I have a pretty major update for one of my articles.

It has to do with Justice Jackson's comment that when Black newborns are delivered by Black doctors, they're much more likely to survive, justifying racially discriminatory admissions.

We now know she was wrong🧵

It has to do with Justice Jackson's comment that when Black newborns are delivered by Black doctors, they're much more likely to survive, justifying racially discriminatory admissions.

We now know she was wrong🧵

So if you don't recall, here's how Justice Jackson described the original study's findings.

She was wrong to describe it this way, because she mixed up percentage points with percentages, and she's referring to the uncontrolled rather than the fully-controlled effect.

She was wrong to describe it this way, because she mixed up percentage points with percentages, and she's referring to the uncontrolled rather than the fully-controlled effect.

After I saw her mention this, I looked into the study and found that its results all seemed to have p-values between 0.10 and 0.01.

Or in other words, the study was p-hacked.

Or in other words, the study was p-hacked.

If you look across all of the paper's models, you see that all the results are borderline significant at best, and usually just-nonsignificant, which is a sign of methodological tomfoolery and results that are likely fragile.

With all that said, I recommended ignoring the paper.

With all that said, I recommended ignoring the paper.

Today, a reanalysis has come out, and it doesn't tell us why the coefficients are all at best marginally significant, but instead, why they're all in the same direction.

The reason has to do with baby birthweights.

The reason has to do with baby birthweights.

So, first thing:

(A) At very low birthweights, babies have higher mortality rates, and they're similar across baby races;

(B) At very low birthweights, babies have higher mortality rates, and they're similar across physician races.

(A) At very low birthweights, babies have higher mortality rates, and they're similar across baby races;

(B) At very low birthweights, babies have higher mortality rates, and they're similar across physician races.

Second thing: Black infants tend to have lower birthweights.

MIxed infants tend to birthweights in-between Blacks and Whites, and there's a mother effect, such that Black mothers have smaller mixed babies than White mothers (selection is still possible)

MIxed infants tend to birthweights in-between Blacks and Whites, and there's a mother effect, such that Black mothers have smaller mixed babies than White mothers (selection is still possible)

https://x.com/cremieuxrecueil/status/1648579922279923712

Third thing:

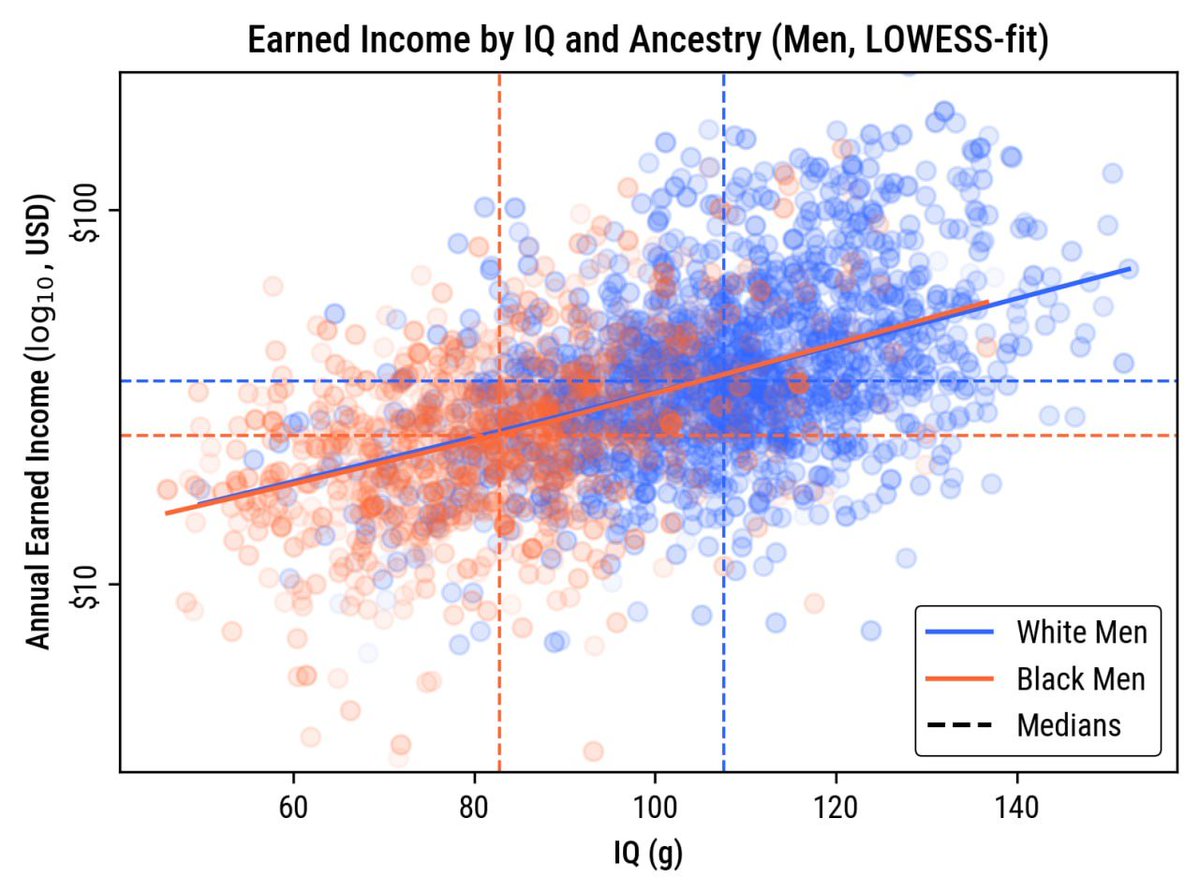

(A) Black babies with high birthweights disproportionately go to Black doctors;

(B) The Black babies sent to White doctors disproportionately have very low birthweights.

(A) Black babies with high birthweights disproportionately go to Black doctors;

(B) The Black babies sent to White doctors disproportionately have very low birthweights.

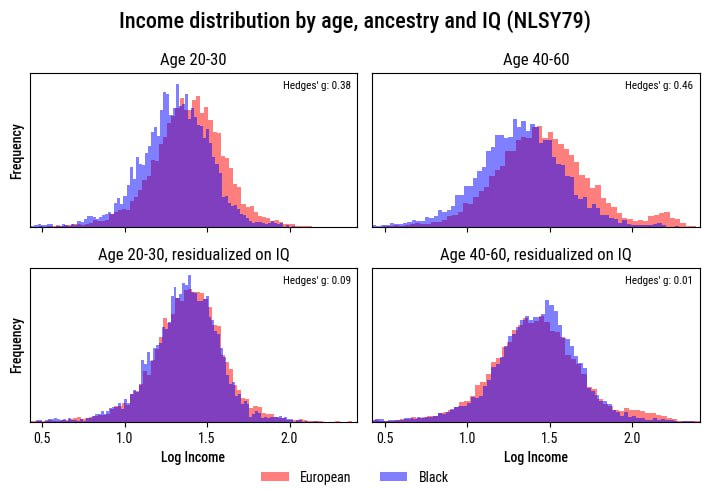

If you control for birthweight when running the original authors' models, two things happen.

For one, they fit a lot better.

For two, the apparently beneficial effect of patient-doctor racial concordance for Black babies disappears:

For one, they fit a lot better.

For two, the apparently beneficial effect of patient-doctor racial concordance for Black babies disappears:

At this point, we have to ask ourselves why the original study didn't control for birthweight. One sentence in the original paper suggests the authors knew it was a potential issue, but they still failed to control for it.

PNAS also played an important role in keeping the public misinformed because they didn't mandate that the paper include its specification, so no one could see if birthweight was controlled. If we had known the full model details, surely someone would have called this out earlier.

Ultimately, we have ourselves yet another case of PNAS publishing highly popular rubbish and it taking far too long to get it corrected.

Let me preregister something else:

The original paper will continue to be cited more than the correction with the birthweight control.

Let me preregister something else:

The original paper will continue to be cited more than the correction with the birthweight control.

The public will continue to be misled by the original, bad result. PNAS should probably retract it for the good of the public, but if I had to bet, they won't.

So people like Justice Jackson will continue to cite it to support their case for racial discrimination.

So people like Justice Jackson will continue to cite it to support their case for racial discrimination.

They'll continue doing that even though they're wrong.

To learn more and to find the article linked, check out my post on this: cremieux.xyz/p/missing-fixe…

To learn more and to find the article linked, check out my post on this: cremieux.xyz/p/missing-fixe…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh