Dutch-Canadian authors and urban mobility advocates who strive to communicate the benefits of happier, healthier, more human-scale cities.

3 subscribers

How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

For years, Berliners have complained about the rise of traffic on side streets not designed to carry such volumes. While their 2018 Mobility Act promised a shift toward alternatives, progress on traffic calming has been slow and uneven. In that vacuum, residents began organising.

For years, Berliners have complained about the rise of traffic on side streets not designed to carry such volumes. While their 2018 Mobility Act promised a shift toward alternatives, progress on traffic calming has been slow and uneven. In that vacuum, residents began organising.

Breda has long been a car city, and in their infinite wisdom, its post-war planners filled in and rerouted the Mark River around the centre to make room for the car. But now, the waterway is being brought bank into the city, while introducing plants, trees and fauna on its banks.

Breda has long been a car city, and in their infinite wisdom, its post-war planners filled in and rerouted the Mark River around the centre to make room for the car. But now, the waterway is being brought bank into the city, while introducing plants, trees and fauna on its banks.

Robertson first proposed reallocating one travel lane from cars to bikes on the Burrard Bridge, and the blowback began. Media outlets published scathing editorials. Residents voiced their vehement opposition. Business leaders said he was choking the lifeblood out of the downtown.

Robertson first proposed reallocating one travel lane from cars to bikes on the Burrard Bridge, and the blowback began. Media outlets published scathing editorials. Residents voiced their vehement opposition. Business leaders said he was choking the lifeblood out of the downtown.

After mixed results with demonstration projects in Tilburg and The Hague (see prior posts), the national government took their third attempt to Delft, a city with a reputation for innovation. Learning from their mistakes, rather than a single route, a complete grid was envisaged.

After mixed results with demonstration projects in Tilburg and The Hague (see prior posts), the national government took their third attempt to Delft, a city with a reputation for innovation. Learning from their mistakes, rather than a single route, a complete grid was envisaged.

Adopted as citywide policy in 2018, it defines how the public realm is designed: from pavers to lighting, furniture, trees; even details like gullies and edging. The aim is streets that are functional, durable, safe and visually consistent, without tipping into fussy over-design.

Adopted as citywide policy in 2018, it defines how the public realm is designed: from pavers to lighting, furniture, trees; even details like gullies and edging. The aim is streets that are functional, durable, safe and visually consistent, without tipping into fussy over-design.

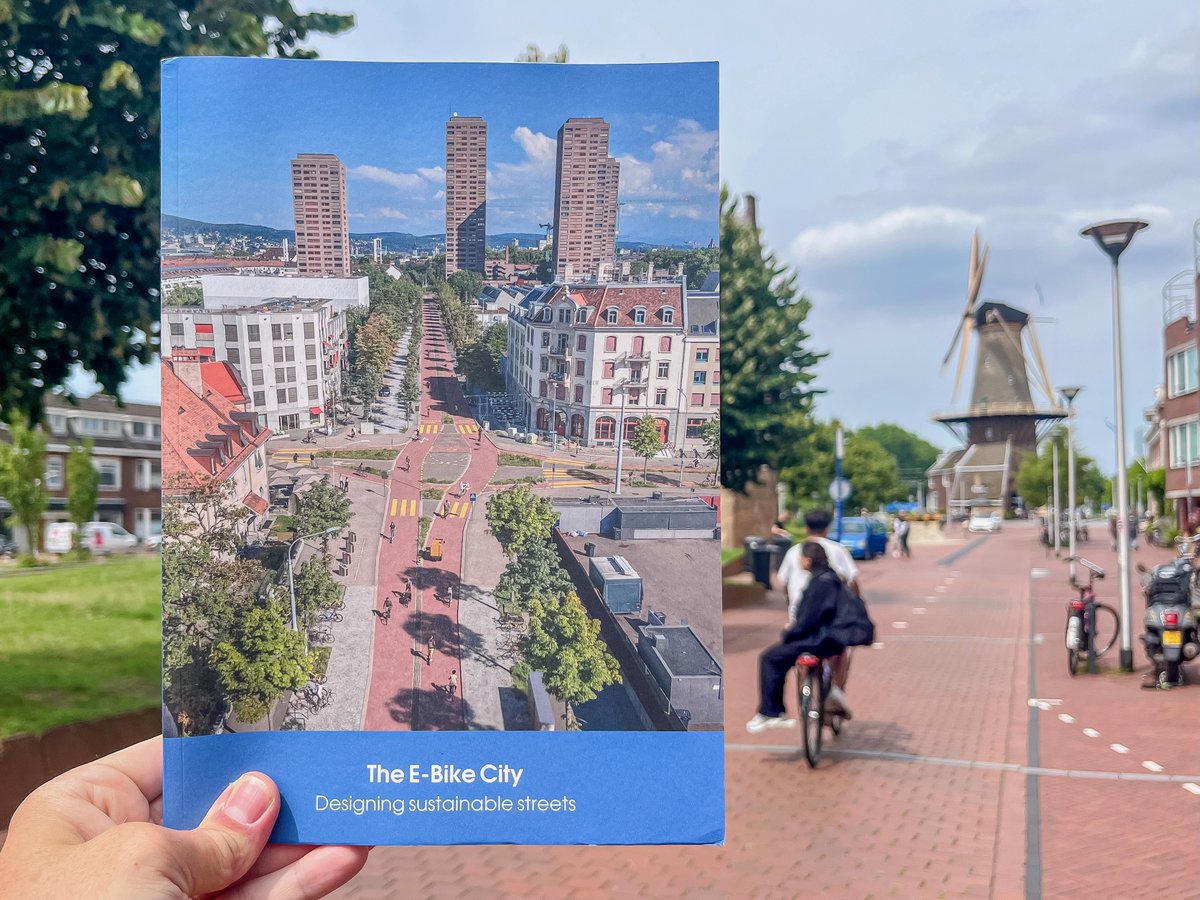

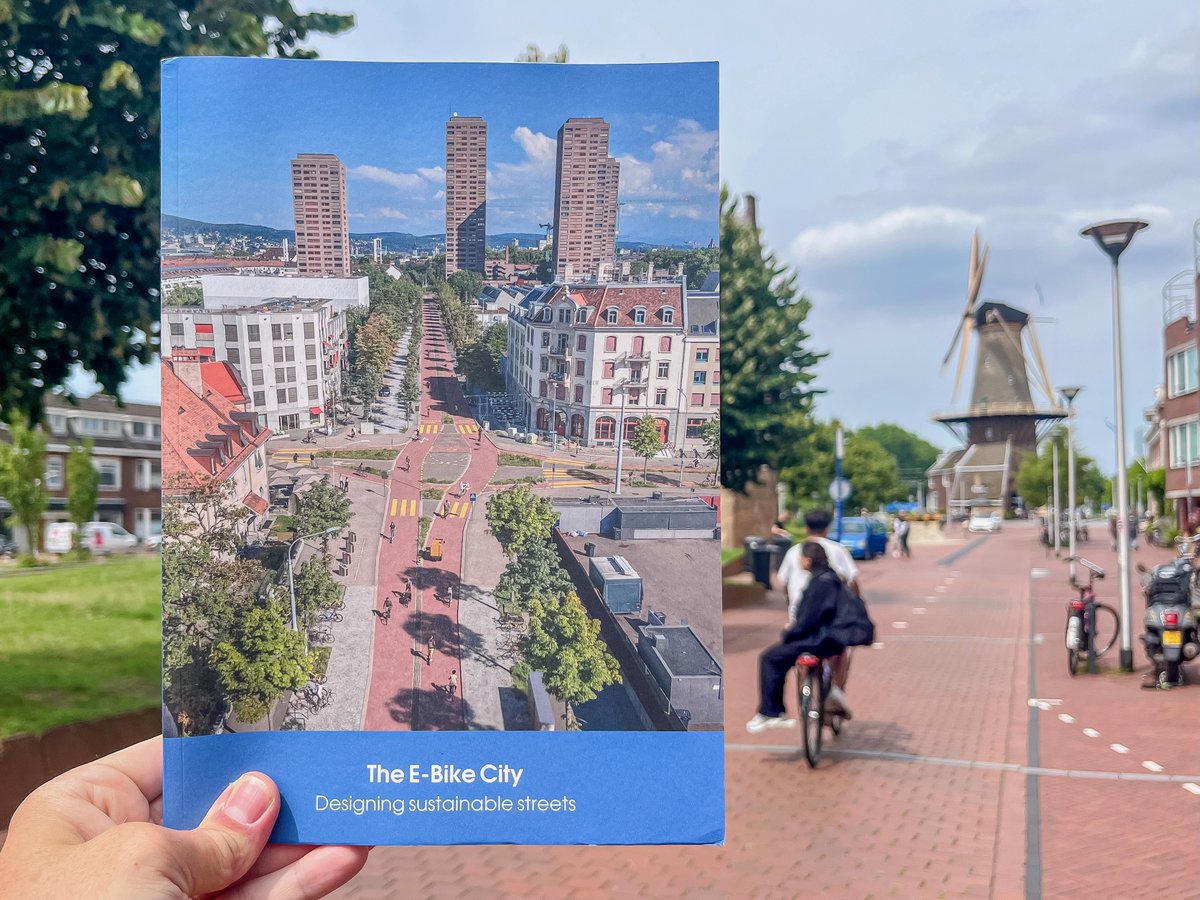

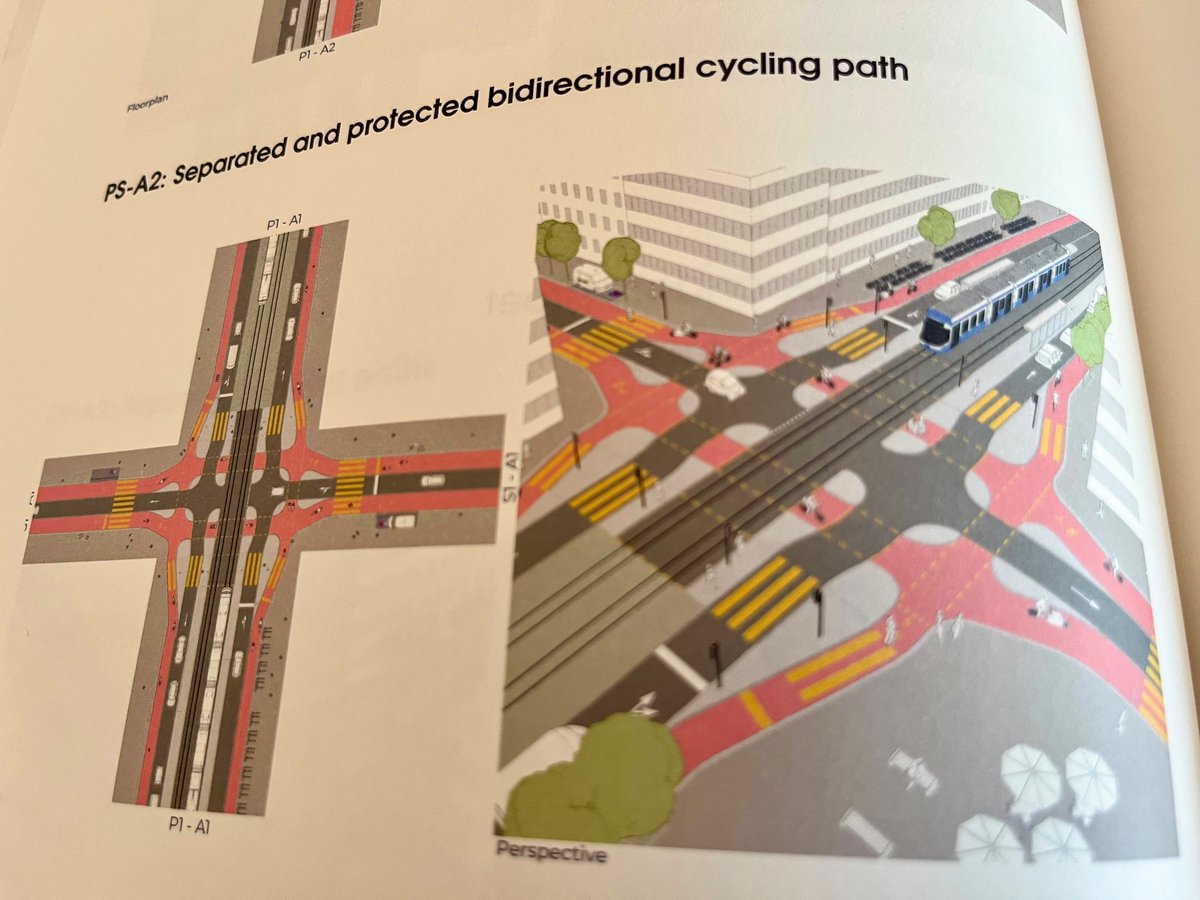

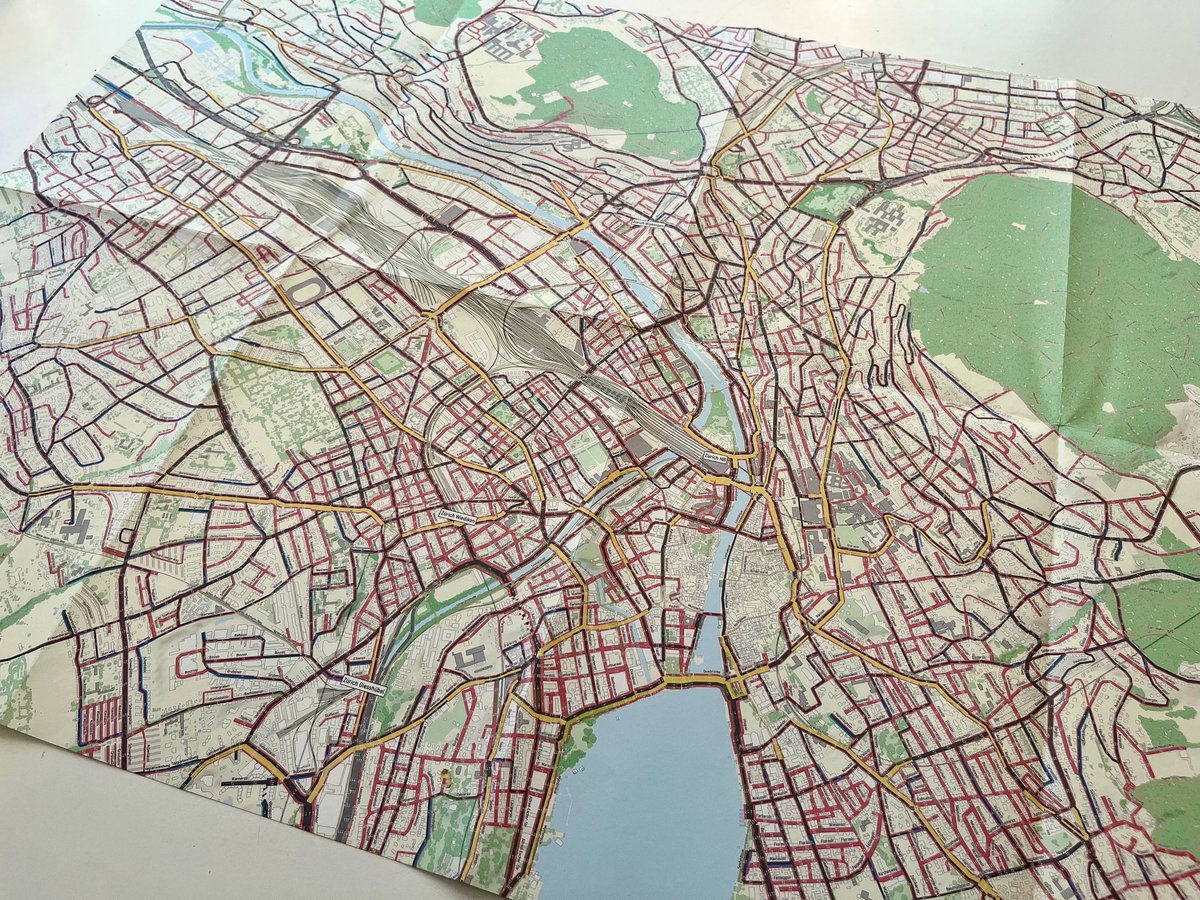

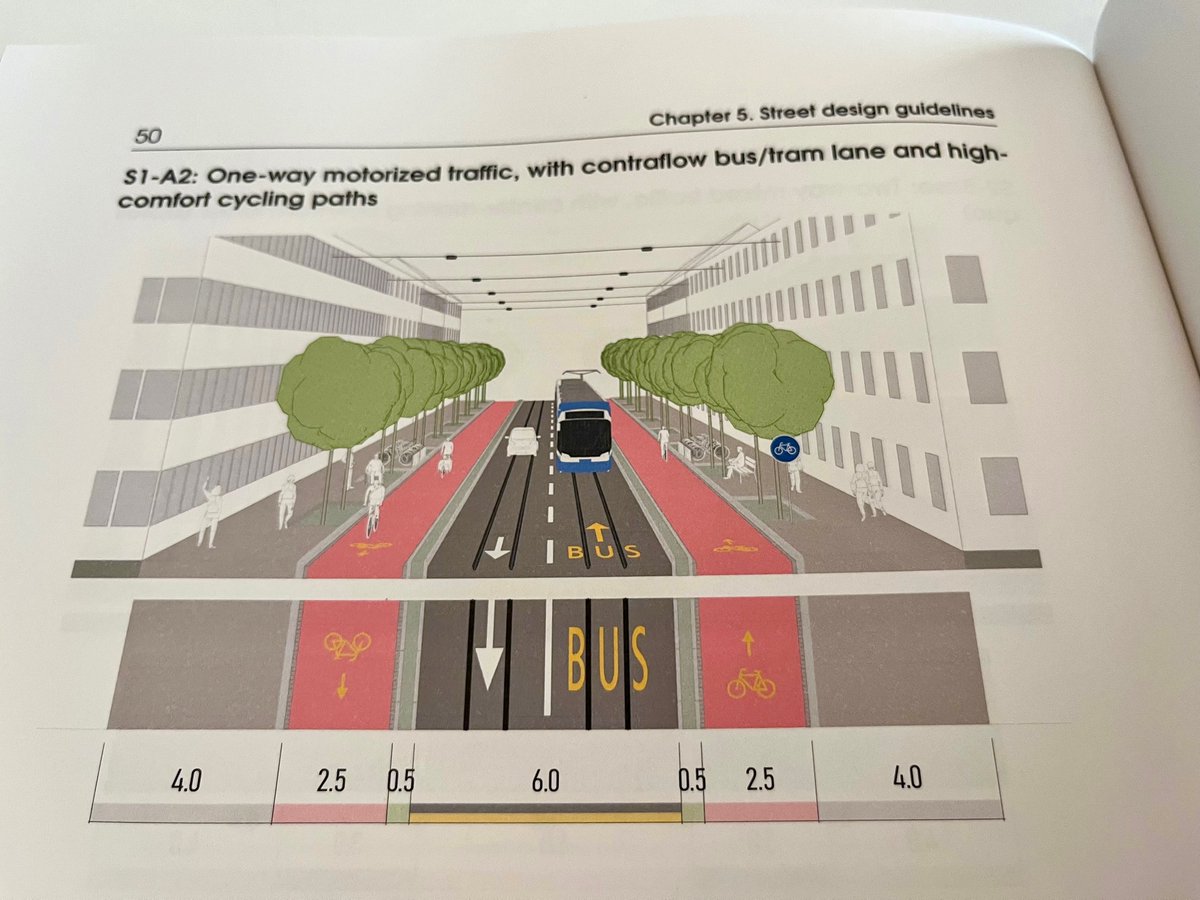

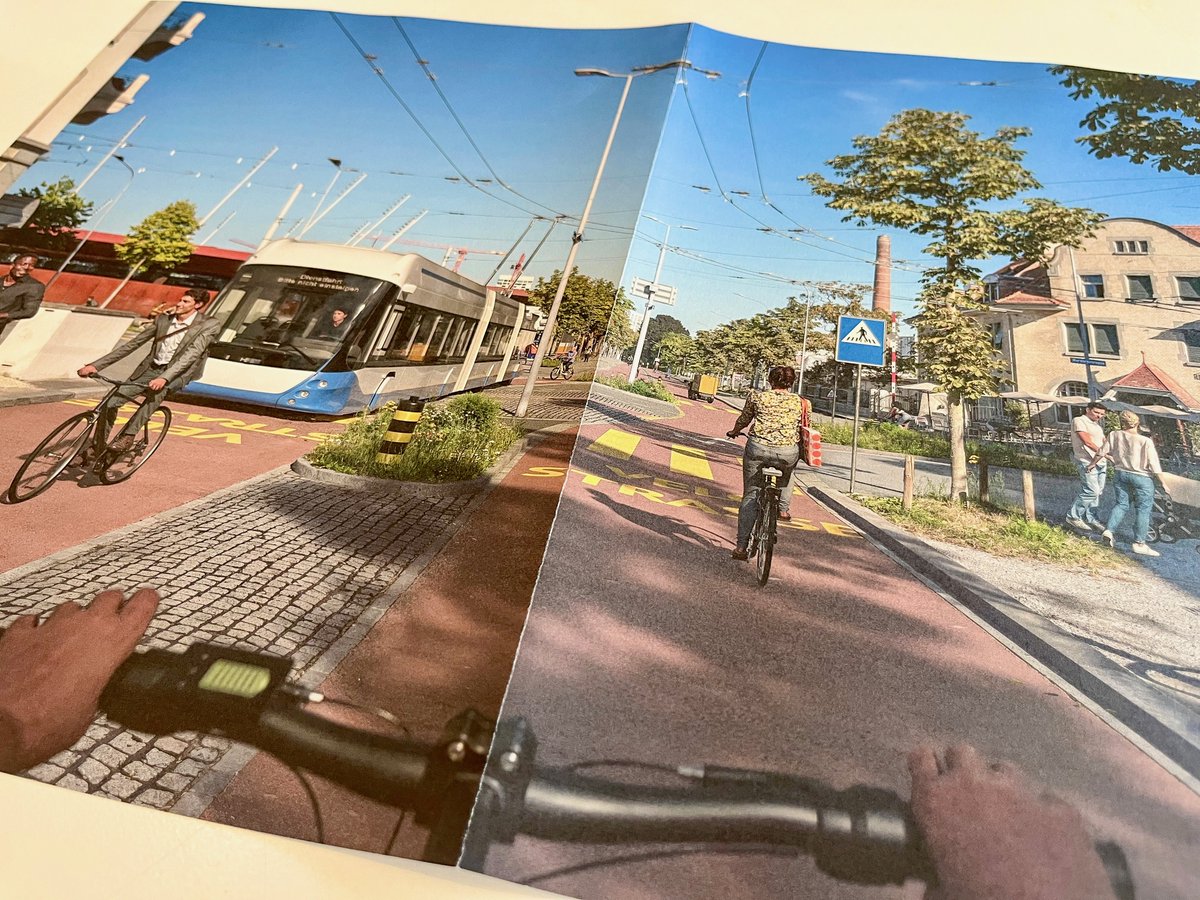

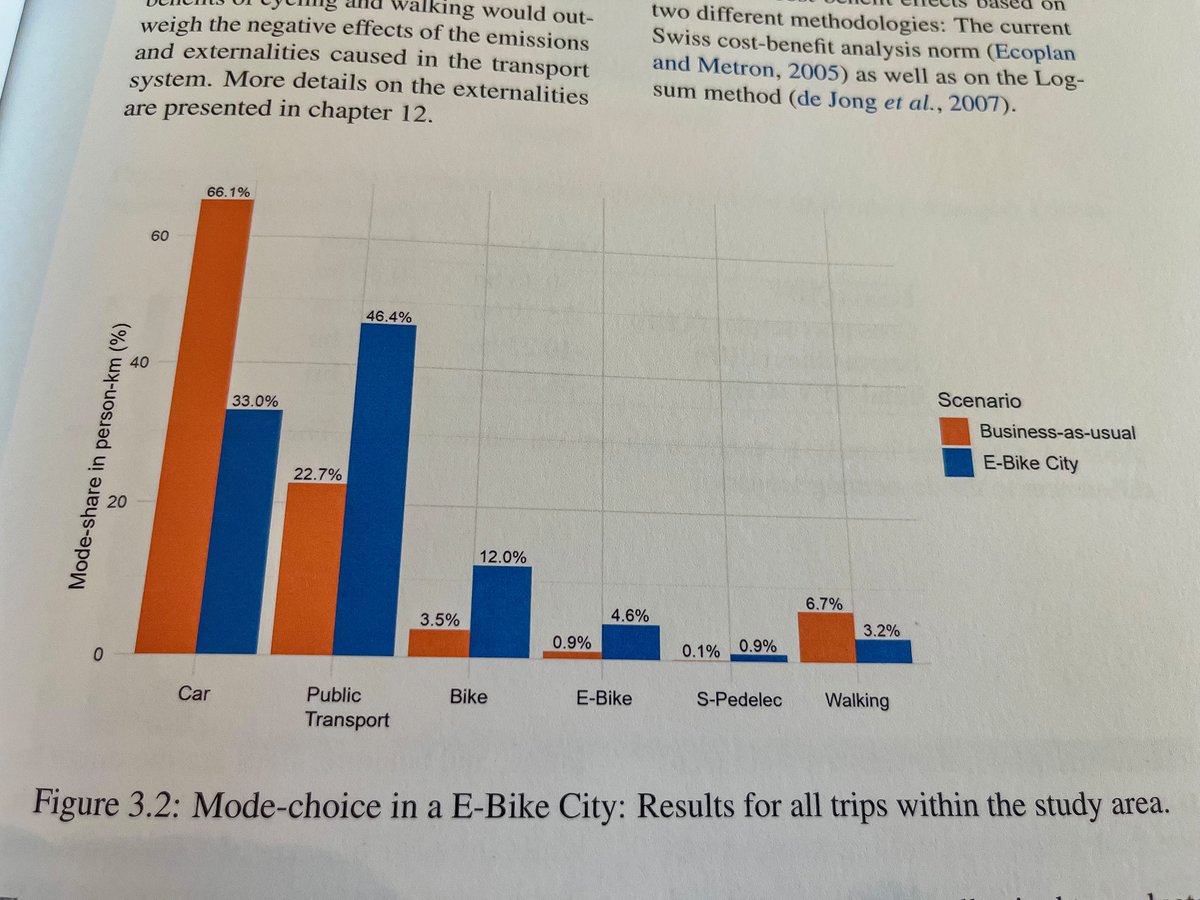

Today, 80% of Zurich’s road space is dedicated to cars and parking, while 10% serves (e-)cyclists. This project proposes reallocating half of all road space into safe, seamless routes for pedal-power and pedestrians, elevating quality-of-life while cutting emissions & collisions.

Today, 80% of Zurich’s road space is dedicated to cars and parking, while 10% serves (e-)cyclists. This project proposes reallocating half of all road space into safe, seamless routes for pedal-power and pedestrians, elevating quality-of-life while cutting emissions & collisions.

The quantitative effects were monitored before and after its implementation, focusing on six topics: 1️⃣ Road safety: On the 30 km/h roads, there were 11% fewer crashes involving a car, 15% fewer crashes involving a pedestrian/cyclist and 24% fewer crashes involving a tram or bus.

The quantitative effects were monitored before and after its implementation, focusing on six topics: 1️⃣ Road safety: On the 30 km/h roads, there were 11% fewer crashes involving a car, 15% fewer crashes involving a pedestrian/cyclist and 24% fewer crashes involving a tram or bus.

With 40% of motor traffic in its centre merely passing through, inspired by Groningen, Ghent's road system was restructured overnight. By changing flow on 80 streets, the city was divided into six zones, with direct car travel banned between them; forcing drivers around instead.

With 40% of motor traffic in its centre merely passing through, inspired by Groningen, Ghent's road system was restructured overnight. By changing flow on 80 streets, the city was divided into six zones, with direct car travel banned between them; forcing drivers around instead.

The unloved, inhospitable junction hegemonized by traffic was first subject to a temporary reallocation of space as part of Paris' "coronapistes". From there, a public consultation was started by the city in autumn 2021, which proposed replacing hard surface with dense woodland.

The unloved, inhospitable junction hegemonized by traffic was first subject to a temporary reallocation of space as part of Paris' "coronapistes". From there, a public consultation was started by the city in autumn 2021, which proposed replacing hard surface with dense woodland.

Within one month in office, Lores pedestrianized 300,000 m2 of the city centre, filtered out through traffic, and removed significant amounts of on-street parking, as it was determined 60% of vehicles were circulating in search of a space—a significant contributor to congestion.

Within one month in office, Lores pedestrianized 300,000 m2 of the city centre, filtered out through traffic, and removed significant amounts of on-street parking, as it was determined 60% of vehicles were circulating in search of a space—a significant contributor to congestion.

Practically a copy-paste of the plan implemented in the Dutch city of Groningen in 1977, Vilnius' center is divided into four zones, each with one main entrance and one or two exits. Traffic in each loop is one-way only, regulated by signage, barriers, and a 20 km/hr speed limit.

Practically a copy-paste of the plan implemented in the Dutch city of Groningen in 1977, Vilnius' center is divided into four zones, each with one main entrance and one or two exits. Traffic in each loop is one-way only, regulated by signage, barriers, and a 20 km/hr speed limit.

The municipality is consulting residents on what they would like to see replace the 10 square metre parking places. Options include more trees and plants, vegetable allotments, composting areas, children’s playgrounds, bicycle parking areas, and public toilets, among many others.

The municipality is consulting residents on what they would like to see replace the 10 square metre parking places. Options include more trees and plants, vegetable allotments, composting areas, children’s playgrounds, bicycle parking areas, and public toilets, among many others.

It's first worth pointing out a car-only transport system is perhaps the most ableist of all. A third of the population does not have the physical or financial means to drive: like children, the elderly, caregivers, people with lower incomes, and those with physical disabilities.

It's first worth pointing out a car-only transport system is perhaps the most ableist of all. A third of the population does not have the physical or financial means to drive: like children, the elderly, caregivers, people with lower incomes, and those with physical disabilities.

Rather we should share our vision of a liveable future; sparking a values-based conversation on our aspirations, on which there’s a lot of consensus: on safety, health, greenery, equity, sustainability, prosperity. Once we agree on the destination, we can debate how to get there.

Rather we should share our vision of a liveable future; sparking a values-based conversation on our aspirations, on which there’s a lot of consensus: on safety, health, greenery, equity, sustainability, prosperity. Once we agree on the destination, we can debate how to get there.

While an F1 race is an unlikely place for a sustainable transport revolution, the event’s 110,000 daily attendees were prohibited from arriving by car.

While an F1 race is an unlikely place for a sustainable transport revolution, the event’s 110,000 daily attendees were prohibited from arriving by car.

1️⃣ The “right to mobility”: The law recognized mobility as a fundamental right of residents. It prioritized including citizens in the network’s planning, regulation, and managing processes; incorporating principles of urban resilience, inclusive governance, and active transport.

1️⃣ The “right to mobility”: The law recognized mobility as a fundamental right of residents. It prioritized including citizens in the network’s planning, regulation, and managing processes; incorporating principles of urban resilience, inclusive governance, and active transport.

1️⃣ Proximity to Platform: The thing that cyclists making their way to the train want above all is a logical approach route and the ability to park their bikes as close to the platform as possible. Their walk from the parking space to the platform should be less than four minutes.

1️⃣ Proximity to Platform: The thing that cyclists making their way to the train want above all is a logical approach route and the ability to park their bikes as close to the platform as possible. Their walk from the parking space to the platform should be less than four minutes.

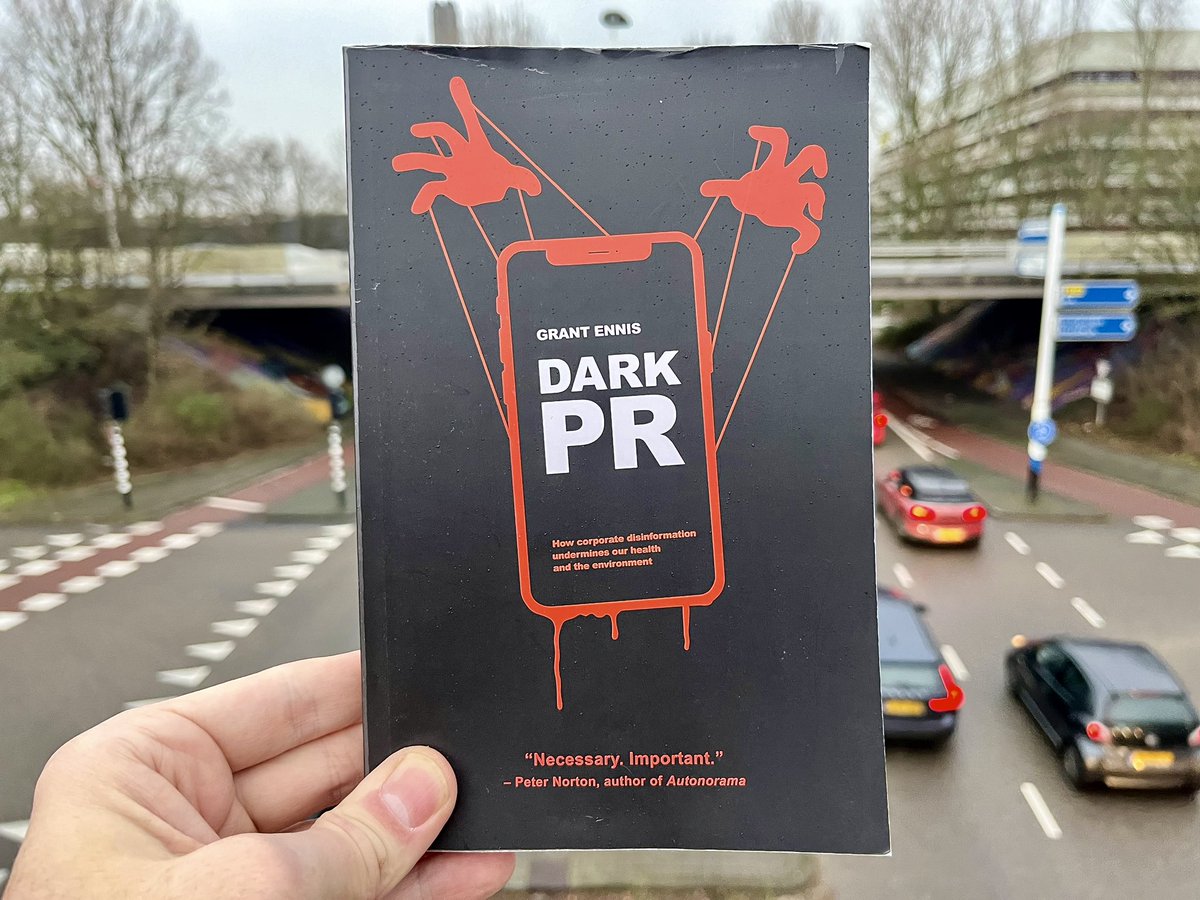

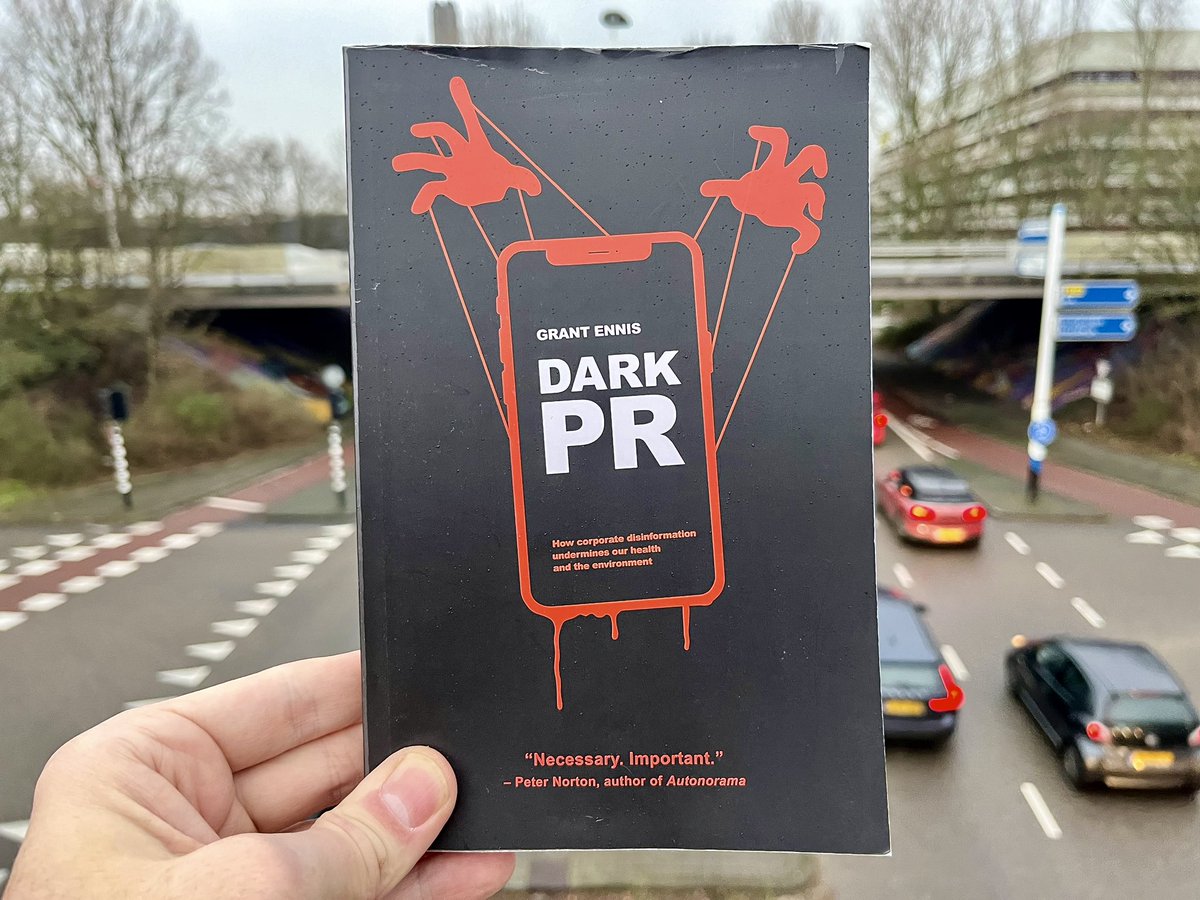

1. Denialism: “The road lobby’s most pervasive denialist framing is speed does not kill, or high speeds can be made safe under the right conditions. Nothing could be further from the truth… a change in average speed on a road network is directly related to the fatal crash rate.”

1. Denialism: “The road lobby’s most pervasive denialist framing is speed does not kill, or high speeds can be made safe under the right conditions. Nothing could be further from the truth… a change in average speed on a road network is directly related to the fatal crash rate.”