Not trying to create a pile-on here. But let's talk about why something might still be made in unethical conditions even though it bears a "made in USA" tag. 🧵

The first thing to understand is that not all workers are covered by US labor laws. You might assume that workers get paid a minimum wage (after all, it says "minimum"). In fact, many garment workers in the US toil under what's known as the piecework system.

Piecework means you get paid not by the amount of time you work but the number of operations you complete. This system should be familiar to many of you. As a writer, I get paid per word. The pay is the same whether it takes me 100 or 10 hours to write a 1,000 word article.

My situation is fine bc I get paid enough to eat. But for a garment worker, the pay structure can be peanuts: three cents to sew a zipper or sleeve, five cents for a collar, and seven cents to prepare the top part of a skirt. These are real numbers for LA-based garment workers.

Piecework is how companies skirt minimum wage laws. Among labor organizers, the term "wage theft" refers to the difference between what a worker should have earned under min wage laws and what they actually earned through the piece rate system.

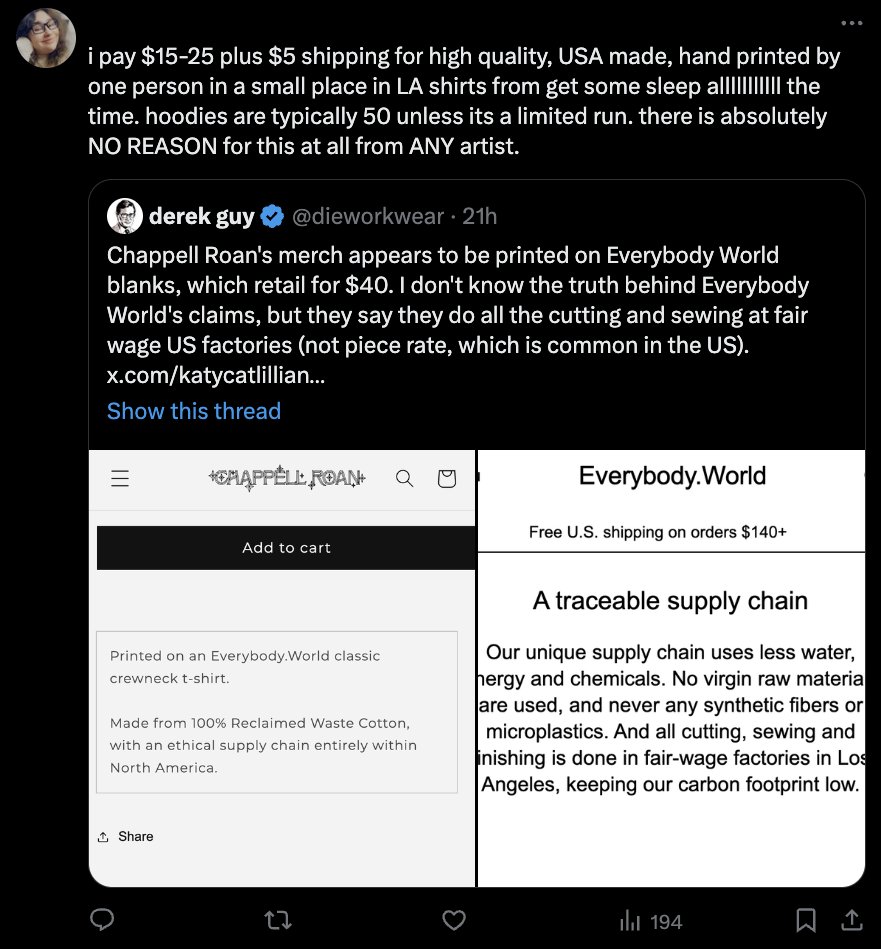

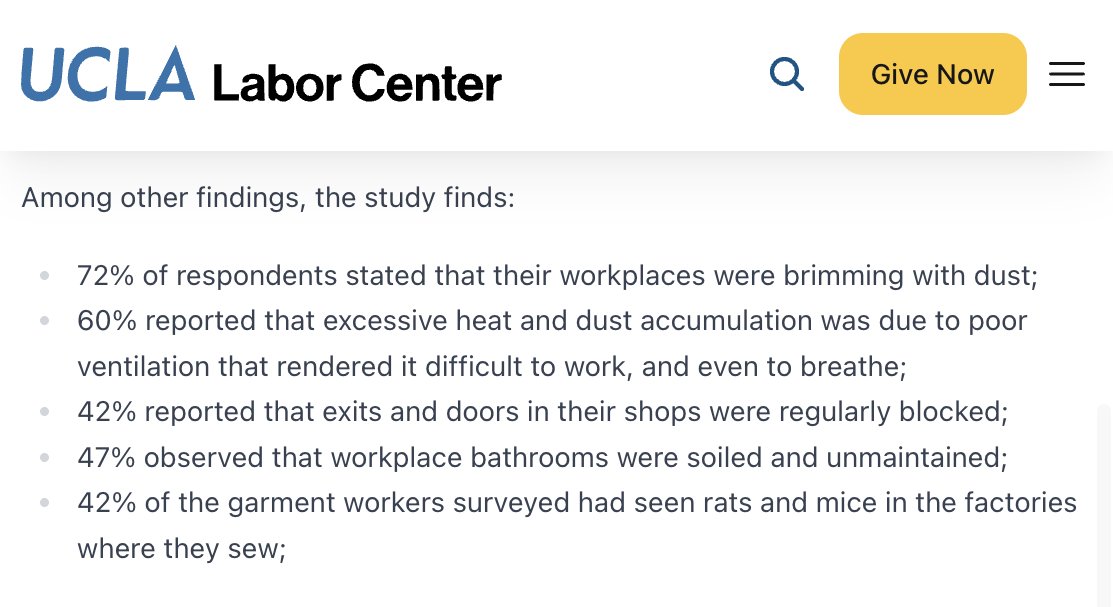

This system is incredibly common. A 2016 UCLA Labor Center study showed the median piece-rate worker in Los Angeles scrapes together $5.15 per hour—less than half the state’s mandated minimum wage. Labor conditions are also very bad: poor ventilation, dusty air, rats and mice.

A Federal Department of Labor investigation the same year found that 85 percent of Los Angeles garment factories were breaking labor laws. In 2016, these violations amounted to $1.3 million in back wages owed to 865 workers in a sample of 77 factories. This is wage theft.

In 2021, labor organizers won a fight to get piecework banned in California. But two years later, it's still incredibly common. I interviewed an LA-based garment worker who toils 12 hrs a day for $50. She sleeps in the corner of a kitchen. From my article in The Nation:

Currently, there's a new fight get piecework banned nationwide through the FABRC Act. I would link, but Twitter throttles threads that have outbound links, so I would prefer if you Google how you can support this legislation. Or follow @GarmentWorkerLA for more info.

The other reason why a "made in USA" tag may not mean much has to do with how the label is applied.

When you see this label inside your garment, what do you assume? Think about this before moving on to the next tweet.

When you see this label inside your garment, what do you assume? Think about this before moving on to the next tweet.

The Federal Trade Commission has pretty strict rules on who gets to apply that label. For clothes, the item has to be cut and sewn in the US using materials that were made in the US. The FTC tries to match its rules with the common understanding of what "made in US" means.

If you're a giant company like Levi's or LL Bean, you may have lawyers who are advising you on these rules. This is why you see labels like "imported," which means the item was made abroad. Or "made in the US from imported materials" when they can't meet the MiUSA standard.

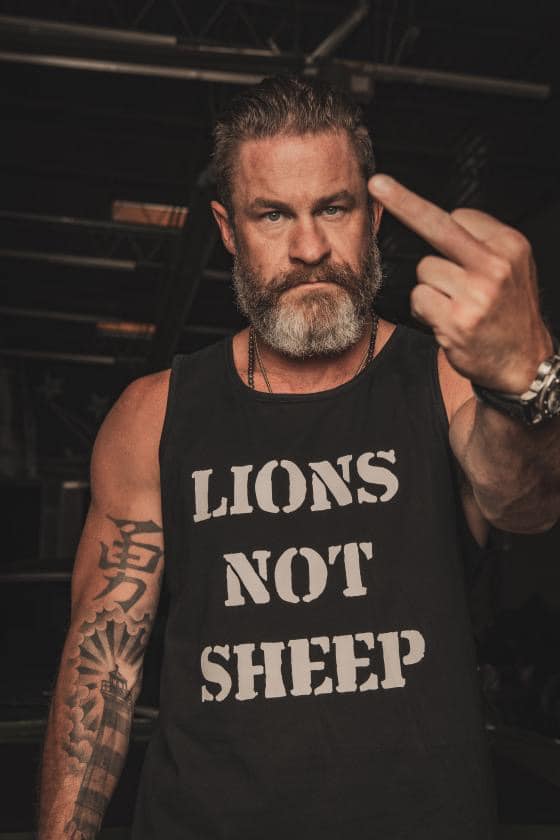

But it's incredibly common for companies to violate FTC rules. In 2022, the FTC fined the pro-Trump brand Lions Not Sheep $211k for labeling their t-shirts "made in USA" when the shirts were actually imported from China and other countries.

The company was basically importing blanks from China, ripping out the "made in China" label, screen printing the shirt in the US, and then applying a new screen-printed "made in US" label. CEO Sean Whalen claimed he was being persecuted for his pro-Trump views.

But the whole thing started bc Whalen made a video about how his customers are price sensitive, so he imports blanks from China. That's what kicked off the FTC investigation. So while this mislabeling is common, it's hard to get caught unless you make a video about your crimes.

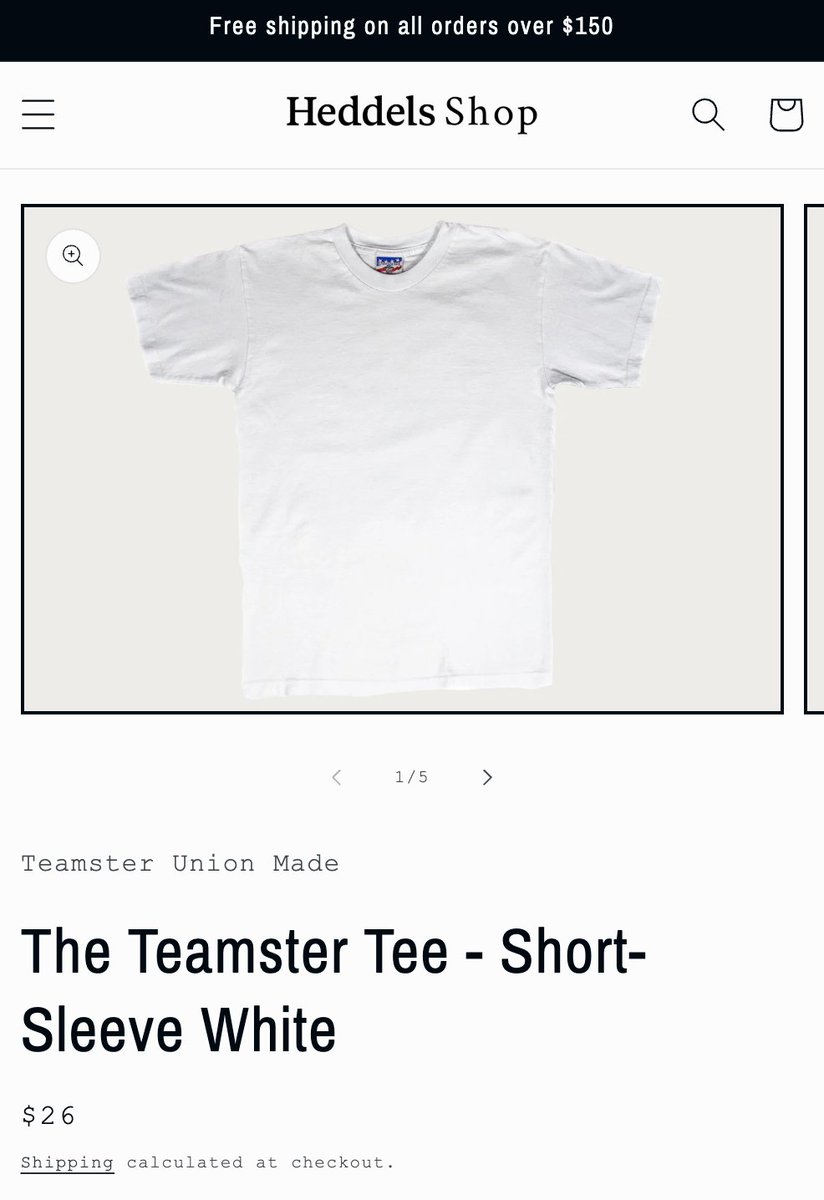

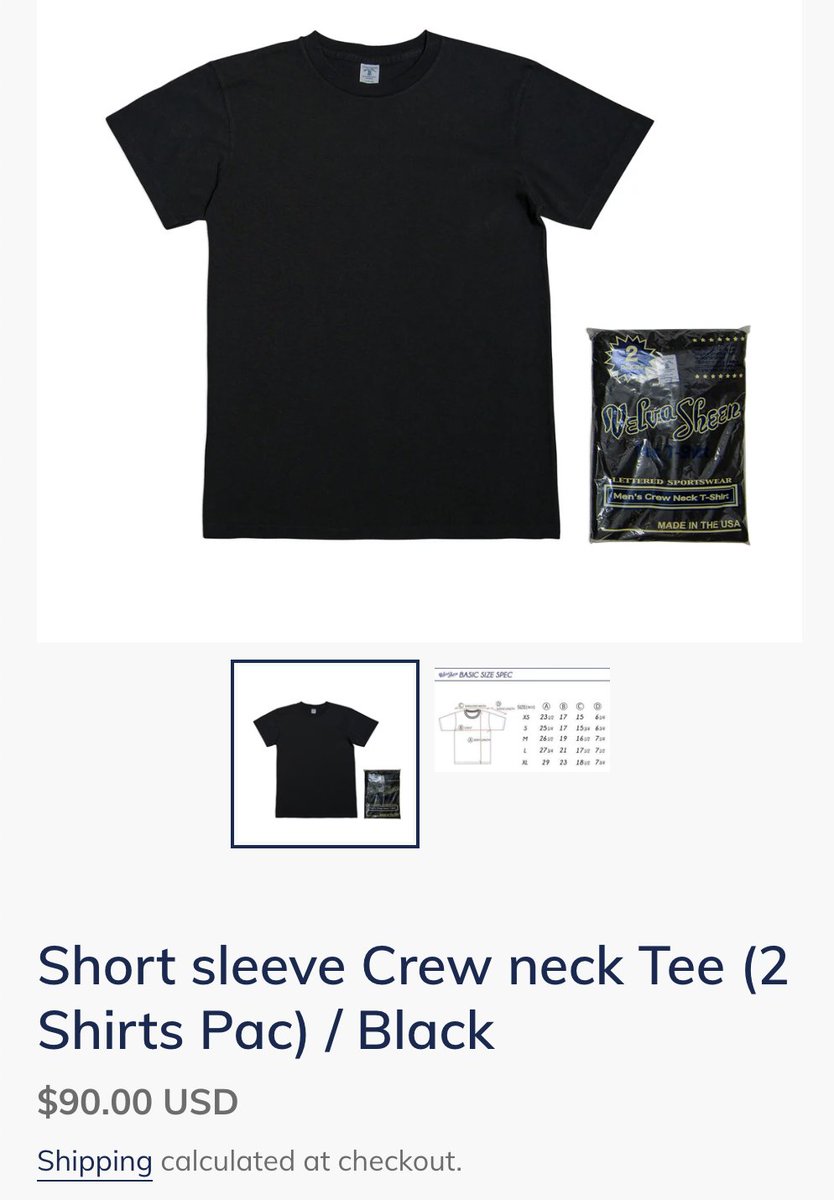

The truth is that making a t-shirt in the USA according to FTC standards will result in a relatively expensive garment. Heddels and Velva Sheen both produce shirts in the US from US grown cotton. The first is $26; second is $90 for a two-pack.

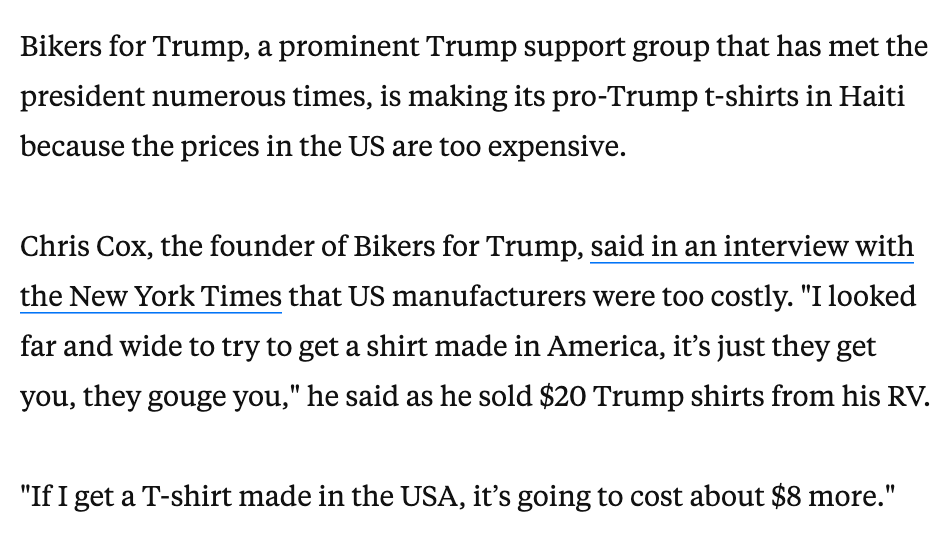

Once you add things such as screenprinting—or if you want a more unique cut and not just basic blanks—the costs go up. This is why Bikers for Trump sourced their merch from Haiti. They knew their customers would not pay an extra $8 for true made-in-USA production.

Today, there are countless companies that make merch for other organizations. They source their t-shirts from a variety of places—some made in the US, most not—and then screenprint a design and fulfill orders. This way, the other org doesn't have to do any work but marketing.

When you see a screenprinted t-shirt for $20, ask yourself: Where was the material grown? Where were the yarns spun? Where was the cutting, sewing, and finishing performed? Where was the screenprinted done? What were the wages and labor conditions along these steps?

I'm not a nationalist, so I don't prioritize American jobs over foreign ones. But I do care about fair wages and labor protections. Just because something was made abroad doesn't mean it was made in a sweatshop. Just because it was made in the US doesn't mean fair wages.

Paying more for a garment is also no guarantee of ethical manufacturing. But when the price of a garment is so low, you leave little on the table for workers. Just because you see a $20 t-shirt that says "made in USA" doesn't mean it was made fairly.

Please don't harass the person who posted that original tweet. My intention is not to cause harm or stress for anyone. Only to help shed light on what goes into garment manufacturing, fair labor, and labeling. Hopefully, you will consider these issues when shopping.

For the inevitable question: "How do I make sure my clothes were made ethically?" This is very difficult to answer in a thread. My simplest answer is that we should elect pro-worker politicians, fight for pro-labor laws, and empower unions so workers can advocate for themselves.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh