If you look in a printed muṣḥaf today, and you're familiar with modern Arabic orthography, you will immediately be struck that many of the word are spelled rather strangely, and not in line with the modern norms.

This is both an ancient and a very modern phenomenon. 🧵

This is both an ancient and a very modern phenomenon. 🧵

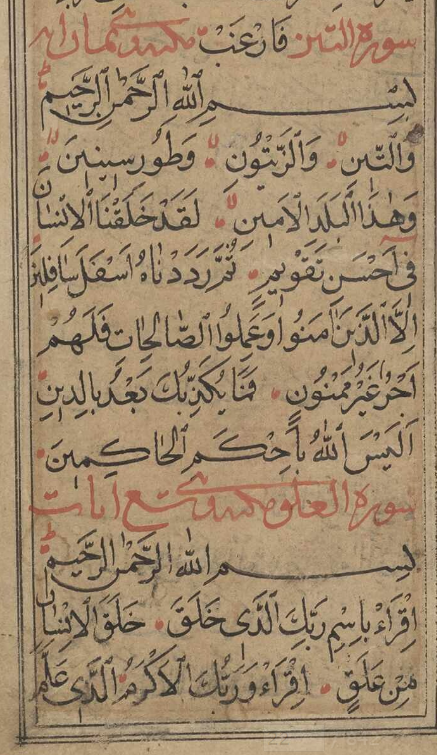

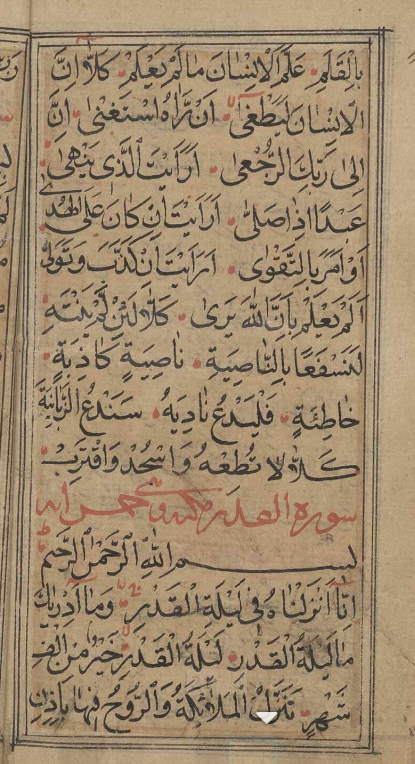

On the two page spread in the previous post alone there are 25 (if I didn't miss any) words that are not spelled the way we would "expect" them to.

The reason for this is because modern print editions today try to follow the Uthmanic rasm.

The reason for this is because modern print editions today try to follow the Uthmanic rasm.

During the third caliph Uthman's reign, in the middle of the 7th century, he established an official standard of the text. This text was written in the spelling norms of the time. This spelling is called the rasm.

But since that time the orthographic norms of Arabic changed.

But since that time the orthographic norms of Arabic changed.

For centuries, scribes would try to strictly adhere to the Uthmanic spelling when writing Quran. But when writing other texts, they would use their modern spelling norms.

Despite this conservatism, over the centuries some innovations did sneak into Muṣḥafs.

Despite this conservatism, over the centuries some innovations did sneak into Muṣḥafs.

For example, in the earliest 7th century manuscripts we have, the verb qāla "he said" is consistently spelled without ʾalif, i.e. قل, identically to qul "say!". But in later manuscripts, we see that ʾalifs have been added, even if the text otherwise closely follows the rasm.

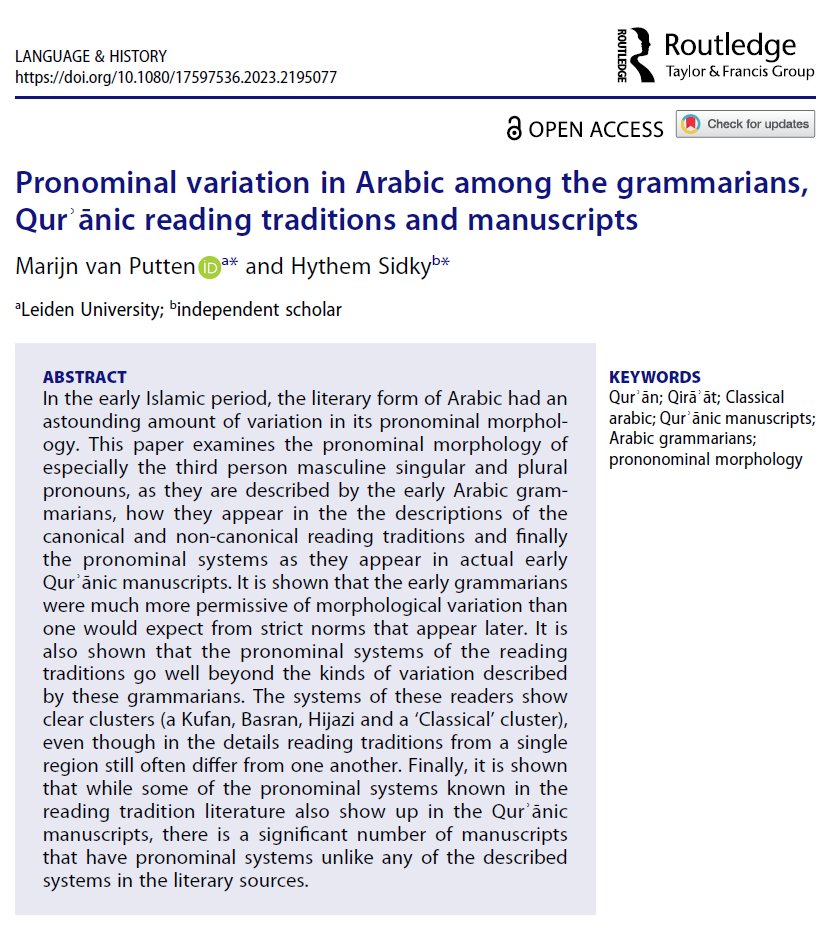

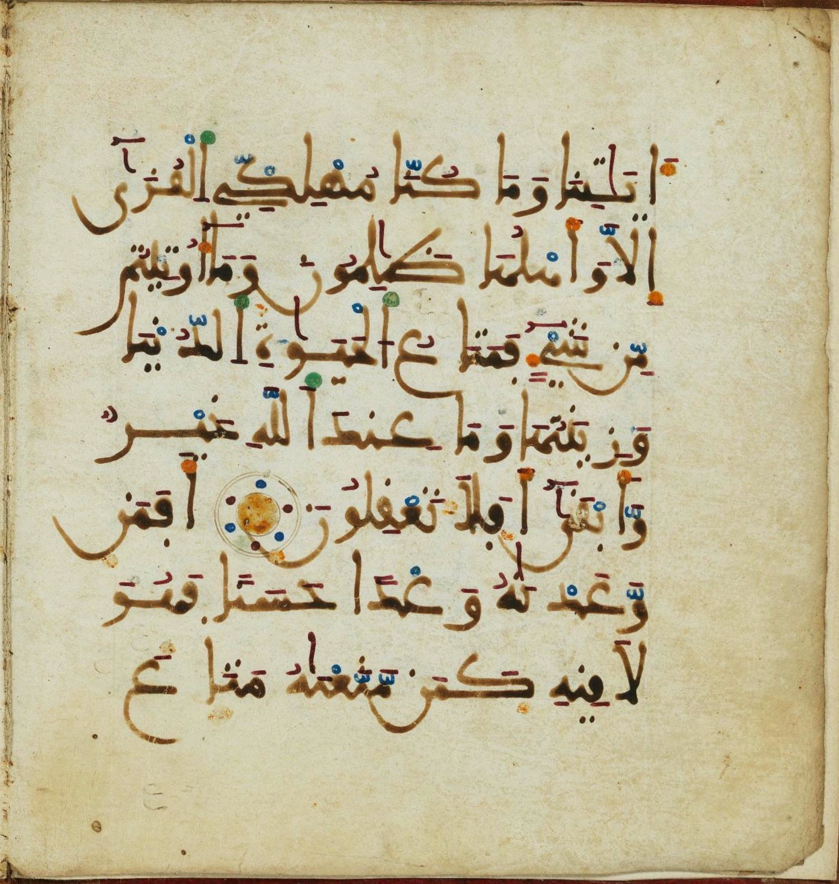

For example here in Q3:37, we see:

qāla yā-maryamu ʾannā laki hāḏā?

First in the 7th century Codex Parisino-Petropolitanus spelling qāla as ڡل.

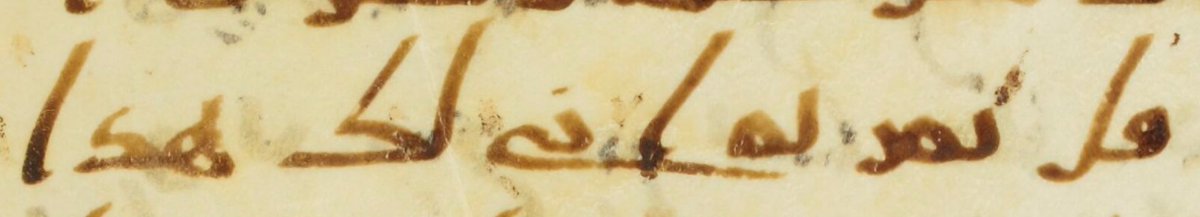

And in the 3rd/4th century manuscript Codex Amrensis 197, it is spelled ڡال.

qāla yā-maryamu ʾannā laki hāḏā?

First in the 7th century Codex Parisino-Petropolitanus spelling qāla as ڡل.

And in the 3rd/4th century manuscript Codex Amrensis 197, it is spelled ڡال.

While the rasm even in such later manuscripts is still very conservative and close to the original 7th century spelling, there are already hundreds of places where the spelling has changed somewhat.

While not fully successful, the intention was clearly to adhered to it.

While not fully successful, the intention was clearly to adhered to it.

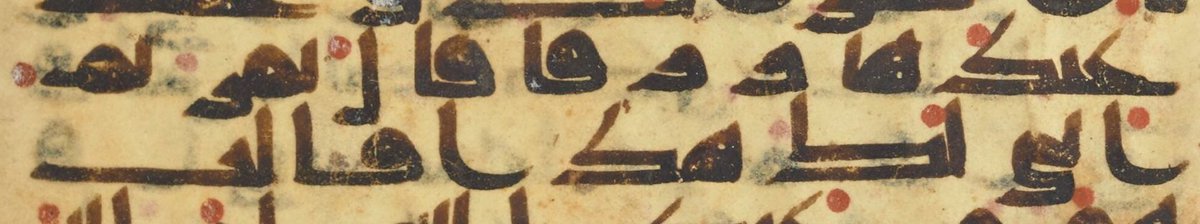

In the 5th/11th century orthographic norms of Arabic had become very different from that of the rasm. Scholars, especially in al-ʾAndalus, start becoming concerned with the preservation of the rasm, and start writing guides that explain the Uthmanic orthography.

These guides, such as ʾAbū ʿAmr al-Dānī's muqniʿ consist of long lists of orthographic idiosyncrasies of the Uthmanic text compared to the then current orthographic norms.

Modern print editions don't base themselves on the earliest manuscripts, but rather on such guides.

Modern print editions don't base themselves on the earliest manuscripts, but rather on such guides.

While these guides are valiant efforts to preserve the rasm, they fail to capture every single idiosyncrasy, and such guides did not necessarily have access to the very earliest manuscripts.

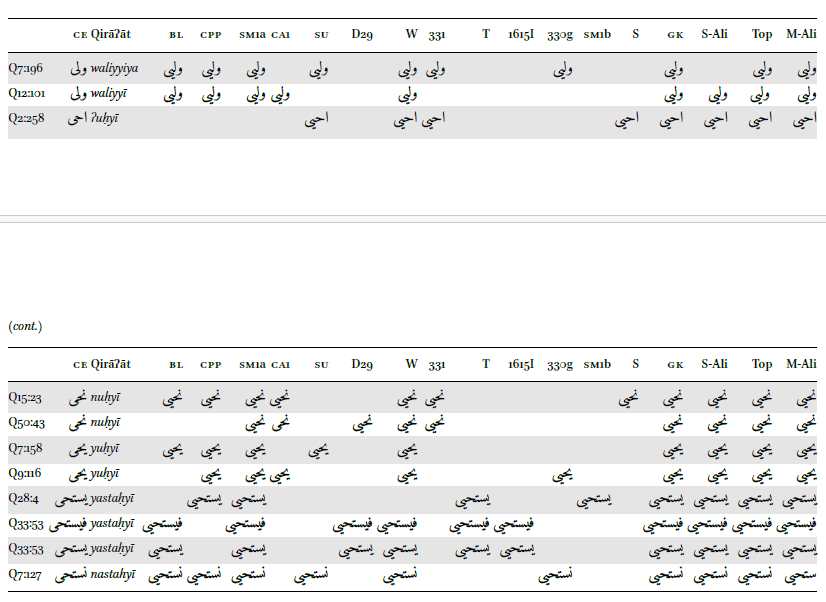

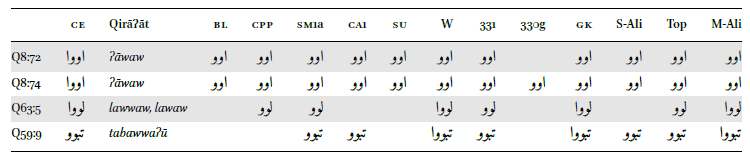

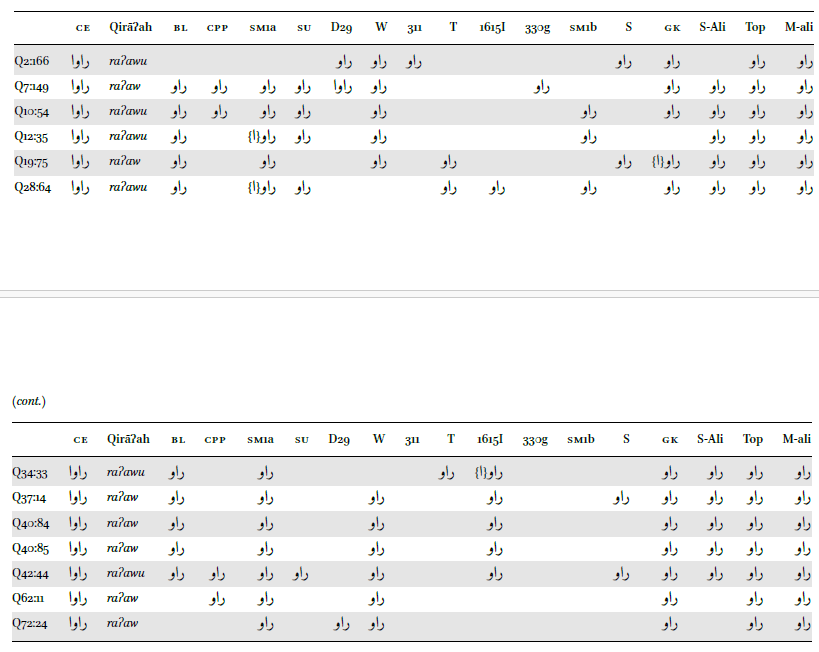

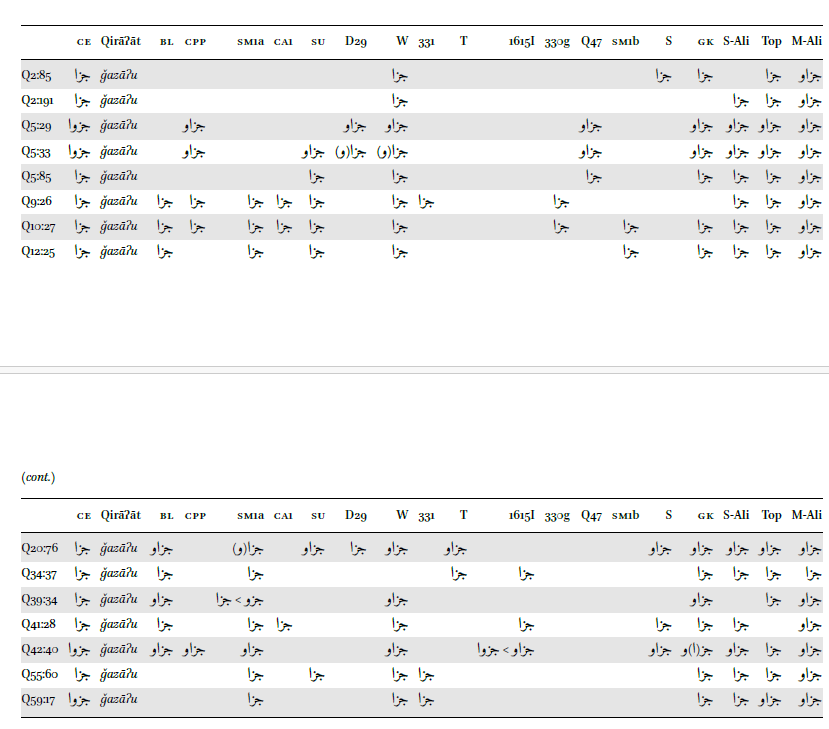

As a result, there are hundreds of places where the spelling prescribed by the rasm guides do *not* fit what we find in our earliest manuscripts. In Appendix B of my book I have many tables that showcase this phenomenon.

Surprisingly, the incorrectly prescribed spelling is not always in the direction of standard Classical Arabic spelling. For example yuḥyī should be spelled يحيي with two yāʾs, and that's what we find in *all* early manuscripts, but strangely al-Dānī prescribed يحي with one yāʾ.

It should also be noted that such rasm works do not present spellings with 100% certainty. Frequently there are competing opinions for such words. Also between different works there can be disagreement on the spelling of certain works.

This is why the Medinah quran tells us that it follows the works of ʾAbū ʿAmr al-Dānī and ʾAbū Dāwūd Sulaymān b. Naǧāḥ but that they give preference to the latter in the case if disagreement.

So while modern Muṣḥafs are a good approximation, they are not a perfect reflection of what Uthmān's original standard rasm looked like. Early manuscripts are obviously a better guide, but even there we are left with ambiguities.

The use of these rasm works to write Muṣḥafs became very popular in the Islamic west, and after al-Dānī basically all maghrebi manuscripts adopt the orthographic norms set by al-Dānī et al.

At the same time in the Islamic east, however, things look strikingly different! Here around the 11th century, when Muṣḥafs start to be written in forms of the Nasḫ script, the Uthmanic rasm is abandoned completely in favour of Classical orthography.

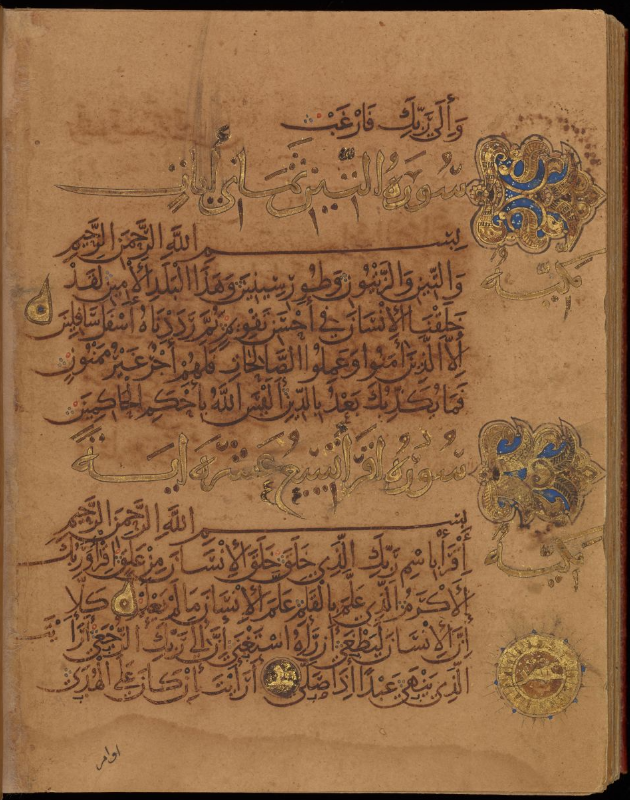

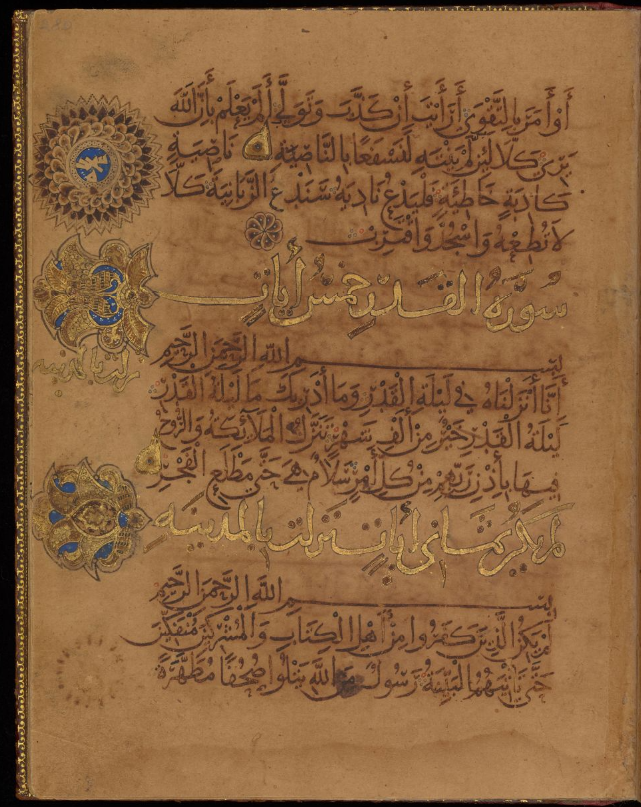

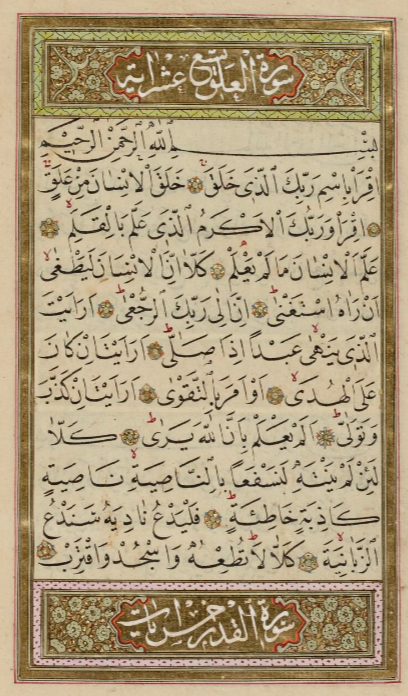

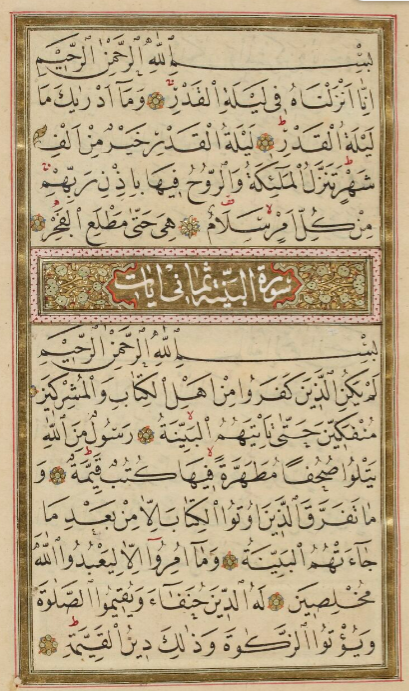

This is nicely exemplified by the Ibn al-Bawwāb Quran (391/1000). Note that the same section I started with thread with, virtually every time Ibn al-Bawwāb has the spelling that we would considered "Classical" today!

Q95:4, Q96:2,5,6 الانسان NOT الانسن

Q95:5 رددناه NOT رددنه

Q95:5 سافلين NOT سفلين

Q95:6 الصالحات NOT الصلحت

Q95:8 الحاكمين NOT الحكمين

Q96:9,11,13 ارايت NOT اريت

Q96:16 كاذبة NOT كذبة

Q97:1 انزلناه NOT انزلنه

Q97:4 الملايكة NOT المليكة

Q97:5 سلام NOT سلم

Q98:1,4 الكتاب NOT الكتب

Q95:5 رددناه NOT رددنه

Q95:5 سافلين NOT سفلين

Q95:6 الصالحات NOT الصلحت

Q95:8 الحاكمين NOT الحكمين

Q96:9,11,13 ارايت NOT اريت

Q96:16 كاذبة NOT كذبة

Q97:1 انزلناه NOT انزلنه

Q97:4 الملايكة NOT المليكة

Q97:5 سلام NOT سلم

Q98:1,4 الكتاب NOT الكتب

A number of non-Classical spellings remain (e.g. لنسفعا rather than لنسفعن and ادريك instead of ادراك), but the general trend is clear: the orthography has almost completely been adapted to the modern Classical Arabic orthography (and probably completely to the norms of its time)

The Ibn al-Bawwāb Quran is by no means the exception to the rule. This becomes the standard in the Islamic east. And this continues well into the Ottoman period. Even 20th century Ottoman Muṣḥafs mostly follow the standard Classical spelling rather than the rasm.

In terms of layout and script style, modern print editions like the Cairo Edition clearly draw from the Ottoman style of Muṣḥaf creation, the strict adherence to the Uthmanic rasm is in fact a very Maghrebi practice -- making modern print qurans unusual amalgamations.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh