Let me celebrate today's Nobel Prize for Acemoglu, Robinson, and Johnson by summarising the work of the first two laureates on the relationship between inequality and democratisation. In fact, AR kicked off the literature on redistributive theories of democratisation. 1/n

Most summaries will focus on their contributions to the historical political economy of development, but their work on democratisation shouldn't go unmentioned today.

The synthesis of their work is presented in AR's "Economic Origins" book -- the

2/ncambridge.org/core/books/eco…

The synthesis of their work is presented in AR's "Economic Origins" book -- the

2/ncambridge.org/core/books/eco…

title of which is a play on Barrington Moore's famous work.

The key thesis of the book was aptly summarised by @SLMazzuca as "no revolutionary threat, no democracy".

How do they arrive at this conclusion? The answer can be found in chapter 2. Let's start with their ..

3/n

The key thesis of the book was aptly summarised by @SLMazzuca as "no revolutionary threat, no democracy".

How do they arrive at this conclusion? The answer can be found in chapter 2. Let's start with their ..

3/n

assumptions.

· Society is divided into two groups: elites and citizens, with the latter being more numerous than the former

· Distinction between democracy and non-democracy:

➡️ Democracy is defined as free and fair elections being in place. The defining feature of

4/n

· Society is divided into two groups: elites and citizens, with the latter being more numerous than the former

· Distinction between democracy and non-democracy:

➡️ Democracy is defined as free and fair elections being in place. The defining feature of

4/n

democracy is political equality.

· Because of political equality, democracy serves the preferences of the majority, which, by the preceding assumptions, are the citizens.

· If citizens are poorer than elite, then citizens will want redistribution, which democracy will

5/n

· Because of political equality, democracy serves the preferences of the majority, which, by the preceding assumptions, are the citizens.

· If citizens are poorer than elite, then citizens will want redistribution, which democracy will

5/n

therefore give rise to.

· By the Meltzer-Richard logic, the demand for redistribution will increase as inequality increases, i.e. as the difference between citizens’ income and the mean income rises.

I summarised the Meltzer-Richard logic here.

6/n

· By the Meltzer-Richard logic, the demand for redistribution will increase as inequality increases, i.e. as the difference between citizens’ income and the mean income rises.

I summarised the Meltzer-Richard logic here.

6/n

https://x.com/edenhofer_jacob/status/1825935225140162634

· Non-democracies serve the elite's interests.

· If the elite is wealthy and less numerous than the masses then non-democracies will redistribute less than democracies.

· Behavioural assumption: Individuals have well-defined preferences over the outcomes of their actions.

7/n

· If the elite is wealthy and less numerous than the masses then non-democracies will redistribute less than democracies.

· Behavioural assumption: Individuals have well-defined preferences over the outcomes of their actions.

7/n

· Implication: To work out what political systems individuals prefer, we can focus on the consequences these systems engender, especially their redistributive consequences.

· Conception of politics: politics is inherently conflictual and how these conflicts are resolved

8/n

· Conception of politics: politics is inherently conflictual and how these conflicts are resolved

8/n

depends on the balance of political power between the elites and citizens

· When the elite dominates, societal conflicts will be resolved in its favour and vice versa.

· Conception of political power:

· Two components: de jure and de facto political power

· Determinant of de

9/n

· When the elite dominates, societal conflicts will be resolved in its favour and vice versa.

· Conception of political power:

· Two components: de jure and de facto political power

· Determinant of de

9/n

jure political power are political institutions:

· “social and political arrangements that allocate de jure political power” (p. 21)

· Determinants of de facto political power more varied

· Citizens will have more political power under democracy than under non-democracy, 10/n

· “social and political arrangements that allocate de jure political power” (p. 21)

· Determinants of de facto political power more varied

· Citizens will have more political power under democracy than under non-democracy, 10/n

and will, thus, prefer the former to the latter; for elites, the reverse is true.

➡️Theory of democratisation

· “the citizens want democracy and the elites want nondemocracy, and the balance of political power between the two groups determines whether the society transits 11/n

➡️Theory of democratisation

· “the citizens want democracy and the elites want nondemocracy, and the balance of political power between the two groups determines whether the society transits 11/n

from nondemocracy to democracy” (p. 23)

· This simple theory neglects an important aspect: Why would citizens ever push for democracy if the balance of power favoured them in a non-democratic situation?

· Answer: Because the balance of power may change in the elite’s favour 12/n

· This simple theory neglects an important aspect: Why would citizens ever push for democracy if the balance of power favoured them in a non-democratic situation?

· Answer: Because the balance of power may change in the elite’s favour 12/n

over time, in which case the citizens would have no way of ensuring their interests are served in a non-democratic regime. Hence, they push for democracy to consolidate their current advantage to insure against potential declines in power in the future.

· Put differently: .. 13/n

· Put differently: .. 13/n

Citizens use their current de facto power to increase their future de jure power by pushing for democratisation.

· Key driver of citizens’ demands for democratisation: transitory nature of de facto power

· “It is precisely the transitory nature of political power – that .. 14/n

· Key driver of citizens’ demands for democratisation: transitory nature of de facto power

· “It is precisely the transitory nature of political power – that .. 14/n

the citizens have it today and may not have it tomorrow – that creates a demand for change in political institutions. The citizens would like to lock in the political power they have today by changing political institutions – specifically, by introducing ... 15/n

democracy and greater representation for themselves - because without institutional changes, their power today is unlikely to persist.” (p. 25)

· In nondemocracies, citizens’ de facto political power is determined by their ability to pose a (credible) revolutionary threat. 16/n

· In nondemocracies, citizens’ de facto political power is determined by their ability to pose a (credible) revolutionary threat. 16/n

· Note: This means they have to solve a collective action problem.

· When will the elite concede the citizens’ demand for democratisation? Can’t the elite prevent democratisation by making concessions to citizens while retaining the nondemocratic framework?

· Answer to first 17/n

· When will the elite concede the citizens’ demand for democratisation? Can’t the elite prevent democratisation by making concessions to citizens while retaining the nondemocratic framework?

· Answer to first 17/n

question: When the costs, in terms of the increase in redistribution entailed by democratisation and the repression necessary to neutralise the revolutionary threat, are not excessively high.

· Answer to second question: No, because the elite cannot credibly promise to 18/n

· Answer to second question: No, because the elite cannot credibly promise to 18/n

citizens that it will increase redistribution (provide more public goods, etc.) in nondemocracies. Once the balance of power has shifted in elite’s favour, they have an incentive to renege on the promises they made when their relative de facto power was low.

· The elite ... 19/n

· The elite ... 19/n

faces a commitment problem, entailing that it cannot prevent democratisation by making concessions in the non-democratic framework.

· “A credible promise (…) means that it has to change the future allocation of political power. That is precisely what a transition to .. 20/n

· “A credible promise (…) means that it has to change the future allocation of political power. That is precisely what a transition to .. 20/n

democracy does: it shifts political power away from the elite to the citizens, thereby creating a credible commitment to future pro-majority policies. The role that political institutions play in allocation power and leading to relatively credible commitments is the third .. 21/n

key building block of our approach.” (p. 26)

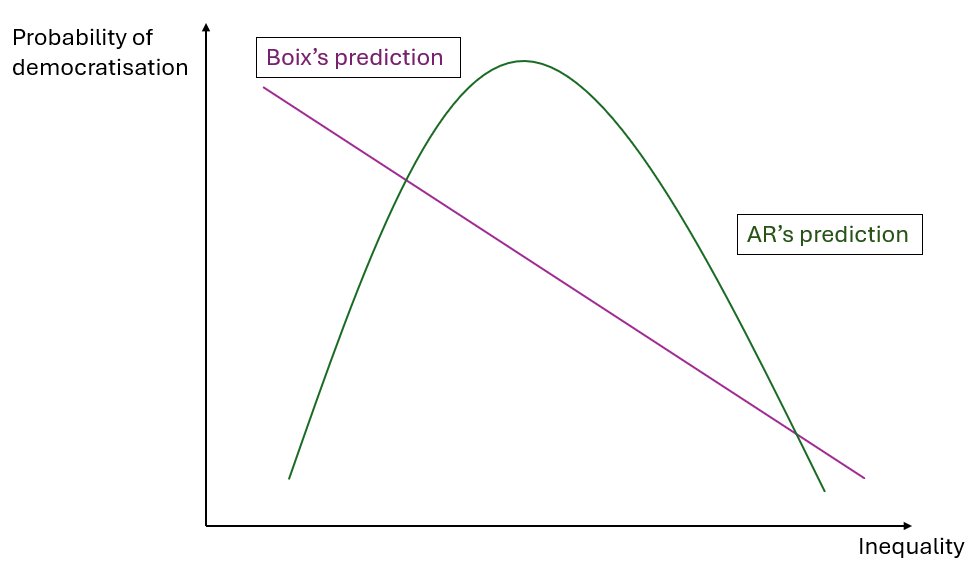

Their comparative statics is pretty rich, but I'll focus on the the inequality-related ones and contrast it with the very important contribution by @boixserra. He relied on the Meltzer-Richard logic

22/ncambridge.org/core/books/dem…

Their comparative statics is pretty rich, but I'll focus on the the inequality-related ones and contrast it with the very important contribution by @boixserra. He relied on the Meltzer-Richard logic

22/ncambridge.org/core/books/dem…

which implies that the redistributive threat of democratisation rises as inequality increases. As a result, the elite's willingness to engage in repression increases with inequality, implying that the probability of democratisation declines monotonically in inequality. 23/n

This ignores the mobility-related part of Boix's argument, of course. But AR argue the relationship between the prob. of democratisation and inequality follows an inverted U-shape (see 👇). Why?

Because 🔼inequality has two countervailing effects:

· greater redistributive 24/n

Because 🔼inequality has two countervailing effects:

· greater redistributive 24/n

burden for elites in democracy (by Meltzer-Richard logic)

· makes repression more attractive for elites, thereby discouraging democratisation

Therefore:

· In equal autocratic societies, revolution is not sufficiently attractive for citizens; there is no democratisation. 25/n

· makes repression more attractive for elites, thereby discouraging democratisation

Therefore:

· In equal autocratic societies, revolution is not sufficiently attractive for citizens; there is no democratisation. 25/n

The empirics in AR is mostly qualitative and anecdotal, but their theoretical contribution succeeded in setting the agenda for much of the study of democratisation.

Let me illustrate this by summarising some of the central contributions that take AR as their point of

26/n

Let me illustrate this by summarising some of the central contributions that take AR as their point of

26/n

departure.

1. @benwansell and @Samuels_DavidJ seminal book

Their key message: it is intra-elite competition - especially the fear of economically rising, but politically disenfranchised elites - that drives democratisation and this type of

27/ncambridge.org/core/books/ine…

1. @benwansell and @Samuels_DavidJ seminal book

Their key message: it is intra-elite competition - especially the fear of economically rising, but politically disenfranchised elites - that drives democratisation and this type of

27/ncambridge.org/core/books/ine…

competition is most likely to exist when land inequality is low and income inequality high.

· The driver of democratisation is the fear of politically disenfranchised, but economically rising elites to be expropriated by incumbent elites.

To arrive at this conclusion, they

28/n

· The driver of democratisation is the fear of politically disenfranchised, but economically rising elites to be expropriated by incumbent elites.

To arrive at this conclusion, they

28/n

consider a two-sector economy (industry vs land), which allows them to introduce two types of inequality -- income and land inequality. Below I reproduced one of their tables, which illustrates some historical examples can be understood in light of this distinction.

29/n

29/n

In developing their theory, they challenge four assumptions of conventional redistributive accounts.

1. Rather than thinking about a stagnant, one sector economy, they assume a two-sector economy, with one sector being relatively more important over time.

30/n

1. Rather than thinking about a stagnant, one sector economy, they assume a two-sector economy, with one sector being relatively more important over time.

30/n

2. Three, as opposed to two, groups: landed elite, industrial elite, and masses.

3. They allow for autocracies to have positive tax rates, rather than zero tax rates.

4. Exogenous power: “Assuming that group strength is determined exogenously deeply complicate show one

31/n

3. They allow for autocracies to have positive tax rates, rather than zero tax rates.

4. Exogenous power: “Assuming that group strength is determined exogenously deeply complicate show one

31/n

models political conflict. We suggest that it is reasonable to assume that group strength is determined endogenously, and that a group’s likelihood of prevailing in conflict is proportional to the resources it holds.”

For the empirics, I refer you to their book.

Another ...

32/n

For the empirics, I refer you to their book.

Another ...

32/n

paper that is relevant is this one by Freeman and Quinn.

They explore the relevance of financial integration as a moderator of the redistributive logic.

Financial integration manifests itself in three important ways:

· Portfolio diversification such

33/ncambridge.org/core/journals/…

They explore the relevance of financial integration as a moderator of the redistributive logic.

Financial integration manifests itself in three important ways:

· Portfolio diversification such

33/ncambridge.org/core/journals/…

that the wealthy hold greater share of their assets in foreign countries.

· Make-up of the owners of a country’s capital stock change, with more capital held by foreigners

· Capital mobility imposes limit or upper bound on the tax rate the median voter can demand,

34/n

· Make-up of the owners of a country’s capital stock change, with more capital held by foreigners

· Capital mobility imposes limit or upper bound on the tax rate the median voter can demand,

34/n

or, indeed, any government can leverage.

Financial integration raises the probability of democratisation through three mechanisms:

· By allowing elites to evade confiscatory taxation, it lowers the redistributive threat of democratisation. This is the usual logic, first set

35/n

Financial integration raises the probability of democratisation through three mechanisms:

· By allowing elites to evade confiscatory taxation, it lowers the redistributive threat of democratisation. This is the usual logic, first set

35/n

out by Bates and Lien (1985) and, more recently, tested by @boixserra (2003), see below.

· By diffusing the ownership of the country’s capital stock, financial integration reduces the elite’s capacity for collective action against those pushing for democratisation.

36/n

· By diffusing the ownership of the country’s capital stock, financial integration reduces the elite’s capacity for collective action against those pushing for democratisation.

36/n

· Domestic elite has less interest in domestic politics because a greater share of their wealth is held in other countries.

Financial integration implies a lower redistributive threat and, thus, a greater willingness to concede democracy, especially when inequality is high.

37/n

Financial integration implies a lower redistributive threat and, thus, a greater willingness to concede democracy, especially when inequality is high.

37/n

· Effect of inequality on probability of democratisation is moderated by the degree of financial integration, with highly integrated autocracies being more likely to democratise at high levels of inequality than financially closed ones.

· Probability of democratisation

38/n

· Probability of democratisation

38/n

rises with inequality for financially integrated autocracies

· For financially closed autocracies, AR logic holds.

Other contributions challenged AR's points about consolidation, such as Houle's paper. But let me move on to some more fundamental

39/n

cambridge.org/core/journals/…

· For financially closed autocracies, AR logic holds.

Other contributions challenged AR's points about consolidation, such as Houle's paper. But let me move on to some more fundamental

39/n

cambridge.org/core/journals/…

challenges.

@mikealbertus and Menaldo, for instance, argue that 'the key variable that motivates economic elites' willingness to abandon dictatorship and accept democracy is their relative ability to bargain for

40/ncambridge.org/core/journals/…

@mikealbertus and Menaldo, for instance, argue that 'the key variable that motivates economic elites' willingness to abandon dictatorship and accept democracy is their relative ability to bargain for

40/ncambridge.org/core/journals/…

institutions under democracy that can provide a credible commitment to their rights and interests." The idea is that autocratic elites can "bias" democratic transitions in their favour, thus blunting the redistributive threat that democracy poses. The implication is that ...

41/n

41/n

democratisation only leads to redistribution when the elite is weak during transition. "Because this is relatively rare, we argue that democratisation is frequently about allaying fears, and rarely aimed at preventing revolution."

See below for the empirics.

42/n

See below for the empirics.

42/n

Haggard/Kaufman, using their own qualitative dataset covering all democratic transitions between 1980 and

2000, further challenge redistributive accounts in two ways. First, they show that inequality does not significantly predict the occurrence

43/npress.princeton.edu/books/hardcove…

2000, further challenge redistributive accounts in two ways. First, they show that inequality does not significantly predict the occurrence

43/npress.princeton.edu/books/hardcove…

of democratic transitions where the causal mechanisms of redistributive theories are present – namely, mass mobilisation owing to redistributive grievances and elite concessions by virtue of the rising costs of repression. Put simply: where the hypothesised mechanisms are 44/n

present, the theorised reduced-form relationship is not. Second, redistributive conflict was present in roughly 75% of high-inequality transitions (defined as countries in the upper tercile of the Gini coefficient distribution) in their sample – contrary to what 45/n

redistributive accounts predict. I'll conclude that the more recent literature -- particularly the work by @SlaterPolitics/@JosephWongUT and @mkmdem -- point to the importance of the autocratic regime's degree of institutionalisation in the form of strong ruling parties. 46/n

For elites, strong institutionalisation meant that redistributive challenges by the masses were no longer

so threatening. Strong ruling parties, including the PRI in Mexico or the KMT in Taiwan, were often so well-organised that they expected

47/npress.princeton.edu/books/hardcove…

so threatening. Strong ruling parties, including the PRI in Mexico or the KMT in Taiwan, were often so well-organised that they expected

47/npress.princeton.edu/books/hardcove…

to be able to compete successfully in democratic elections and, thus, implement favourable policies under democracy (Riedl et al., 2020; Slater and Wong, 2022). This was partly because of their extensive clientelistic networks and their ability to offer selective 48/n

incentives to their members. Put simply, ruling parties’ ability to successfully address collective action problems – such as running elec. campaigns and engaging in widespread clientelism – meant that conceding democracy was no longer existentially 49/n

press.princeton.edu/books/paperbac…

press.princeton.edu/books/paperbac…

threatening; elites could reasonably expect to hold power from time to time, even in high-inequality contexts.

My reading is the redistributive accounts that AR laid the foundations for shed substantial light on first-wave transitions on democracy, less so for later waves.

50/n

My reading is the redistributive accounts that AR laid the foundations for shed substantial light on first-wave transitions on democracy, less so for later waves.

50/n

Addendum: On evidence that is consistent with redistributive accounts having some explanatory power for first-wave democratisations, see this cool @AJPS_Editor paper by @_adasgupta and @dziblatt onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.11…

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh