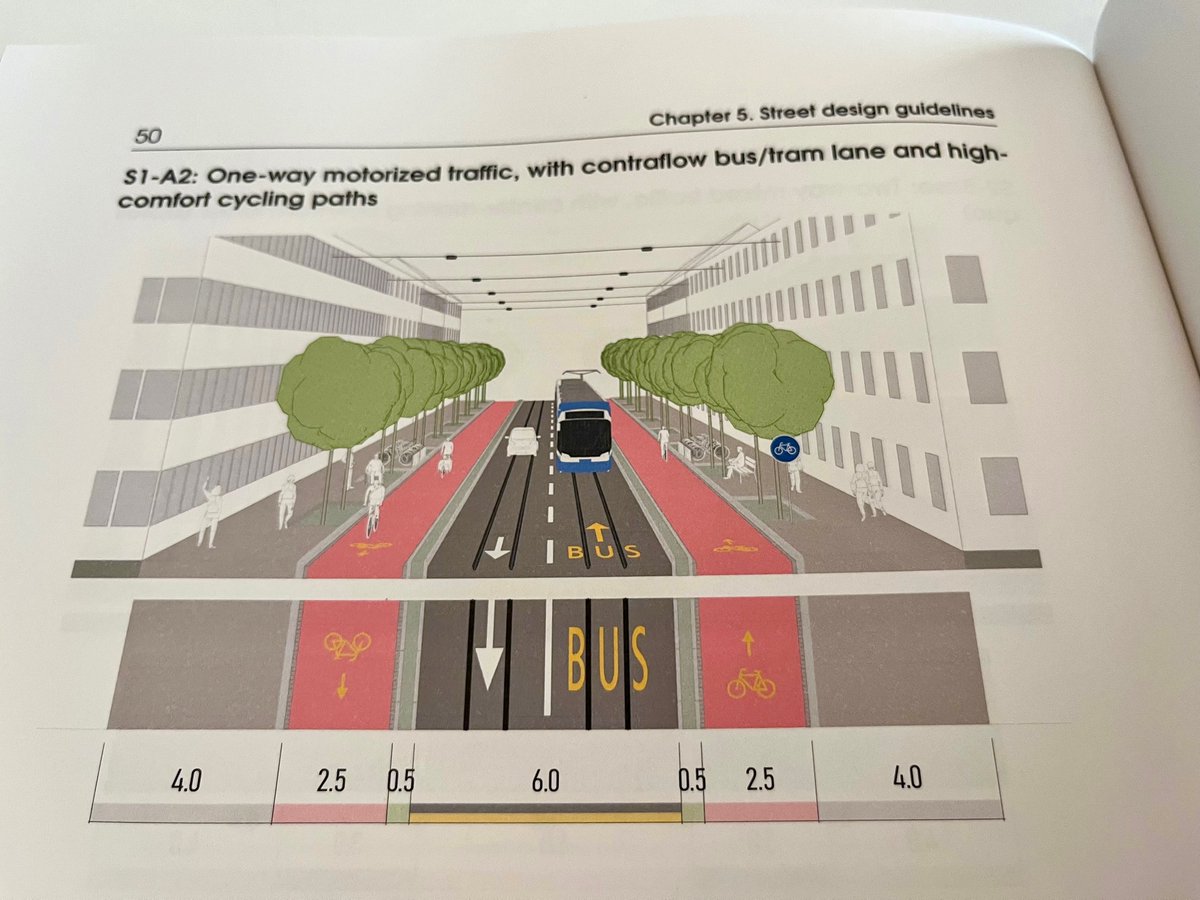

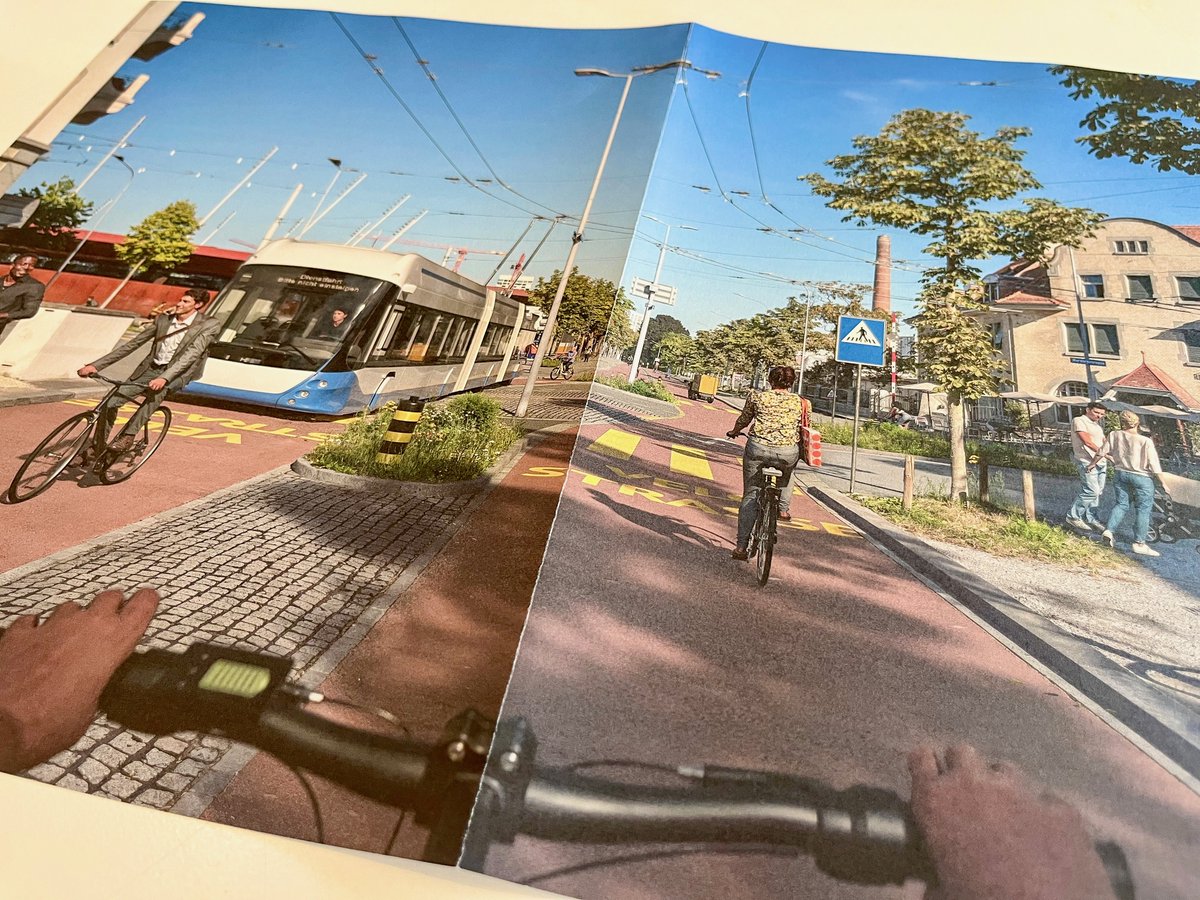

The five images in this post weren’t created by AI. They’re photos of places where the @Cycling_Embassy has worked... Pioneers that reframed the conversation, and asked, “Not what your city can do for cycling, but what cycling can do for your city.” WATCH:

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh